I already miss the Chicago Cubs' curse

Sports curses are wonderful — until they're broken

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

At approximately 12:47 a.m. on Nov. 3, 2016, in the city of Cleveland, Ohio, Kris Bryant threw a baseball to Anthony Rizzo.

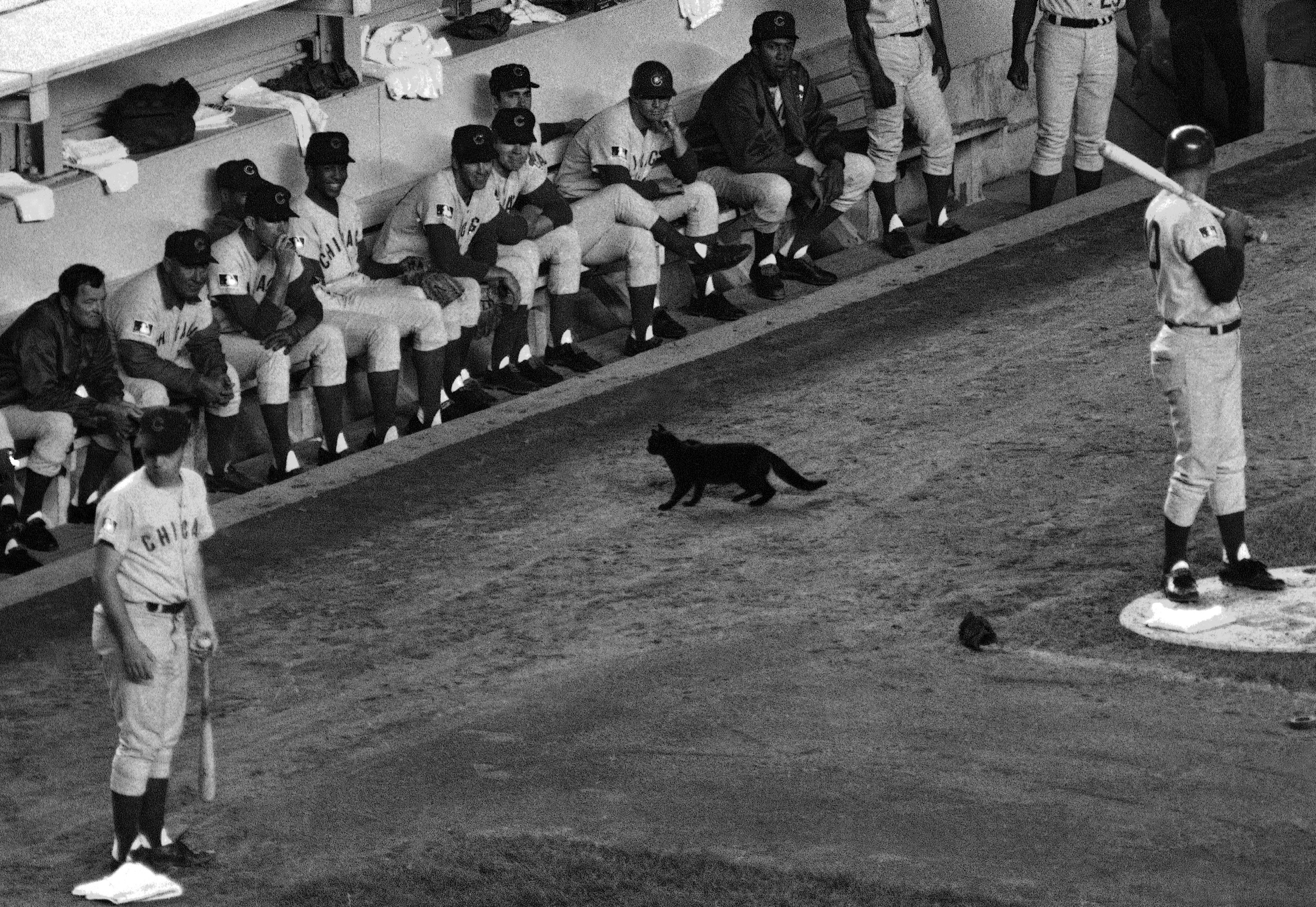

In doing so, Bryant, Rizzo, and the rest of the Chicago Cubs proved that curses don't last forever. They live and then they die. And in this case, the cursed words "them Cubs, they ain't gonna win no more," uttered (allegedly) by a scorned tavern owner in 1945, were suddenly rendered meaningless. The Cubs had not won a National League pennant since the curse was bestowed, and hadn't won a World Series title since 1908, 108 years ago, a year for every stitch that there is in a baseball or feet there are between the foul ball poles at Chicago's Wrigley Field.

The Cubs' World Series victory required no sacrifices or appeals to the ghost of William Sianis (although there was likely plenty of lucky underwear and knocking on wood by Chicago fans). Indeed, despite our mortal efforts, once a curse has been bestowed, there is not much you can do but wait it out. Curses have power — the power to bring entire cities of people together, to give fans something to live for, to draw an audience of 40 million fans and onlookers who just want to witness a sliver of the magic that comes with breaking free of something 108 years in the making.

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But shattering curses has consequences, too. And some of them are bad.

A sports curse is a special anointment, the mark that separates a truly damned franchise from the rest of the teams that are just regularly bad. Curses allow you to believe that there is something divine, or perhaps diabolical, behind your year-after-year disappointment and misery. You and yours alone have been singled out to endure this suffering; you can map your family history by the close calls of the home team and the utterances of "there's always next year."

Naturally, when that (finally!) ends, there is excitement, pyrotechnics, screaming, crying (there is so much crying in baseball), smashed cars, and smashed champagne bottles. But after the broken glass has been swept up the next day, in the early morning afterglow of the celebrations and the drinking and the fireworks, after even the presses have whirred out At Last! in big, bold letters across the top of the local paper, then you, suddenly, are indistinguishable from the rest. Occasional winners. Occasional losers. Curse-less.

Maybe it is the human love of narrative that makes the closure of curses so disappointing. Granted, they are not disappointing from the start — everything to love about baseball is in that electric moment when the ball zips nearly invisible from Bryant's hand to Rizzo's outstretched glove — but the aftermath is shutting a book. At some point, the W will be pulled down, only to be raised again another day. The cycle keeps going on. Winners win and lose, but what makes losers special is that they keep on losing. True losers never win. Until they do. Then they're just like all those other winners.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The Boston Red Sox know something about the mundanity that follows a broken curse. The team also had a World Series title dozens and dozens of years in the making, one that ended a drought of wins that had been strung together every year since 1919, when the team sold Babe Ruth to the New York Yankees. Blood was spilled (down Curt Schilling's ankle) and, the Bambino appeased, the 2004 Red Sox had a victory more than 80 years in the making.

The Red Sox shattered their curse because they were the best team. And then they kept being the best team. And kept being the best team. And when you are the best team for long enough, it gets boring and people stop caring. At a certain point, it can even morph into the opposite of a curse: the St. Louis Cardinals' Devil Magic and the San Francisco Giants' Even Year Magic that you love to root against.

We just so happen to be in a golden era of curse breaking; another team from Cleveland quenched a drought earlier this year. The Cavaliers took down the unstoppable Golden State Warriors and won the first professional sports title in Forest City in half a century. The Cleveland Indians would have been the icing on the cake of the city's broken curse, the one-two punch for long, long suffering fans. Instead, the burden of being the team with the longest time since a World Series win has been passed on to them.

But what, in the end, does a curse even mean? "There are no real curses. We know all that. Right? We know that," Ted Berg writes in his beautiful meditation on superstition, baseball, and being mortal. But that hesitation, the full pause before the question seeking affirmation, that is what baseball is about. The uncertainty. The hope, or possibly dread. The fact that all of this is out of our hands.

Because — at the end of the evening, after the lights are shut off in Cleveland's Progressive Field and everybody flies back to Chicago — there are still 29 teams that didn't win the World Series in 2016. That is where the story begins anew. The hard-luck Mariners who can't even make it to the playoffs, the Texas Rangers and Houston Astros and San Diego Padres, who have all been around since the 1960s and never won a title? Could there be a curse there?

The 2016 Cubs were the best team in baseball, and they deserved their win. But as powerful as this moment is, as strong as this fever, as bright as that grin on Bryant's face, it will fade. It will become one of a dozen other stories of perseverance and achievement and making baseball magic happen.

As for the Indians? They have been without a World Series title for 68 years. And that is a story worth being a part of for as long as it lasts.

Jeva Lange was the executive editor at TheWeek.com. She formerly served as The Week's deputy editor and culture critic. She is also a contributor to Screen Slate, and her writing has appeared in The New York Daily News, The Awl, Vice, and Gothamist, among other publications. Jeva lives in New York City. Follow her on Twitter.