Do deficits still matter?

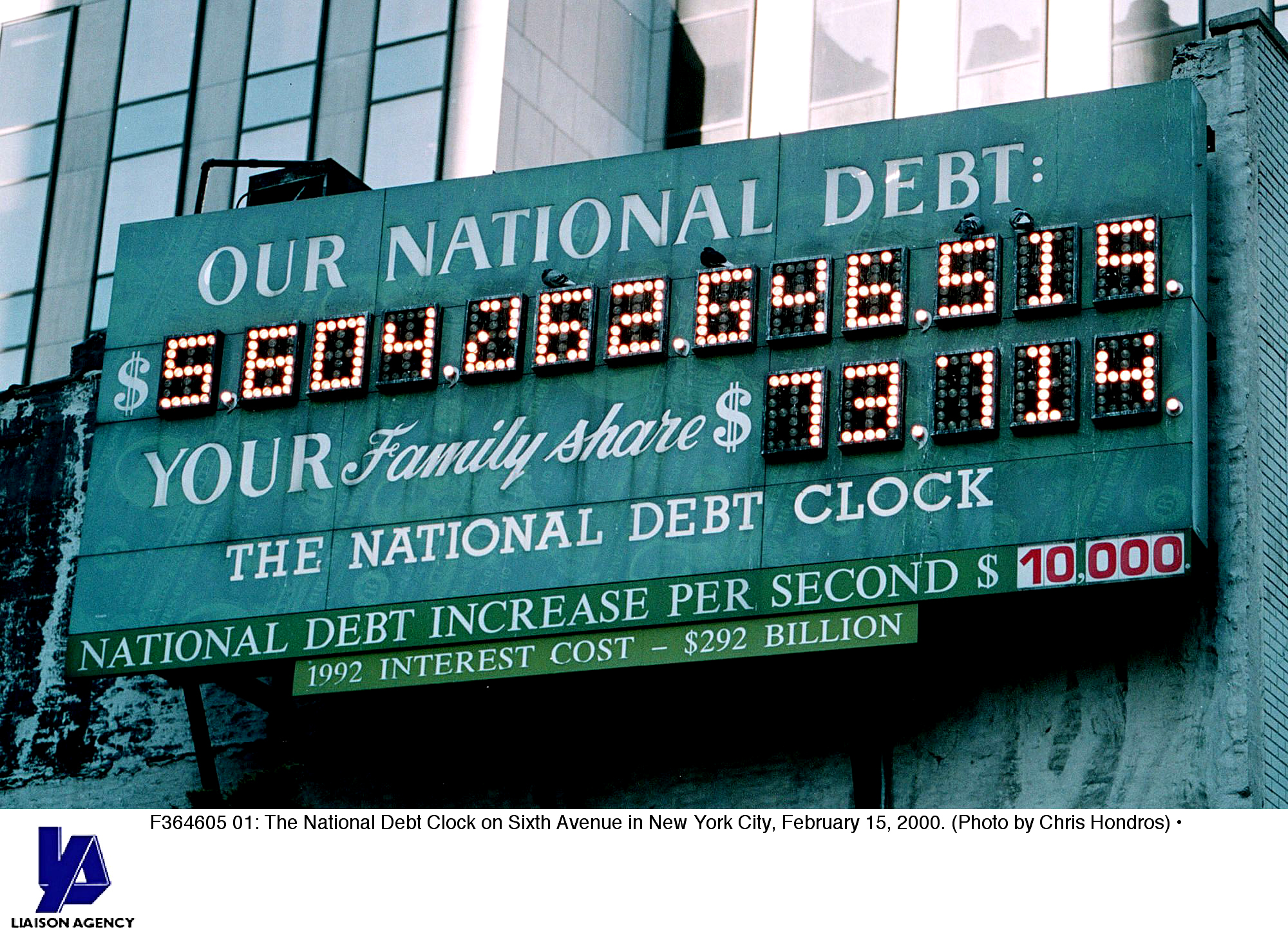

The national debt hit $22 trillion last week. Is that a problem?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The smartest insight and analysis, from all perspectives, rounded up from around the web:

The national debt hit $22 trillion last week, but there's little pressure on the government to rein in spending, said David Harrison and Kate Davidson at The Wall Street Journal. Annual deficits will top $1 trillion starting in 2022, and the Congressional Budget Office projects the U.S. government's debt could reach 93 percent of GDP — the country's total annual economic production — by the end of the next decade. That's a key threshold; one influential study "found that countries with debt loads greater than 90 percent of GDP tended to have slower growth rates." So far, though, the run-up in debt hasn't seemed to hurt the economy. Investors have been happy to "keep lending to the U.S. in good times and bad, regardless of how much it borrows." All the big increases in government spending haven't caused a spike in inflation, either. "Now some prominent economists say U.S. deficits don't matter so much after all."

For years economists scolded countries for borrowing too much, said Noah Smith at Bloomberg. These days, however, many of them think that as long as interest rates are lower than the economy's rate of growth, the government debt burden will effectively "shrink all on its own." If that's true, the U.S. "can afford to add some debt — say, another 60 percent of GDP — to its books with little danger." At some point, "fiscal prudence will have to re-enter the conversation." For now, though, the latest research shows that, in effect, we can keep borrowing at current levels up to the year 2043.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Here's what will happen if we do that, said William Gale at CNN: "The problem will be bigger, the economic consequences will be more severe, and the political challenges of cutting spending and raising taxes will grow." It's fashionable now to say that deficits no longer matter and so we can embark on massive new programs of government spending like the Green New Deal and "Medicare for all." Meanwhile, we're accumulating the worst sort of debts — not ones for investing in infrastructure and education, but the kind that come from "an aging population and large, poorly targeted tax cuts." Eventually, these deficits will choke off investment and savings. The longer we wait to address the record deficits, the more painful the adjustment will be.

If government debt really becomes a problem, we'll know very quickly, said Jason Furman and Lawrence Summers at Foreign Affairs. "The financial markets give immediate feedback about the seriousness of the budget deficit." But we're not there now, and probably not anywhere close. With low interest rates, there's no magic number at which government debt is too big. Japan's national debt has been well over 100 percent of its GDP for almost two decades with no ill effects. The moment investors think it's gotten harder for the U.S. to pay its debts, interest rates will rise, signaling that we need to cut spending or raise taxes. "But no alarm bells ring when the government fails to rebuild decaying infrastructure, properly fund preschools, or provide access to health care."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

The week’s best photos

The week’s best photosIn Pictures An explosive meal, a carnival of joy, and more

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word