Sex, drugs, and the Summer of Love

Fifty years ago this summer, 75,000 young people flocked to San Francisco to "turn on, tune in, drop out"

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Fifty years ago this summer, 75,000 young people flocked to San Francisco to "turn on, tune in, drop out." Here's everything you need to know:

How did the Summer of Love begin?

In January 1967, San Francisco's nascent hippie community held a "gathering of the tribes" — called the Human Be-In — in the city's Golden Gate Park. At least 20,000 people came, many long-haired and wearing outlandish costumes, to protest a new California law banning the drug LSD, which was freely distributed to the crowd. The beatnik poet Allen Ginsberg led a mass "om" chant, while the LSD guru Timothy Leary (see below) invited the protesters to "turn on, tune in, drop out." Music was provided by local psychedelic rock bands, including the Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane. It was the first of the year's major "happenings," and it generated national publicity. In the spring, a self-appointed hippie "council" invited the youth of America to San Francisco to experience the magic for themselves, during what it called the Summer of Love.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

How many people came?

Starting at spring break, some 75,000 to 100,000 young people converged on the city, inspired by the prospect of a new way of life centered on free love, communal living, and psychedelic drugs. At the epicenter of the counterculture was the down-at-the-heels district of Haight-Ashbury, which had been colonized by a number of alternative communities. Scott McKenzie's ballad "San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair)," a siren call to youth, became an immediate hit on its release in May. Mainstream America watched aghast as TV and newspapers provided daily coverage of the antics of the "flower children." The biggest of the summer's many gatherings was the Monterey Pop Festival in June, the first major festival of its type, where a crowd 60,000-strong witnessed performances by Jimi Hendrix, Otis Redding, Jefferson Airplane, and another local band, Big Brother and the Holding Company — fronted by Janis Joplin.

Why was San Francisco the focal point?

Throughout the 1950s and '60s, San Francisco and the Bay Area attracted artists and those looking for a bohemian lifestyle. Beatnik icons including Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, William Burroughs, and Neal Cassady lived and wrote in the city's North Beach neighborhood. Their works — which sowed the seeds of the hippie revolution — expressed contempt for the cultural norms of 1950s America and encouraged spiritual questing, sexual liberation, experimentation with drugs, and a rejection of materialism. There was also a large, radical student community in the area, based around its various universities and colleges.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

And who were 'the hippies'?

They were essentially an assortment of like-minded "tribes" based in the Bay Area at the time. Ken Kesey's Merry Pranksters toured in a graffiti-covered school bus driven by Cassady, and offered free "Acid Tests" — with LSD-laced Kool-Aid, and diplomas for those who "passed." In Haight-Ashbury, there were groups such as the Family Dog, who lived communally and did much to popularize the fashion for long hair and "old-timey" clothes, and the Diggers, "community anarchists" who sought to create a society free of money. The San Francisco Chronicle columnist Herb Caen dubbed these young bohemians "hippies" — a slang term for someone who is "hip," or in the know.

Were the hippies political?

To an extent. The period was politically charged: The Vietnam War was raging, and the civil rights movement had given way to inner-city race riots. But among the hippies, political aims were mixed with broader lifestyle protests. Peter Coyote, co-leader of the Diggers, later recalled that he "was interested in two things: overthrowing the government and f---ing. They went together seamlessly." Free love, abetted by the growing availability of the contraceptive pill, was a central tenet. In July 1967, Time magazine attempted to describe the hippie philosophy: "Do your own thing, wherever you have to do it and whenever you want. Drop out. Blow the mind of every straight person you can reach. Turn them on, if not to drugs, then to beauty, love, honesty, fun."

How did the summer end?

By the time the summer influx was in full swing, the city's services were struggling to cope, and the streets were full of teenagers with no money, no food, and no plans. By July, crime and violence were soaring, and there were frequent clashes between the hippies and police. In the fall, most of the young people went back to college or returned home. The Summer of Love, said Joel Selvin, another Chronicle columnist, was a "utopian movement" that was "undermined by the reality of the human species."

Did hippies change the world?

In the short term, no. But there's no denying the transformative effect of the Summer of Love on mainstream society. It left an indelible imprint on popular music, how people dressed and wore their hair, and, more generally, people's perspectives. Hippie enthusiasms have spread out across the Western world, including drug use, sexual openness, blue jeans, environmentalism, yoga and meditation, organic food, and vegetarian diets. What was once the counterculture is now part of the culture. William Hedgepeth, who as a young reporter went undercover to write about the summer's events, explained, "Consciousness is irreversible. I never wore a suit again."

LSD and the doors of perception

In 1962, a charismatic Harvard psychologist named Timothy Leary became fascinated by a new drug called lysergic acid diethylamide, or LSD. He believed it to be the key to a new dimension — and that it was designed to reveal to us the true nature of the universe. Leary left Harvard when a collaborator was fired for giving LSD to undergraduates, and began a campaign to introduce intellectuals and artists to psychedelic drugs. President Richard Nixon later labeled Leary "the most dangerous man in America." LSD, first synthesized in Switzerland in 1938, causes hallucinations and altered perceptions, but can also trigger "bad trips" filled with anxiety, paranoia, and delusions. Nonetheless, Leary, the writer Ken Kesey, and other enthusiastic LSD evangelists insisted the drug provided a shortcut to enlightenment. "With LSD, we experienced what it took Tibetan monks 20 years to obtain," said one member of the Family Dog commune, "yet we got there in 20 minutes."

-

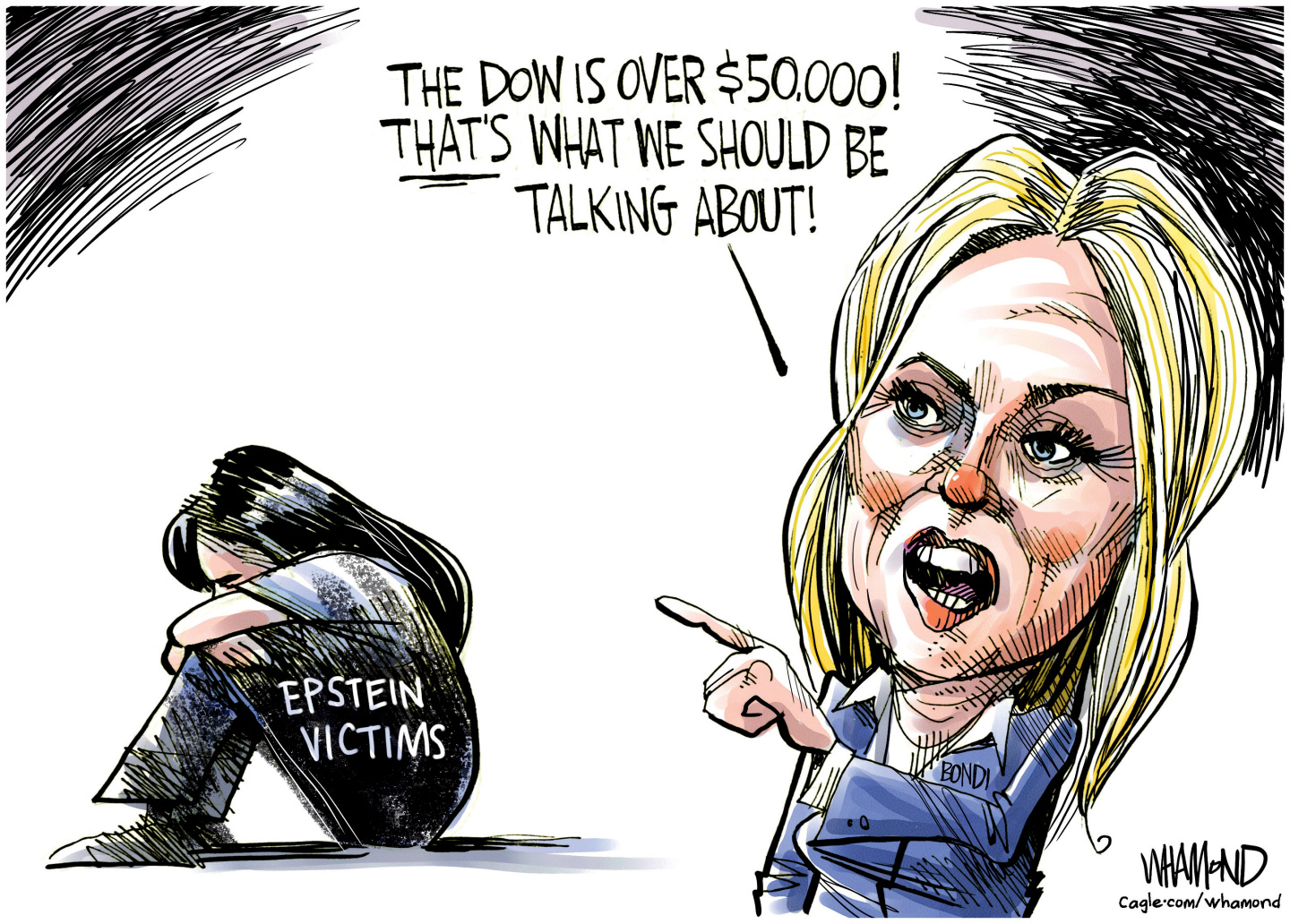

Political cartoons for February 12

Political cartoons for February 12Cartoons Thursday's political cartoons include a Pam Bondi performance, Ghislaine Maxwell on tour, and ICE detention facilities

-

Arcadia: Tom Stoppard’s ‘masterpiece’ makes a ‘triumphant’ return

Arcadia: Tom Stoppard’s ‘masterpiece’ makes a ‘triumphant’ returnThe Week Recommends Carrie Cracknell’s revival at the Old Vic ‘grips like a thriller’

-

My Father’s Shadow: a ‘magically nimble’ film

My Father’s Shadow: a ‘magically nimble’ filmThe Week Recommends Akinola Davies Jr’s touching and ‘tender’ tale of two brothers in 1990s Nigeria

-

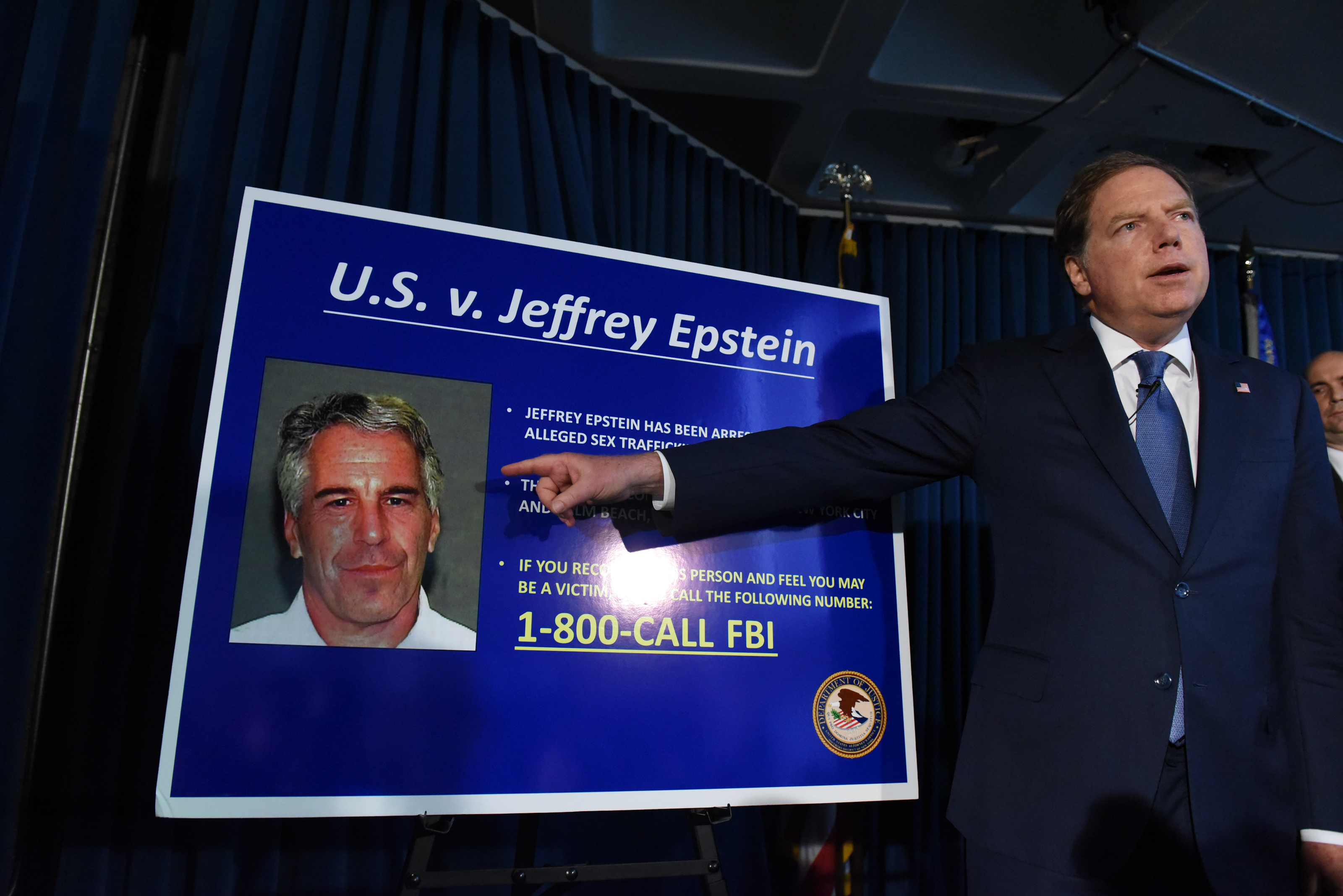

7 lingering questions about Jeffrey Epstein's death

7 lingering questions about Jeffrey Epstein's deathThe Explainer Truth can be as strange as conspiracy theories

-

3 things everyone is getting wrong about the El Paso-Dayton shootings

3 things everyone is getting wrong about the El Paso-Dayton shootingsThe Explainer Mental illness is a red herring — but so is Trump

-

Is it dangerous to lionize the heroes of school shootings?

Is it dangerous to lionize the heroes of school shootings?The Explainer Honoring the children who die saving classmates is laudable — but we should tread carefully

-

The fear we all live with

The fear we all live withThe Explainer What mass shootings have done to the American psyche

-

The sick phenomenon of school shooting contagion

The sick phenomenon of school shooting contagionThe Explainer Mass shootings can spread like a disease, with each massacre inspiring new rampages. Can the cycle of violence be stopped?

-

Why the Parkland conspiracy theories are different

Why the Parkland conspiracy theories are differentThe Explainer They aren't an attempt to make crazy sense of a senseless tragedy. They are a way of saying to the tragedy's victims and survivors: You aren't even worth arguing with.

-

What we know about gun violence may surprise you

What we know about gun violence may surprise youThe Explainer Contradictions abound

-

The struggle over the Temple Mount

The struggle over the Temple MountThe Explainer Rumors that Israel will take over Temple Mount have infuriated Palestinians, fueling a new wave of violence