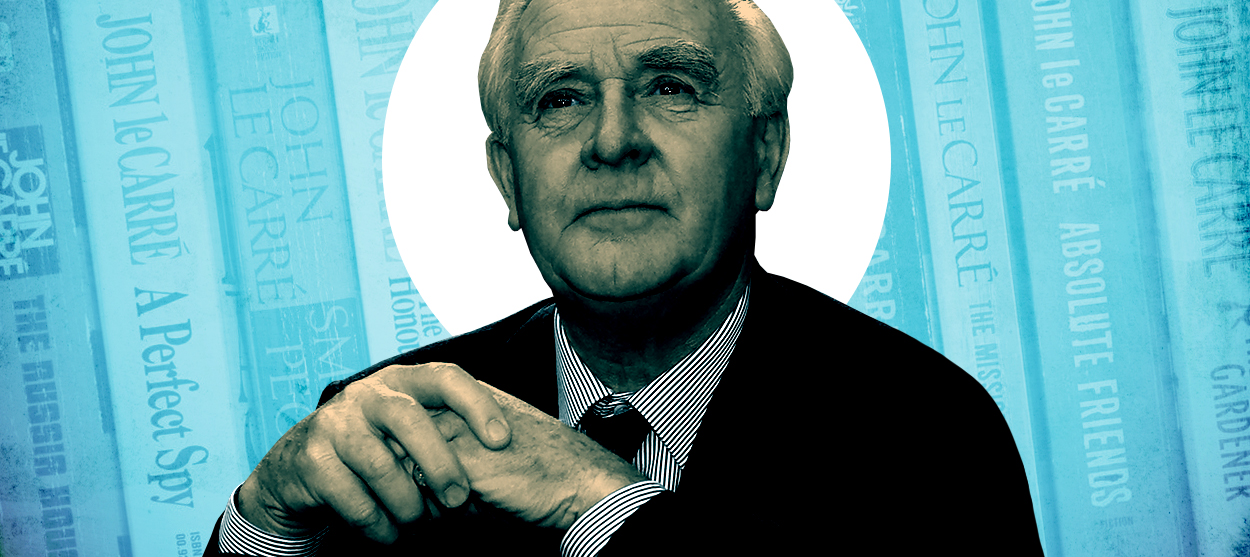

The unrivaled John le Carré

How the spy novelist changed English literature

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

With the death of John le Carré on Sunday at the age of 89, the English-speaking world lost its most considerable living novelist, a seemingly tireless craftsman who wrote bestsellers in six successive decades beginning in the 1960s, a feat rivaled only by Agatha Christie and P.G. Wodehouse.

This was not the only sense in which le Carré resembled the inventor of the Drones Club and Blandings Castle. It is absurdly fitting that, like Bertie Wooster and Sherlock Holmes before him, George Smiley did not age. Recruited into the Circus, as he fittingly referred to MI6, in the years following the First World War, le Carré's most famous creation lived long enough to deplore the Brexit cause. Smiley belongs, like a reverse Pooh Bear, to a land of eternal old age, of dingy flats, warm vodka, and cigarette smoke. He is at heart a nostalgist, though his Never-Never Land is the Germany of Schiller and Goethe rather than the supposed glories of the British Empire. I could not understand the outrage that greeted the publication of A Legacy of Spies, in which our hero, making what I now sadly realize will be his final appearance in print, declares that everything he did was directed against the evil of communism in the hope of bringing Europe "out of her darkness" to a new era of romanticism.

Le Carré wrote with an unrivaled technical facility. It is not an exaggeration to say that in The Spy Who Came in From the Cold, the reader is captivated until the very last sentence, one of the cruelest in English fiction. But it was descriptive writing, his evocation of places, especially those now long vanished, and of characters that raised him above the Flemings and Ludlums. A map of pre-1997 Hong Kong could be redrawn from the pages of The Honourable Schoolboy. Despite, or perhaps because of, his bizarre equivocal relationship with his own father, he wrote with especial tenderness about parents and children. Here he is describing a school holiday taken by Magnus Pym, his most autobiographical hero, and his itinerant father, the itinerant con man Rick:

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

They rode their bicycles on the sand and skimmed pebbles on the waves. They lay in the dunes munching foie gras and Ryvita. They wandered through the little town and wondered whether Rick should buy it. They stared at the church and promised never to forget their prayers. They made a goal out of a broken gateway and kicked the football at each other all the way across the world. They kissed and wept and bear-hugged and swore to be pals all their lives and go bicycling every Sunday even when Pym was Lord Chief Justice and married with grandchildren. [A Perfect Spy]

A friend of mine told me recently that he cannot read this passage without hot tears welling up above his cheeks.

As the Cold War drew to its conclusion and finally ended, many argued that le Carré had lost his way. Nearly every major critic echoed this verdict, though few could agree about which books were the bad ones. The Little Drummer Girl, his foray into the world of Israeli politics, was panned by David Pryce-Jones in the pages of The Spectator but praised by William F. Buckley of all people in The New York Times. For my part I think the best of the non-Cold War books is A Most Wanted Man, which became an excellent film starring Philip Seymour Hoffman.

I look forward to reading the revised version of Adam Sisman's biography of the man who was born David Cornwell in 1931, one of the strangest and most enjoyable books of its kind published in many years. So many aspects of his life remain mysterious, not least of all the origins of his pen name (French for "the square"). It is probably unlikely that we will ever know the truth about his childhood, about which he himself seems to have either lied or, perhaps more reasonably, guessed in interviews and his odd but absorbing memoir. Yet some things do seem clear, among them the fact that his career in the intelligence services was mostly uneventful, and that his greatest service to Her Majesty was inventing jargon for his characters — "mole," for example — that would go on to be used by actual spies.

Le Carré's death will bring me and, one imagines, millions of others racing back to the novels, above all to A Perfect Spy and the Smiley books. And it will be not as mere "genre" fiction but as English literature that we read them.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Matthew Walther is a national correspondent at The Week. His work has also appeared in First Things, The Spectator of London, The Catholic Herald, National Review, and other publications. He is currently writing a biography of the Rev. Montague Summers. He is also a Robert Novak Journalism Fellow.