3 things everyone is getting wrong about the El Paso-Dayton shootings

Mental illness is a red herring — but so is Trump

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Mass shootings happen so regularly in America — and the stories of carnage when they do are so horrifying — that it's perfectly understandable that each new event would inspire demands for new laws and regulations based on instantaneous, impassioned analysis. The instinct to "do something" to stop the suffering and fear, and prevent yet another trauma, is very powerful. But that doesn't mean that these initial thoughts make a lot of sense.

Three ideas floated frequently in the days since the dual massacres in El Paso, Texas, and Dayton, Ohio, are especially ill-considered.

1. Mass shootings are a symptom of Trump's embrace of white nationalism. Heard repeatedly in the hours following the bloodbath in El Paso — both because the shooter apparently traveled hundreds of miles to the southern border to fight back against "the Hispanic invasion of Texas," and he appears to have written a xenophobic manifesto that he posted just before commencing his attack — this analysis seeks to draw a direct line between the massacre and President Trump's incendiary language about immigrants. In this telling, the shooting was a consummate political act linked directly to the white nationalist movement that Trump leads and encourages at his rallies and in his tweets. It was terrorism, not the act of a random psychopath.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

That may well be true in this particular case, just as the Pittsburgh synagogue shooting last October was obviously an act of bloodthirsty anti-Semitism, and the Charleston church shooting in June 2015 was committed by an avowed white supremacist seeking to kill as many African Americans as possible, and the Orlando nightclub shooting from June 2016 appears to have been motivated by a combination of Islamist ideology and virulent homophobia.

If we define terrorism to mean politically motivated violence, then all of these events could be described as acts of terror.

But what about all the other mass shootings — the ones in which the perpetrator repeatedly pulls the trigger for no discernable political reason at all? This appears to include the Dayton shooting that took place less than 24 hours after the El Paso massacre. And the Stoneman Douglas High School shooting in Parkland, Florida, from February 2018. And the 2012 attack at a movie theater in Aurora, Colorado. And the deadliest mass shooting in American history — in which a man murdered 58 and injured 527 when he opened fire on a crowd at a concert from the window of a hotel in Las Vegas in October 2017. And the distinctively heart-wrenching assault at Sandy Hook Elementary School in December 2012, when 26 were killed, most of them children between 6 and 7 years old.

In all of those cases, and many more, politics was beside the point. The shooters were sociopaths who wanted to kill as many people as possible, full stop. That's certainly terrifying, but it isn't terrorism. We even run a risk in placing the political motives of the El Paso shooter in a tidy political box, since his alleged white supremacist manifesto included passages that expressed the desire to make the American way of life more environmentally "sustainable."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The president's rhetoric is certainly poisonous, and it might provide a motive to a homicidal maniac looking for an excuse to justify acting out in murderous rage. But such acts happened before Trump, and they will unfortunately continue after Trump. We should resist the urge to make everything about the president. America's problems go far deeper.

2. Banning assault weapons and imposing background checks will fix the problem. If only this were true. Yes, we should definitely pass tougher gun control measures. Even before the savagery of this past weekend, a recent poll showed overwhelming (89 percent) support for background checks and strong majority support (57 percent) for a ban on assault rifles, the kind of weapons most often used in such attacks.

But we shouldn't for a minute think this will stop the carnage. It might, at most, somewhat lower the death toll at such events. The combination of the Second Amendment and America's gun culture have led there to be several hundred million guns in circulation. This means that, as I wrote shortly after the Parkland shooting, someone hellbent on mass murder will always be able to find a gun to help him accomplish his goal.

If AR-15s were banned, the Parkland shooting suspect (who apparently purchased his weapon legally) would have needed to use … one of the countless other guns on the market, including dozens of semiautomatic pistols and rifles. Maybe in that case he would have succeeded in killing 13 people instead of 17. For the four spared lives, and their loved ones, this would be all the difference in the world. But the country would still be mourning a mass shooting today, liberals would still be railing against the NRA and calling for more gun control, and the president would still have given a blandly consoling speech. [The Week]

That remains true today, and it will remain true until the country stops producing so many men (yes, it is almost always men) who are led to sow death and destruction.

3. The "real" problem is mental illness. This has become a post-shooting talking point in recent years, and there's considerable truth to it. But it is at once too narrow and too broad. It's too narrow because it gives pro-gun politicians and voters a convenient way of skirting the call for stronger gun control measures. As David Frum has powerfully and persuasively argued, all countries have mentally ill citizens, yet only America has near-daily mass shootings. That's because in this country those suffering from violent forms of psychopathology have relatively easy access to an incredibly wide range of weapons with which to enact their murderous fantasies. That means that talking about mental illness without also discussing guns is an obvious dodge.

But the invocation of mental illness is also too broad because the overwhelming majority of people suffering from such illness — from anxiety and depression to PTSD and beyond — are not potential mass murders, or especially violent in any way. Mass shootings are the result of an extremely specific form of mental illness, one in which, in most cases, anger and resentment builds to enormous heights, utterly warping moral judgment, and then intertwines with an almost total lack of empathy to produce a drive toward death.

Why the U.S. appears to produce so many men who exhibit this specific, extraordinarily dangerous form of mental illness is a very important question, though one unlikely to yield a clear-cut answer, let alone one that lends itself to an obvious public-policy solution — not least because such men can also be found in many other places in the world. This is a human problem first and an American problem second.

The honest and ugly truth is that Americans inhabit a country in which a small number of madmen have relatively easy access to enormously powerful weapons. The result is a regular drumbeat of death. And we really know of no way to stop it.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

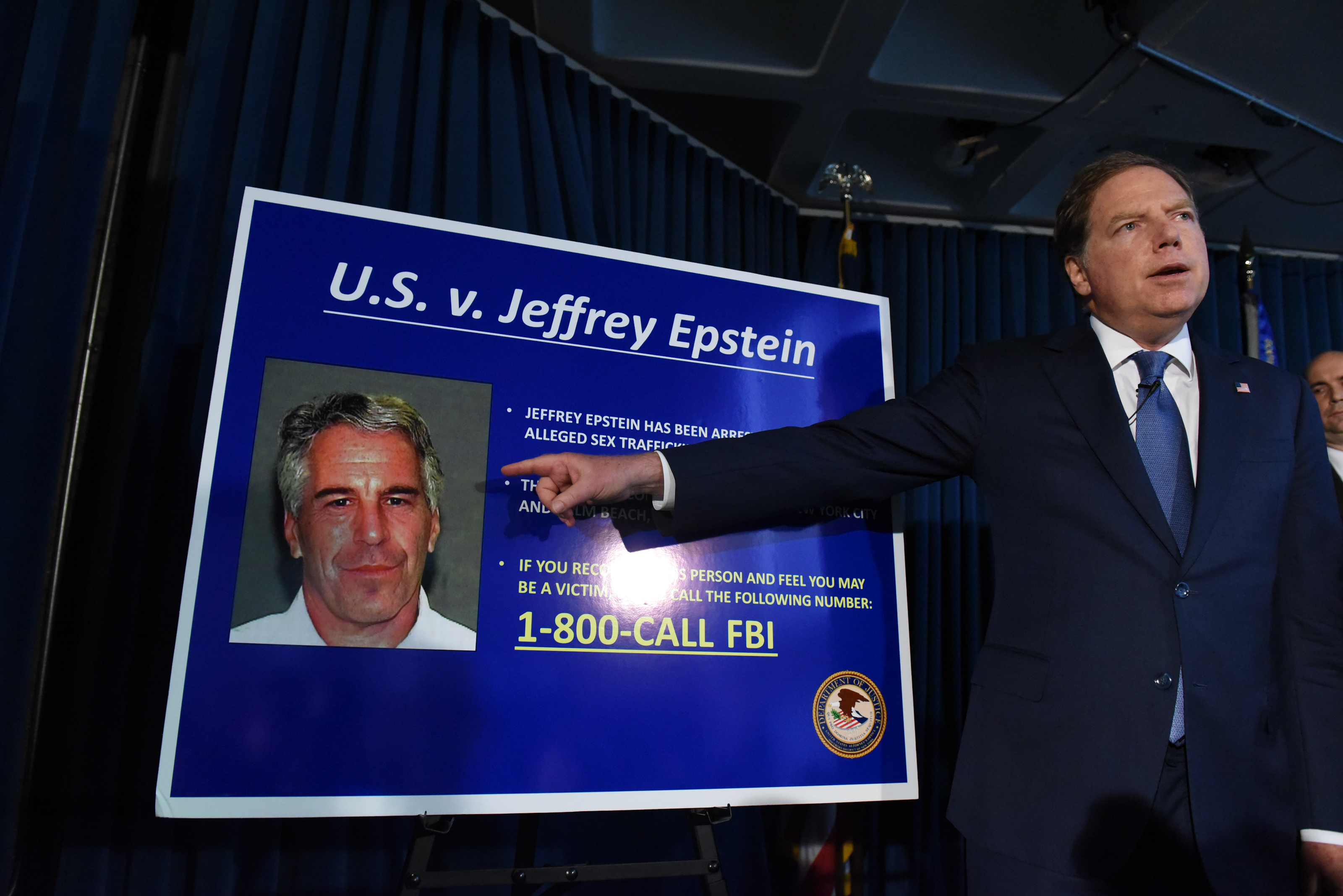

7 lingering questions about Jeffrey Epstein's death

7 lingering questions about Jeffrey Epstein's deathThe Explainer Truth can be as strange as conspiracy theories

-

Is it dangerous to lionize the heroes of school shootings?

Is it dangerous to lionize the heroes of school shootings?The Explainer Honoring the children who die saving classmates is laudable — but we should tread carefully

-

The fear we all live with

The fear we all live withThe Explainer What mass shootings have done to the American psyche

-

The sick phenomenon of school shooting contagion

The sick phenomenon of school shooting contagionThe Explainer Mass shootings can spread like a disease, with each massacre inspiring new rampages. Can the cycle of violence be stopped?

-

Why the Parkland conspiracy theories are different

Why the Parkland conspiracy theories are differentThe Explainer They aren't an attempt to make crazy sense of a senseless tragedy. They are a way of saying to the tragedy's victims and survivors: You aren't even worth arguing with.

-

Sex, drugs, and the Summer of Love

Sex, drugs, and the Summer of LoveThe Explainer Fifty years ago this summer, 75,000 young people flocked to San Francisco to "turn on, tune in, drop out"

-

What we know about gun violence may surprise you

What we know about gun violence may surprise youThe Explainer Contradictions abound

-

The struggle over the Temple Mount

The struggle over the Temple MountThe Explainer Rumors that Israel will take over Temple Mount have infuriated Palestinians, fueling a new wave of violence