Iran can't conquer America. But we can still lose.

How America's impregnability blinds us to the other perils of war

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

When the news broke Thursday night of President Trump's airstrike assassination of Iranian Gen. Qassem Soleimani, I mentioned it in a group chat including a friend who lives in Manhattan. In my professional opinion, she messaged back, did she have time to sing her song at the karaoke happy hour she was attending, or should she head home immediately to call her mom one last time before the bombs obliterated Midtown?

My friend was joking, of course, but it's a joke that becomes disastrous in the mouths of the policymakers who dictate our country's foreign affairs. It's a joke that helps explain why this assassination happened in the first place — why our foreign policy careens from one military intervention to another as if consequences can never catch us.

It's also a joke based on a truth, albeit a truth gravely misinterpreted. The truth is that though Iran is bent on vengeance and has plenty of options for its execution, it realistically cannot pose an existential threat to the United States. There is no scenario in which Iran wins a war with America in a conventional sense, in which Iranian planes bomb New York City and Iranian troops march through Washington, D.C., and suddenly the Constitution is gone and we're all swearing fealty to Ayatollah Khamenei.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

When Americans imagine losing a war, this is our default imagery. Our mental stage is set with props from World War II — where the Axis powers potentially could have conquered the United States had things gone very differently — and the Cold War — which, had it turned hot, could have seen Soviet nukes decimating major American cities (and vice versa). Pondering defeat takes us to The Man in the High Castle, a compelling alternate history precisely because its fanciful premise is still plausible, just as the idea of Iran accomplishing a comparable conquest is utterly implausible. (Iran's entire GDP, $440 billion as of 2017, is less than the Pentagon's annual budget; and even though it began breaching terms of the nuclear deal following Trump's withdrawal from the agreement, Iran does not have nuclear weapons. The power disparity between Tehran and Washington is immense.)

The trouble is conquest is not the only negative outcome of war. And I suspect failure to add that realization to recognition of America's near-total imperviousness to traditional conquest accounts for much of the stupidity in our foreign policy. Because we know one bad consequence isn't possible, we invade, airstrike, assassinate, and sanction at will as if no bad consequences are possible.

This habit is not original to the Trump administration, but it is exacerbated by the president's ignorance, petty pride, changeability, and impulsivity. He seems unable to think with clarity about any moment but the present, and that makes him extra susceptible to reckless advice and shortsighted choices. The Soleimani strike may prove the most destructive of his choices yet.

A rudimentarily prudent foreign policy would always consider at least two sets of consequences before any military action. First, what will be the human cost?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Civilian deaths in the war in Afghanistan are estimated in the tens of thousands and in Iraq in the hundreds of thousands. U.S. intervention in Yemen has helped produce the world's most acute humanitarian crisis — an estimated 85,000 Yemeni children younger than 5 starved to death between 2015 and 2018. American civilians are comparatively safe from the violence of war and terror, but we are not invulnerable, nor are military casualties to be dismissed from our accounting. War with Iran would have enormous human costs, and killing Soleimani is a major step in that direction (if not a functional declaration of war itself).

The second consideration is the path to conclusion. Here is a lesson Washington ought to have learned once and for all in Vietnam but which has been demonstrated anew by our misadventures of the last two decades: It is much easier to begin a war than to end one.

We are not at risk of foreign subjugation, but that does not mean we are not at risk of losing. What are the United States' perpetual wars if not losses? Is there any way to describe what we're doing in Afghanistan as victory? Is participating in the starvation of Yemen a triumph?

For a superpower, defeat doesn't look like conquest. It looks like fighting forever, killing and being killed for nothing, funding corruption and calling it "building democracy," wasting trillions and calling it strength, creating terrorists and calling it counter-terrorism, assassinating national heroes and insisting the act will be met with mass gratitude.

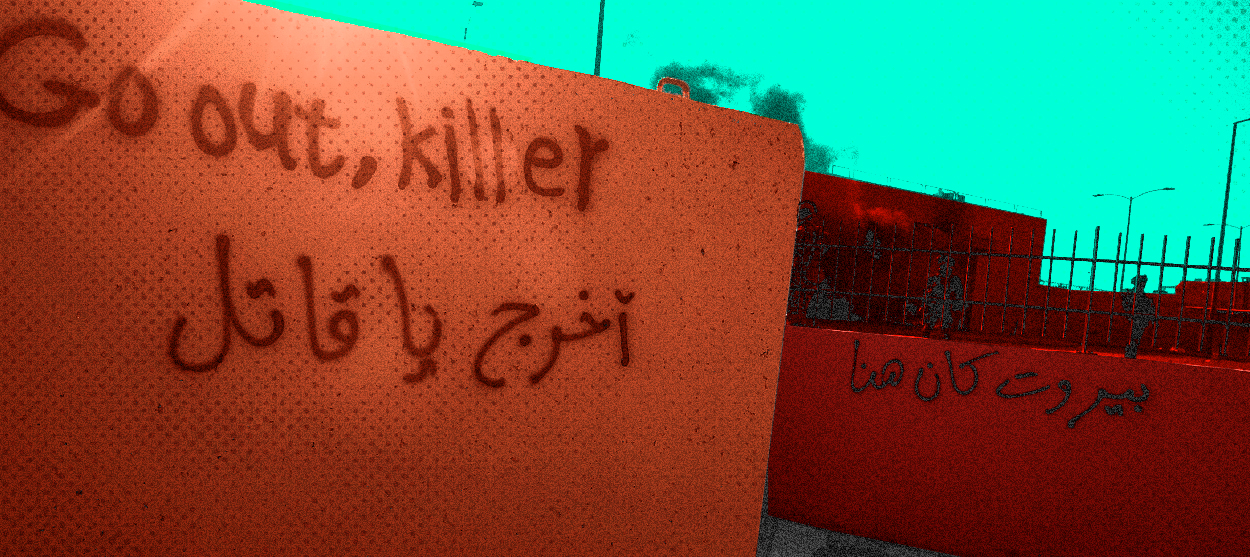

Defeat looks like death, dissipation, and self-delusion. It's time we cleared out our World War II scenery and made way for this modern set. It's time to recognize that if we go to war with Iran, this type of defeat is all but a foregone conclusion.

Bonnie Kristian was a deputy editor and acting editor-in-chief of TheWeek.com. She is a columnist at Christianity Today and author of Untrustworthy: The Knowledge Crisis Breaking Our Brains, Polluting Our Politics, and Corrupting Christian Community (forthcoming 2022) and A Flexible Faith: Rethinking What It Means to Follow Jesus Today (2018). Her writing has also appeared at Time Magazine, CNN, USA Today, Newsweek, the Los Angeles Times, and The American Conservative, among other outlets.