The policy experiment that might just save Puerto Rico

It's time to test a "job guarantee" on the island

Puerto Rico is in a horrible mess. Its economy was already reeling from a decade of recession and debt crisis when Hurricane Maria hit in late September and further demolished the island.

But desperate times are also opportunities to try something new. And there's a radical idea floating around that could be just what Puerto Rico needs.

It's called a job guarantee.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Basically, it's a public option for employment. If an adult wants work and can't find a decent job from private employers, the government will find them something productive to do in their community. They'll be paid a living wage, along with health coverage, paid leave, retirement benefits, and so forth.

While a job guarantee has never been tried before, the idea has enjoyed a burst of attention recently, as the U.S. continues to grapple with the long aftermath of the Great Recession. Economists from the Obama White House, the Clinton White House, and even the Trump White House have endorsed the idea or something similar. The Center for American Progress, a think tank closely associated with the Democratic Party, recently put out a proposal for a "light" version of a job guarantee. I even wrote a long piece on the idea myself earlier this year.

But for many, a job guarantee is still rather "out there." What we need is a test run.

Enter Puerto Rico.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Setting up an ambitious plan on an island of 3.4 million would be much easier than in a nation of 320 million. It would be an opportunity to figure out the best practices and design for the program, discover problems early, and answer looming questions about the proposal.

Puerto Rico also has enormous amounts of work that needs doing, but isn't getting done. As of mid-November, over half the island still didn't have electricity, and 17 percent still didn't have access to drinking water. Its power grid needs to be rebuilt; its roads and bridges need to be cleaned up and repaired; its health-care system needs a lot of help. The island's poverty rate was over 44 percent before the hurricane, and jumped to nearly 53 percent afterwards.

Plenty of Puerto Ricans are available to help. The island's unemployment rate is over 10 percent. Its labor force participation rate was already quite low before the 2008 crisis, at 48 percent. Now, it's 40 percent.

Neoliberal government policy and the private markets have failed the island. Years of mismanagement by the federal government, not just the island itself, undercut job creation and pitched Puerto Rico into debt and recession. To pay off its creditors, the island is being forced to extract cash from its population and massively cut public investment. Puerto Ricans are being bled of the money they would otherwise use to buy goods and services in the island's economy. Businesses are folding because they don't have enough sales, the jobs supply is collapsing, wages are falling, and Puerto Ricans are leaving for the mainland in record numbers. All with no end in sight.

But a job guarantee would revitalize the island's economy. The incomes paid to people on the program would translate into fresh consumer spending, leading to job growth in the private sector again. Fewer households would be underwater or likely to default, and Puerto Rico's tax base would recover. Eventually, there'd be enough private jobs offering better pay and benefits that the job guarantee rolls would shrink.

Now, regardless of how the administration of the program is designed, the money for a Puerto Rican jobs guarantee must come exclusively from the federal government. That's because of the latter's unique fiscal and monetary powers to spend during crisis.

So how much would it cost?

Let's say we tried a Puerto Rico-sized version of the proposal in my earlier piece, which suggested a wage of $25,000, plus benefits. If we wanted to solve Puerto Rico's unemployment problem and push its labor force participation back to 48 percent, that would cost roughly $13 billion annually. If we wanted to push labor force participation higher, say to the 67 percent that America as a whole enjoyed in its best recent moments, that would cost roughly $33 billion a year.

Now, Puerto Rico's median household wage was only $18,600 in 2015 — compared to an overall American median of $55,700. Some might argue the job guarantee shouldn't pay more than that median. I don't necessarily agree, but let's say we decided to play it conservative and set the Puerto Rico job guarantee wage at $15,000 instead. That would reduce the cost by around one fourth.

Finally, remember the job guarantee is designed to naturally shrink as it repairs the overall economy. Over the long term, the program would stabilize at a far smaller annual cost.

The island needs other forms of help too, like forgiveness of its public debt and some sort of write-down program for private mortgage debt. And while my numbers do include money for capital costs, there'd likely be other big upfront costs for all the supplies needed to repair Hurricane Maria's destruction. But they'd be one-time upfront costs.

At any rate, $13 billion or $33 billion a year? They're both chump change to the federal government; a fraction of a percent of its annual spending. For that chump change, we could fund an experiment that could resurrect Puerto Rico's economy and help millions of people. And if it works, we'd have a model for repairing the social fabric of the whole country.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

Which way will Trump go on Iran?

Which way will Trump go on Iran?Today’s Big Question Diplomatic talks set to be held in Turkey on Friday, but failure to reach an agreement could have ‘terrible’ global ramifications

-

High Court action over Cape Verde tourist deaths

High Court action over Cape Verde tourist deathsThe Explainer Holidaymakers sue TUI after gastric illness outbreaks linked to six British deaths

-

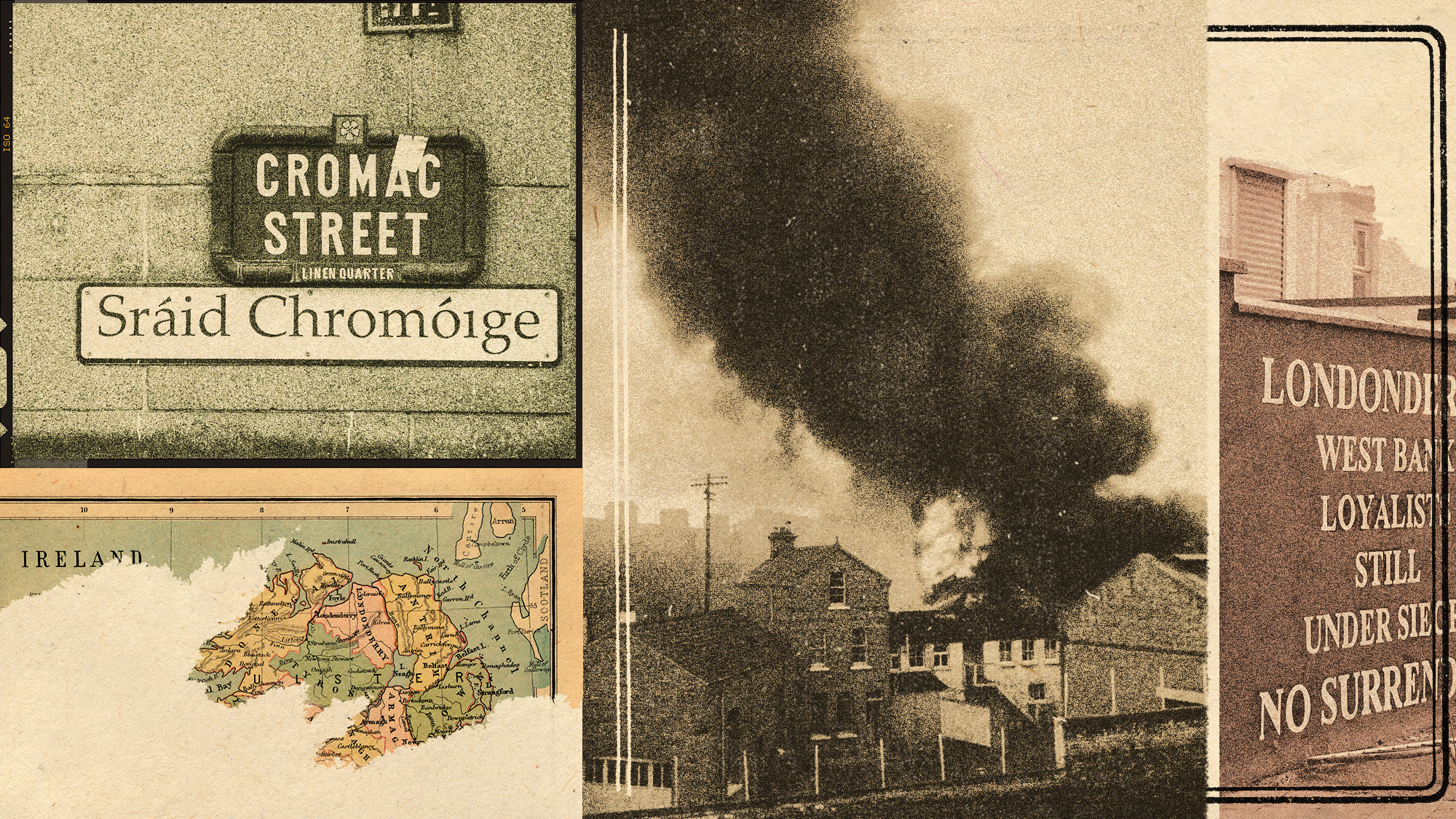

The battle over the Irish language in Northern Ireland

The battle over the Irish language in Northern IrelandUnder the Radar Popularity is soaring across Northern Ireland, but dual-language sign policies agitate division as unionists accuse nationalists of cultural erosion