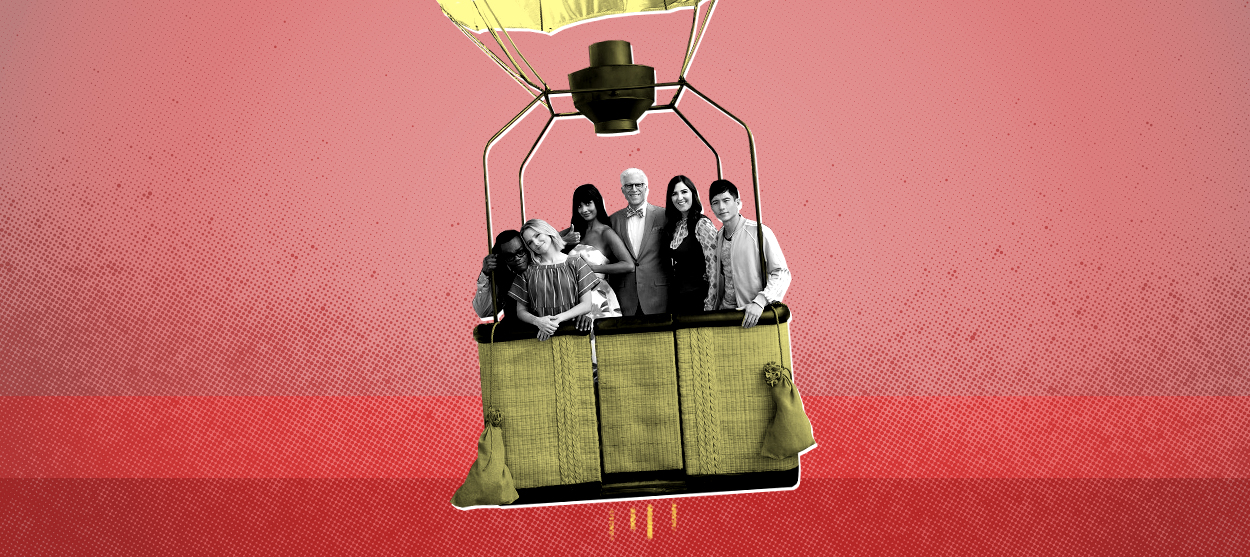

All good things must end, even The Good Place

The show is stepping beyond the big green door to its final rest

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

After four seasons and four years on air, it's fitting that Michael Schur's The Good Place should conclude with a disquisition on the merits of eternity. Is paradise unending really all that it's cracked up to be? If bliss is granted with the snap of our fingers, if our hearts' desires are so easily achieved, and if we have all the time in the afterlife to indulge them without worrying about dying before we get around to each and every one of them, then maybe Heaven is actually Hell. At the very least, it's kind of a bummer. When everything is possible, nothing matters, and when nothing matters, minds go to seed. Even Hypatia of Alexandria can't endure such conditions without turning into a total "smooth brain."

The Good Place's Eleanor (Kristen Bell), Chidi (William Jackson Harper), Tahani (Jameela Jamil), and Jason (Manny Jacinto) have an elegant solution: An after-afterlife, kept behind a green door. Step right through, and be at peace forever. Heaven's great, but good times have to end eventually.

I suppose the same is true of television. We're past the point where "golden age" is an adequate descriptor for the days of peak TV. Frankly, even "peak TV" has outlived its usefulness for characterizing the 2010s, and now the 2020s, where there's just too damn much TV to watch and series tend to go on, and on, and on, whether they deserve to or not.

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Consider that there's still a camera crew documenting the lives of the extended Dunphy family, that new crises unfold and steamy romances still heat up in the halls of Grey Sloan Memorial Hospital, and that Bart, Lisa, and Maggie haven't aged a day since 1989; think about the stranglehold that Game of Thrones has maintained over pop culture for the last decade, and that with a successor series on the way for 2022, its grips will slacken only briefly before choking out entertainment sites afresh.

Too much of a good thing is a problem. Mercifully, and not a little ironically, The Good Place understands that problem despite being set in the sweet hereafter — and the sour hereafter, and the second-rate hereafter. There isn't a corner of the great beyond Schur, his writers, and the series' cast haven't explored over the course of its lifespan: the Good Place, which is actually the Bad Place, plus the Medium place, plus the real Good Place, including its filing offices, where good souls are sifted from bad souls, which means that, in accordance with the Good Place's absurd requirements for entry, nobody ends up in the Good Place at all and gets tortured by chainsaw bears forever instead.

Bless The Good Place for ending. As fun as it is watching the gang puzzle over new existential predicaments every week, drawing out their path toward enlightenment after shuffling off their mortal coils defeats the purpose of the show as the contemporary roadmap for goodness we all need, whether we realize it or not, at a moment where goodness is in short supply and badness trickles down from the very top of American society. We are in an era of casual cruelty: Anyone, at any given moment, has the power to taunt, bully, and abuse strangers from hundreds of miles away for such sins as liking The Last Jedi. We're talking about badness in its pettiest form (though even petty badnesses can have meaningful consequences in the real world); it's workaday badness, the kind of badness otherwise good people are guilty of and would end up in the Bad Place for. (Badness in its worst forms, a'la hate crimes and high crimes, comprise a separate category. Most of us won't punch our tickets to the Inferno by shooting up Synagogues or extorting a foreign country.)

Being good takes a lot of work. In The Good Place, as in life, goodness comes naturally to nobody: Not Eleanor, selfish and caustic, not Jason, impulsive and dim, not Tahani, haughty and proud, not Chidi, indecisive and trying. Goodness is relative, too. Tahani's philanthropic endeavors afford her the veneer of goodness, but beneath the veneer lies arrogance and jealousy. Chidi's brilliance, meanwhile, makes him a thorn in the side of his friends and family. He's a man incapable of taking action, whether trivial or urgent, to the detriment of every sucker caught in his orbit.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Television is rarely revolutionary, but Schur's big idea for The Good Place — to massage the contradictions of goodness into a sitcom mold — qualifies. Being good is overrated. The architects of the Good Place, simpering goodie goodies dressed like L.L. Bean rejects, hoodwink Michael (Ted Danson), erstwhile Bad Place architect and reformed career demon, into assuming ownership of the Good Place after rebuilding it; it's a slightly better Good Place, except that perpetual joy and happiness turn inhabitants into mindless zombies. They don't know how to fix the problem, so they dump it on Michael, and, reformed or no, leaving Heaven in the hands of a demon is decidedly not good. If the Good Place architects are paragons of what it is to be good, there would appear to be little hope left for the rest of us — except, of course, for Eleanor, Chidi, Tahani, and Jason, and even Michael and Janet (D'Arcy Carden).

Goodness ultimately isn't about how good you are, but how good you strive to be. That's the legacy of The Good Place, where angels are squirrelly traitors and demons believe in rehabilitation. The show is a testament to goodness as an ongoing spiritual enterprise, the work that people do to be better today than they were yesterday. Anybody can be good if they are willing to put in the effort. The Good Place demonstrates what "effort" looks like, and what goodness takes: Learning, vulnerability, struggle, failure, and most of all, perhaps, the help of a few good friends. Goodness is a journey. Having educated its audience on goodness' labors from 2016 to now, The Good Place has gently arrived at the end of its own, stepping beyond the big green door to its final rest.

Want more essential commentary and analysis like this delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for The Week's "Today's best articles" newsletter here.

Bostonian culture journalist Andy Crump covers the movies, beer, music, and being a dad for way too many outlets, perhaps even yours: Paste Magazine, The Playlist, Mic, The Week, Hop Culture, and Inverse, plus others. You can follow him on Twitter and find his collected writing at his personal blog. He is composed of roughly 65 percent craft beer.