3.8 percent unemployment just ain't what it used to be

It's only gotten this low twice in the last 50 years — but the economy was far, far healthier back then

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

This past Friday, the U.S. unemployment rate fell to an astounding 3.8 percent. For a little perspective, it's only gotten that low twice in the last 50 years: once in 2000, and also in the period from 1968 to 1970.

But if you suggested to most Americans that the economy is just as healthy today as it was in 2000 or 1968, they'd probably laugh in your face.

Wage growth in 1968 was significantly higher than it was in 2000. And in 2000, it was significantly higher than it is today, too. That relationship holds even after you factor out inflation. Recoveries from recessions have gotten longer and longer. Inequality is worse: The top 1 percent gobbled up around 10 percent of all national income in 1968, 15 percent in 2000, and 20 percent today. Costs of necessities have also risen, leaving the median household budget with less money today than in 1972.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What happened?

Well, first off, a big part of the problem is that 3.8 percent unemployment is so rare.

One of the big drivers of wage growth is labor scarcity. When businesses can't just hire jobless people, they have to hike wage offers to lure workers away from competitors. Periods of significant labor scarcity also reduce inequality, since wages tend to grow fastest for the poorest workers.

But in between the brief triumphal moments of low unemployment, America has gone through long periods of much higher unemployment. Those stretches destroyed Americans' incomes and livelihoods. And the brief bursts of full employment we have enjoyed in the last half century weren't nearly enough to repair the damage.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Next, when we say unemployment is such-and-such percent, what we mean is a percent of the labor force, not the entire U.S. population. So who's in the labor force? Government statistics say it's anyone who has a job or has looked for one in the last month.

Now, the labor force participation rate did indeed rise from 60 percent in 1968 to 67 percent in 2000, but it's a complicated picture; much of the rise was due to the massive cultural shift as many more women entered the workforce. What's more important for this comparison is the difference in labor force participation between 2000 and 2018 — both years that came after that cultural shift was largely complete. And by 2018, labor force participation had fallen from 67 percent to just under 63 percent.

That 4 percentage-point drop can't be explained just by the growing share of the population that's retired, either. The crisis of 2008 decimated the workforce, and led to a huge increase in long-term unemployment. Unlike 2000, we now have a huge population of "shadow unemployed" — jobless people who could be working and want to work, but who aren't picked by the official unemployment rate.

Besides tight labor markets, another thing that boosts wage growth and reduces inequality is unions. As the old worker anthem "Solidarity Forever" points out, there's nothing weaker than a lone individual worker. They have no leverage over their employers, who own the business and the capital, and enjoy all the social and economic power. But as an organized whole, workers can wield enormous power to demand a bigger cut of the wealth their companies create — and to threaten work stoppages and shutdowns if those demands aren't met.

Back in 1968, no less than 30 percent of American workers belonged to a union. By 2000, that had fallen to around 10 percent. It's even lower today.

Without unions, it's a lot harder to make sure a growing economy shares the wealth it creates in a broad and egalitarian manner.

Yet another thing that's changed is market concentration.

We all understand why it's bad when companies that sell goods and services become monopolies: They can jack up prices and gouge the rest of us without having to worry about competitive pressure. But the same principle applies in reverse if there's only one company in a market buying stuff — a situation referred to as "monopsony." Companies that have a monopsony can drive down the price of what they're buying without facing any counter-pressure. And that applies just as much when the thing they're buying is Americans' labor.

A recent study looked at how many employers there are in American labor markets from 2010 to 2013. The researchers found that, in most local labor markets, monopsony is pervasive. Only in major cities are there adequate numbers of employers competing for workers' labor.

It's a lot harder to extrapolate this data backwards. But there's circumstantial evidence the problem is much worse now than in 2000 or 1968.

For instance, in 1994, the revenue of the 500 largest companies in the country accounted for 58 percent of the economy. By 2013, it was 73 percent.

Antitrust enforcement has also changed drastically. Before the 1980s, regulators and judges applied much stricter standards to monopoly and monopsony. They would break up a company for gobbling up just 7 percent of its respective market. Today, policymakers tolerate companies ruling 40 percent of their markets or more without complaint.

There were other changes, too, like the increase in workers who are considered independent contractors. That's yet another change that gives employers more leverage to drive down pay and cut benefits.

Over the last 50 years, American workers were hit with a series of blows that just left them ever worse off. In fact, when you dig below the surface, even the late 1990s boom doesn't look so good: It wasn't driven by a basic shift in worker fortunes and power, but by an unsustainable stock bubble. The economy has been rotting almost continuously since the late 1960s.

As a result, 3.8 percent unemployment just ain't what it used to be.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies end

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies endFeature 1.4 million people have dropped coverage

-

Anthropic: AI triggers the ‘SaaSpocalypse’

Anthropic: AI triggers the ‘SaaSpocalypse’Feature A grim reaper for software services?

-

NIH director Bhattacharya tapped as acting CDC head

NIH director Bhattacharya tapped as acting CDC headSpeed Read Jay Bhattacharya, a critic of the CDC’s Covid-19 response, will now lead the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

-

Unemployment rate ticks up amid fall job losses

Unemployment rate ticks up amid fall job lossesSpeed Read Data released by the Commerce Department indicates ‘one of the weakest American labor markets in years’

-

Is the UK headed for recession?

Is the UK headed for recession?Today’s Big Question Sluggish growth and rising unemployment are ringing alarm bells for economists

-

Are we getting a 'hard landing' after all?

Are we getting a 'hard landing' after all?Today's Big Question Signs of economic slowdown raise concerns 'soft landing' declarations were premature

-

What new president Bola Tinubu means for Nigeria

What new president Bola Tinubu means for Nigeriafeature Many question whether 70-year-old will be able to revive ailing economy, heal divisions and provide security

-

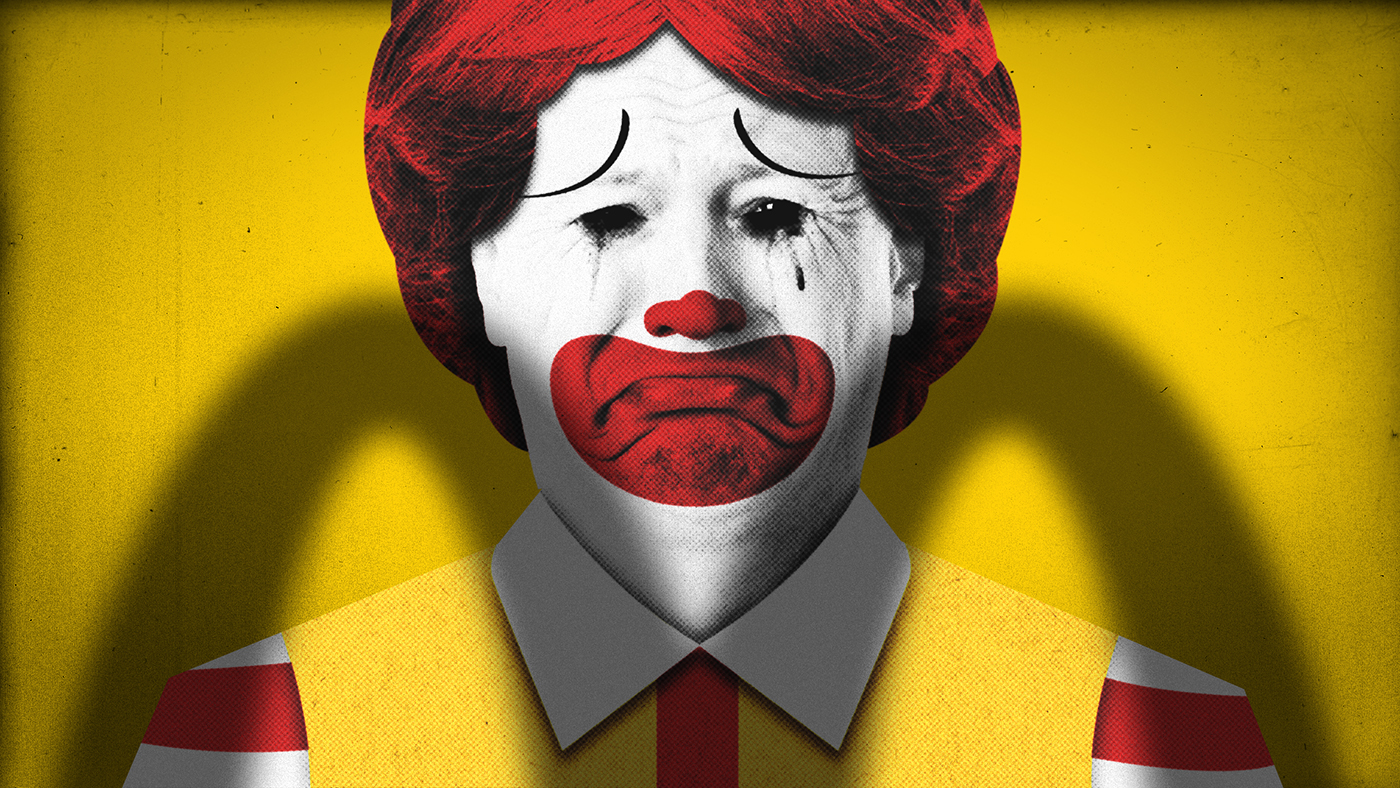

What’s happening at McDonald’s?

What’s happening at McDonald’s?Under the Radar Fast-food chain closed US offices and told staff to work from home while it announces job cuts

-

UK avoids recession - but will anyone notice?

UK avoids recession - but will anyone notice?Today's Big Question Think tank says 2023 ‘will feel like a recession for many, regardless of the data’

-

Is 2023 the year of the worker?

Is 2023 the year of the worker?Speed Read

-

Britain’s missing workers

Britain’s missing workersIn Depth A large number of working-aged people are ‘economically inactive’ and putting a strain on the UK workforce