Why rejecting birth control can be an empowering feminist choice

Confessions on my organic-sex life

I'm not by nature an exhibitionist, but we all have our moments of temptation. Mine often come in elevators, when I'm momentarily cloistered in close quarters with my four young boys and some man. It's crowded, so he is literally backed in a corner. I see him glancing back and forth between the children and me, his thoughts as clear as a baby's bottle. Can they really all be hers? Holy cow.

In my fantasy, I address him casually. "Hey, Mr. Staring Guy," I say. "Have you had sex four times in your life? That's great. Me too!"

I don't actually say this, because a lady doesn't kiss and tell, even when the evidence is rummaging through her coat pockets and tugging at both sleeves. It's fun to imagine though, and since my fifth is expected at the end of this year, it should soon be possible to shock without speaking. I'm looking forward to some sizzling months of scaring strangers with my shameless fecundity. Four boys, and she's even having another one? Who does that?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The short answer is: a Catholic. I'm one of those crazy orthodox ones who shuns artificial contraceptives.

When my husband and I plunged into this lifestyle a decade ago, we were recent Catholic converts, and perhaps not fully aware that we were flinging ourselves into a chasm of religious zealotry. I'd read the Catechism, and a collection of important papal encyclicals. It seemed like this was how Catholics did things. Naturally, in the intervening years I've been acquainted with the reality that I am a nut, enslaved to patriarchy and probably dwelling somewhere in the low country between Michael Houellebecq's France and Margaret Atwood's Republic of Gilead. That's a little startling, but I soldier on anyway. For one thing, I like to finish what I start. Also, I'm actually pretty happy with the organic-sex lifestyle. It's a little demanding on certain fronts, but it makes for a very meaningful life, and one that is in some respects especially good for women.

You can back away slowly at this point, but as you're retreating, let me ask one question. Isn't it normally better to respect the natural rhythms of organic things? My liberal friends certainly seem to think so if the subject is organic farming, or the restoration of natural ecosystems. They're enthused about breastfeeding and free bleeding, along with cleansing fasts and raw food diets. You can even try the paleo diet if you wish to reboot prehistoric organic rhythms. Natural is good!

Now, I can understand why the Church's teaching on birth control was explosively controversial 50 years ago. Those were the days when people yearned to eat like astronauts, and made sacrifices to afford the newest artificial formulas for their babies. Today though, the world seems to have rediscovered the wisdom of respecting nature. Why is human reproduction one of the only things we don't want au natural?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Of course, I know the answer to that. It's because most of us don't want 15 children (or even five). Beyond that, many see fertility, with its grotesquely inegalitarian division of labor, as a major reason why women historically have so often been relegated to a disadvantaged social class. This is a major theme of feminist theory, perhaps most eloquently articulated by the French writer Simone de Beauvoir, who argued that woman (being physically weaker and uniquely capable of childbearing) has been regularly cast in the role of the "other," a mere complement to transcendent man. I find some portions of Beauvoir's work quite compelling, especially because it does seem that women's social contributions are more easily taken for granted when they are supposed to be "assigned by nature." Men make great contributions too, but theirs seem more voluntary and so tend to be more rewarded. It seems obvious that there is a pervasive tendency across history to underestimate women's real capacity for virtue and rarified excellence. I am glad that feminism has helped to rectify those errors, even as I lament many of her other fruits.

Now though, I think women are in a position to demand more. We shouldn't have to choose between self-sterilization and a marginal social status as "the second sex." We should be able to embrace our physiology in all its aspects, while demanding that men do the same. The truth is that women do pay a price for the suppression of natural fertility. Part of that is physiological, while other consequences spring from the fact that women have narrower windows of time in which to realize the good of parenthood. Then there are a host of cultural consequences. Just over the past few years, we have several times been shocked by revelations of appalling sexual exploitation, on college campuses and in workplaces. Obviously nothing justifies sexual predation, but it's undoubtedly easier for men to treat women as sex toys when pregnancy is effectively removed from the picture. Feminists have amply proven that women are capable of great strength, independence, and achievement, but we still have some unique vulnerabilities relating to sex. The organic-sex lifestyle respects that. By treating fertility as a natural aspect of womanhood, it motivates men to consider carefully whether they're truly ready for sexual intimacy.

This has been a strange month for Catholics. We have just celebrated the 50-year anniversary of Humanae Vitae, the controversial encyclical that formally declared artificial contraceptives to be unethical. At the same time, the Church has been rocked by yet another sex scandal involving a predatory prelate and a cowardly coverup. In light of all this, I can see why Catholics like myself look to many of our friends like anachronistic chumps. Our established ecclesial authorities are cavorting off to their beach houses for Hefneresque debauchery, but here we are, still doing our LaMaze exercises and obediently funneling our excess income into diapers and parochial school tuition. Only religion could instill that level of slavish obedience, right? No infomercial or fake news campaign could possibly be so effective.

I understand that reaction. Of course, there are sacrifices. Compared to couples of equivalent education (we both hold Ivy League Ph.D.s), my husband and I are perhaps less wealthy than we might be, and our lives are packed with Power Rangers, Happy Meals, and endless school events. I'm not so naïve as to expect that this lifestyle will sweep the nation anytime soon. Even so, I think organic-sex living could be good for America, even if it's embraced by just a few. Compare us to pacifists, vegetarians, or other minority groups who make relatively few converts, but still force all the rest of us to think more deeply about our choices and commitments. Why do I live like this? Do things have to be this way, or how might they be different?

I'm not an exhibitionist, but I do like to think of myself as part of a creative minority. We can create in more ways than one.

Rachel Lu is a writer based in Roseville, Minnesota. Her work has appeared in many publications, including National Review, The American Conservative, America Magazine, and The Federalist. She previously worked as an academic philosopher, and is a Robert Novak Journalism Fellow.

-

High Court action over Cape Verde tourist deaths

High Court action over Cape Verde tourist deathsThe Explainer Holidaymakers sue TUI after gastric illness outbreaks linked to six British deaths

-

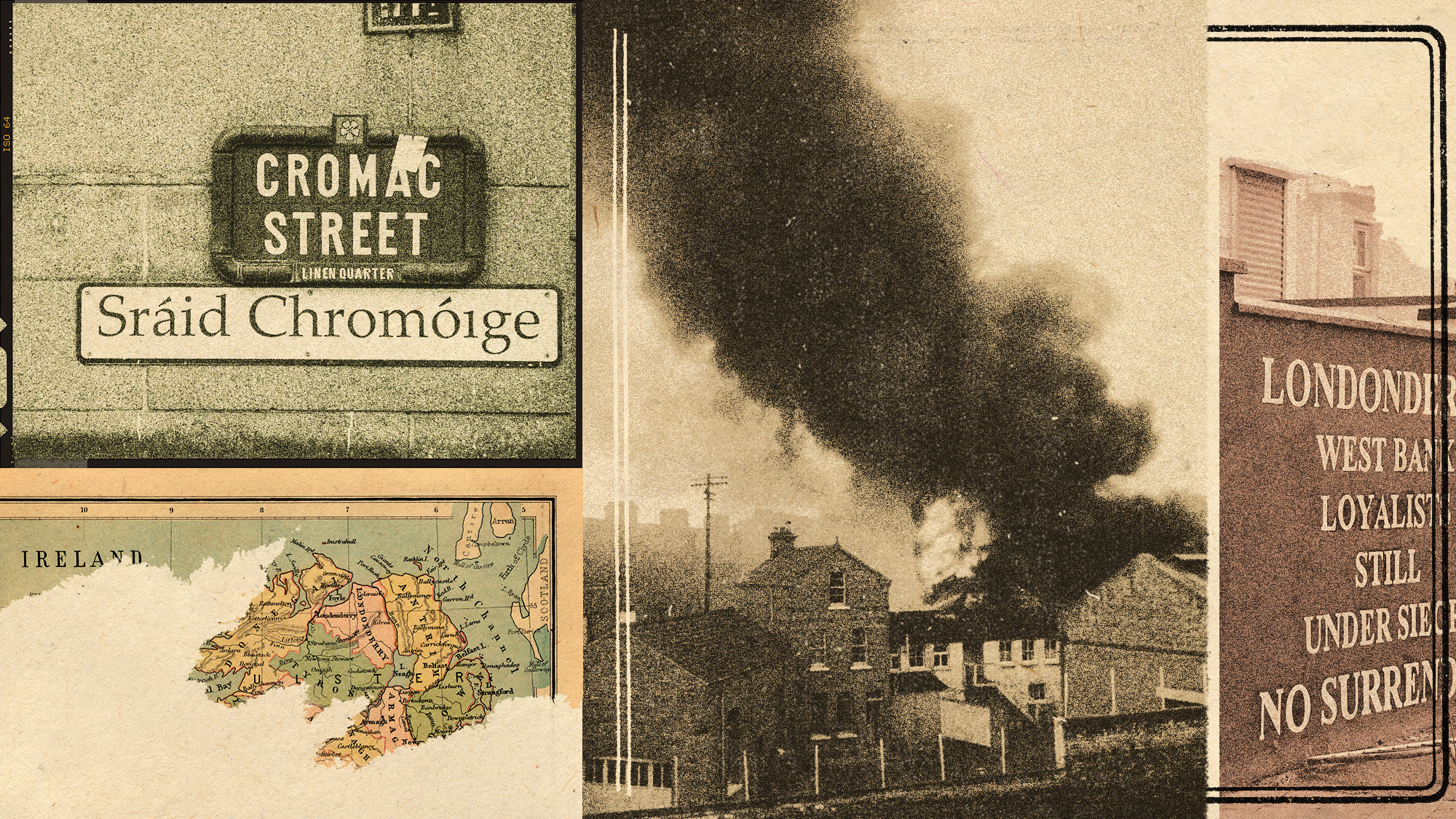

The battle over the Irish language in Northern Ireland

The battle over the Irish language in Northern IrelandUnder the Radar Popularity is soaring across Northern Ireland, but dual-language sign policies agitate division as unionists accuse nationalists of cultural erosion

-

Villa Treville Positano: a glamorous sanctuary on the Amalfi Coast

Villa Treville Positano: a glamorous sanctuary on the Amalfi CoastThe Week Recommends Franco Zeffirelli’s former private estate is now one of Italy’s most exclusive hotels