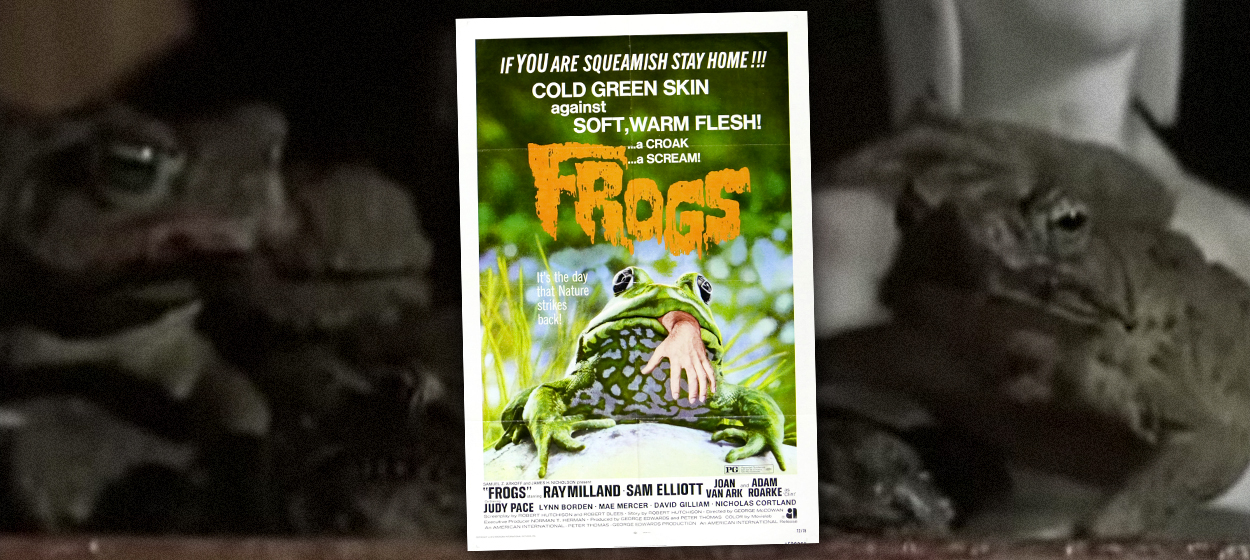

Frogs is the greatest horror movie you've never seen

On the contemporary terrors of watching murderous frogs pursue Sam Elliott 46 years ago

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

You've seen The Birds. You've maybe even seen Godzilla. But one thing is for sure: You have never seen anything like the 1972 eco-horror movie Frogs.

Unless you suffer from ranidaphobia, frogs, as a concept, might not seem terribly frightening. Sure, some are poisonous, and there are entire folklores and religions that revolve around the amphibians being bad omens. But when it comes to movies about animals you don't want to run into, creature features like Alligator, Slugs, and Big Ass Spider seem like more obvious choices.

Frogs, though, is great. Maybe not from an artistic standpoint, or even especially a horror standpoint — the worst scene is probably a man covered in tarantulas, just because imagining how they got those shots makes me squirm. Frogs is horrifying primarily as a relic from a quainter time, when it seemed like nature really could strike back, before organizations like the United Nations were issuing reports saying we've done nearly irreparable damage to the globe.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Let me take you through the plot, which is insane.

The first thing you learn about Frogs is that Sam Elliott is in it. Importantly, it is a rare clean-shaven Sam Elliott, minus his Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid mustache. He plays a dashing canoer with the inconceivable name "Pickett Smith," and you know he is the good guy because he peacefully takes pictures of frogs. A man in a speedboat flips his canoe over, and you know this is the bad guy because he has an extremely villainous name, "Clint Crockett" (Adam Roarke). Clint and his sister, Karen (Joan van Ark), feel bad, sort of, for flipping Sam Elliott's canoe over, so they take him back to their grandfather's private island, which is infested with frogs (you see where this is going).

There Sam Elliott meets Jason Crockett (Ray Milland, coming out of nowhere), who rules his island with an iron fist. Seemingly modeled after the Southern patriarch Big Daddy from Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, Jason is preparing to celebrate his birthday, which also happens to be America's birthday as it's the Fourth of July. And by God, he's not going to let some pesky frogs ruin the occasion. In this scene we also get the perfunctory explanation of why there are so many frogs from Sam Elliott: "Animals overpopulate. They'll die off by next year." Not if you die off first.

I should mention that all of this happens with a low, ominous croaking in the background and some very disapproving reaction shots from frogs.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

"With all our technology and all my money, we still can't get rid of these frogs," Jason complains to Sam Elliott at this point, and you realize he might be onto something. No matter how much pesticide you spray on your private island, nature will always win!

This is a rather dated way of thinking about things, of course, but Frogs is of a simpler era. Released the same year that DDT was finally banned, it was one of several eco-horror films to come out of the 1970s warning of man's destructive tendencies toward nature — Long Weekend, about a camping trip gone awry, was another. You know the Crocketts are going to die because one of them whines, "Daddy, did you know the government is forcing us to put strainers on our paper mill?"

While all this hand-wringing about Uncle Sam is going on, Sam Elliott gets roped into doing chores for Jason and is sent to find a guy named Grover, who was tasked with spraying pesticides to get rid of the frogs. Grover, as you might expect, is dead and covered in snakes.

Cue a triumphant frog reaction:

As many angry viewers have pointed out, the frogs themselves don't actually do a whole lot of murdering in Frogs. Snakes do most of the heavy lifting, and there are also some geographically misplaced lizards and alligators that get in on the action. One person dies by breaking bottles of poison (???) in a greenhouse. Another person is ambiguously killed by a turtle. All the while, a cacophony of croaks rages in the background, like the primal scream of Mother Earth herself.

By the time our heroes realize that nature is taking back the island, it is — spoiler alert — too late. Sam Elliott only manages to escape by taking his shirt off and bashing a water moccasin with an oar. The rest of the Crockett clan is not so lucky — Jason, who stays behind, is haunted by the animal trophies on his walls that reanimate to roar and (in the case of a fish) "chatter" at him. It is only a matter of time before he is overcome by the hoard of frogs that have decided, 90 minutes into the movie, to at last get in on the whole "killing humans" thing.

As absurd as this all is, Frogs is played entirely straight. It is almost painfully earnest. After all, the 1970s were a turning point for environmentalism, both a time for the cheesy warning of Frogs and the eventual victory of the Crocketts of the world. "Something happened [in the 1970s] to allow environmentalism's antagonists to stigmatize its erstwhile stewards as unstable alarmists and bad-faith prophets — and to call their warnings at best hysterical, and at worst crafted lies," explains Frederick Buell in his book From Apocalypse to Way of Life: Environmental Crisis in the American Century. What once was a zeitgeisty musing by Sam Elliott — "what if nature were trying to get back at us?" — is now entirely comedic. Jason Crockett might not have had the technology and money to get rid of frogs, but we do. Already more than 112 species of frog are thought to have gone extinct since 1980 as a result of the human impact on climate change.

Frogs is wild. It's hilarious. It's the horror movie you didn't know you needed. But its horror comes, in part, from how naive we were and how cynical and fatalist we've since become.

When Jason declares "I still believe man is master of the world," we know he is begging for his eventual, slimy demise. Only decades later, though, can we recognize that maybe we also deserve our amphibious retribution.

Jeva Lange was the executive editor at TheWeek.com. She formerly served as The Week's deputy editor and culture critic. She is also a contributor to Screen Slate, and her writing has appeared in The New York Daily News, The Awl, Vice, and Gothamist, among other publications. Jeva lives in New York City. Follow her on Twitter.

-

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’The Week Recommends Mystery-comedy from the creator of Derry Girls should be ‘your new binge-watch’

-

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960s

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960sThe standout shows of this decade take viewers from outer space to the Wild West

-

Microdramas are booming

Microdramas are boomingUnder the radar Scroll to watch a whole movie