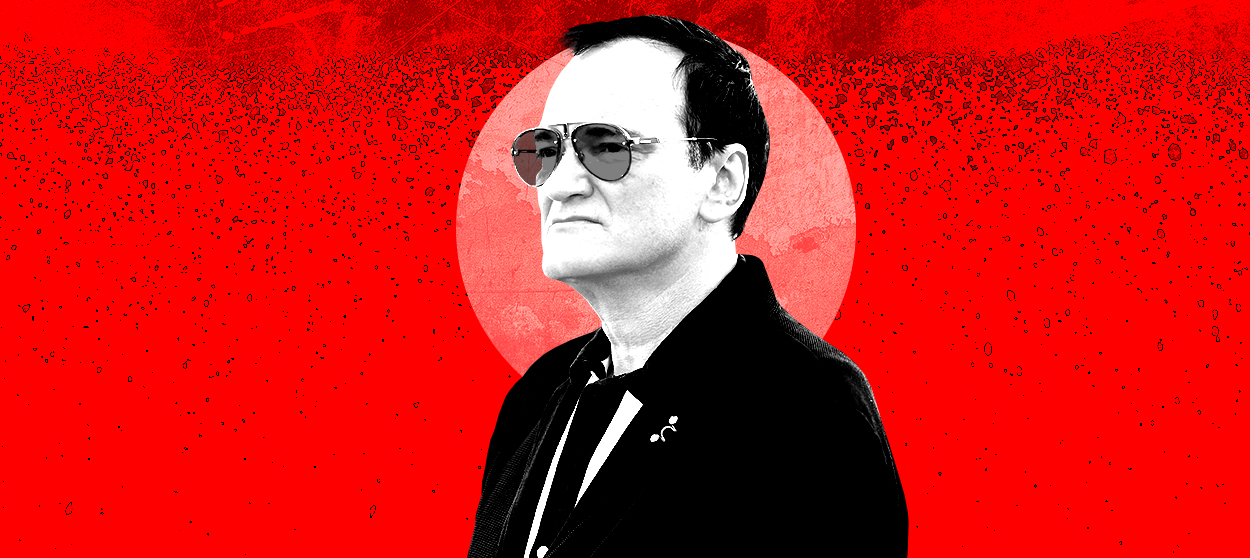

In defense of Quentin Tarantino's over-the-top violence

The director loves to make audiences squirm. His new film is no exception.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It all started with the ear.

In retrospect, there couldn't have been a more fitting note for Quentin Tarantino to begin his career on. Horrified contemporaneous reviews of his 1992 debut Reservoir Dogs queasily attempted to tip-toe around describing the now-famous scene in which Mr. Blonde (Michael Madsen) saws off the ear of a bound and gagged cop. Even though you don't see the actual severance on screen — a pan serves to do the work of covering your eyes for you — critics were stunned. "One of the most aggressively brutal movies since Sam Peckinpah's Straw Dogs," gulped The New York Times. Variety warned that "a needlessly sadistic sequence ... crosses the line of what audiences want to experience."

Twenty-seven years on, Tarantino is still dancing gleefully across that line, poised as he is to upset audiences' stomachs on Friday with his already-controversial Manson murder extravaganza, Once Upon a Time in ... Hollywood. Despite the nearly three decades that have passed since "the ear" hullabaloo, though, Tarantino's excessive use of gore remains the emotional crescendo of his filmmaking — and isolates the unique, affecting abilities that filmmaking has over all other arts.

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Unfortunately, nothing brings out America's moral banshees quite like the endless, ongoing debate about violence in film. By the time Tarantino was working on Kill Bill in the early 2000s, the wailing over his enthusiastic use of gore was already growing stale. "He knows now, from bitter experience, that if he indulges in flamboyant, over-the-top violence, American audiences and critics will talk about that more than about almost anything else: it will be taken seriously, as a ponderous moral issue," The New Yorker wrote in a 2003 profile.

But while Tarantino's critics have long sought to link his on-screen gore to the violence prevalent in everyday life, the two examples could not be further from each other. Gore in Tarantino's films is used as yet another tool to emphasize the artifice — and, contained within that, the possibility — of filmmaking as a medium.

Violence in Tarantino's films is virtually never reflective of what violence looks like in real life: It is unnatural, unrealistically bloody, and heavily stylized. Severed bodies magically contain more than the standard 5.5 liters of blood in order to supply dramatic splatters; limbs regularly go flying; and a buddy being accidentally shot in the face is an inconvenience to the shooter, rather than a horror. Brutally creative ways to die are also explored, ranging from a stunt car sawing off a person's face via the revolution of a back tire to Once Upon a Time in ... Hollywood's novel deployment of a wall telephone. Tarantino has likened his slasher scenes to doing what dance sequences do in musicals: function as choreographed spectacles that are intended to be relished.

Even this ability to "enjoy" (or at least endure) Tarantino's gore is singular to the art of filmmaking. There is a chasmic difference, after all, between watching someone's ear about to get sawed off and reading about it or listening to the victim's disembodied howls in a radio play. Television, while technically sharing the same potential as the movies, rarely has a chance to depict excessive gore due to censors. Only in the movies can over-the-top murder be yet another tool of emotional manipulation. "I will be like, 'Laugh, laugh, now be horrified,'" is how Tarantino put his role as a director to The Telegraph.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Tarantino's interest in the gulf between narrative film and "real life" is one he's been chasing his whole career. It is laid barest, though, in Inglourious Basterds, which takes the possibilities of filmmaking to the extreme by exploring how it is possible even to kill Hitler in the movies. As Germany's Der Spiegel critic Georg Seesslen raved (relayed into English by Agence France-Presse), "pure cinematic fantasy can do a better job of getting to the truth than historical authenticity: fiction trumps reality."

But often when it comes down to it, Tarantino's embrace of blood and guts is a lot simpler than any of that: It's just a heck of a lot of fun. Admitting that nevertheless feels almost perverse. There is a distinctly American paranoia that conflates an audience member's enjoyment of on-screen violence with some sort of real-world emotional sickness. Whenever an especially tragic incident is perpetrated by a young person in America, fingers are immediately pointed toward the influence of television, movies, or video games, and done so at the expense of a discussion about the real issues.

Tarantino is sardonically aware of this: Toward the end of Once Upon a Time in ... Hollywood, one of the members of the Manson family rants about needing to exact revenge on the actors who've helped make murder the bread and butter of the American entertainment industry. Her monologue is followed almost immediately by one of Tarantino's most violent and shocking sequences in his career to date — as if to rub the gore directly in the face of anyone pearl-clutching about some greater implication behind violent movies.

"Violence is just one of many things you can do in movies," Tarantino is on the record as saying. "If you ask me how I feel about violence in real life, well, I have a lot of feelings about it. It's one of the worst aspects of America. In movies, violence is cool. I like it."

But in painting the screen red, Tarantino is doing a whole lot more than just being provocative. He's celebrating what sets filmmaking apart as an art, what makes it special, and why — despite the occasional bouts of nausea it might induce — it keeps us coming back again and again for more.

Jeva Lange was the executive editor at TheWeek.com. She formerly served as The Week's deputy editor and culture critic. She is also a contributor to Screen Slate, and her writing has appeared in The New York Daily News, The Awl, Vice, and Gothamist, among other publications. Jeva lives in New York City. Follow her on Twitter.