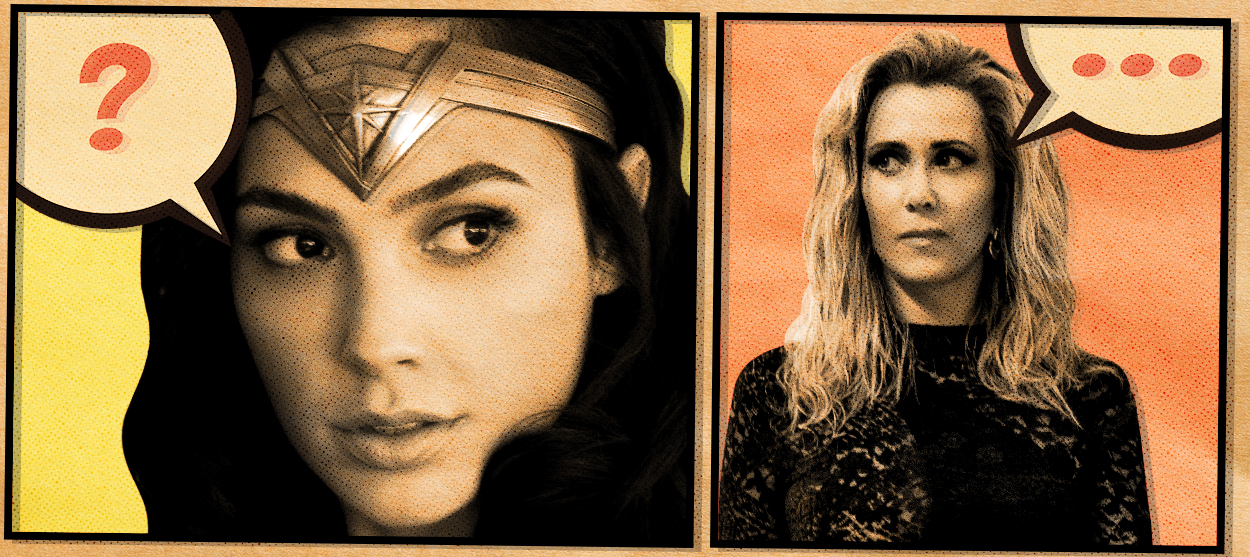

Wonder Woman 1984 is shockingly regressive

How the sequel ultimately undercuts its own goals as a feminist superhero film

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Let's talk about shoes.

More specifically, let's talk about Wonder Woman's wedge heels. Almost exactly one year ago, fans got their first look at Wonder Woman 1984, the sequel to the 2017 smash hit Wonder Woman, with the trailer confirming that Gal Gadot's character still preferred donning impractical footwear when saving the world. The whole thing rekindled a minor controversy over her costume: Yes, Diana Prince is a made-up character — a literal Amazon who doesn't have to worry about twisted ankles like the rest of us mere mortals — but wouldn't she still prioritize comfort and function over wanting to look good?

Diana's blister potential, it turns out, is the least of Wonder Woman 1984's issues (the film is out on Friday on HBO Max). Beyond the movie's intensely cringey script, its incomprehensible geopolitical backdrop, and the upsetting use of digital fur technology, Wonder Woman 1984 ultimately undercuts its own goals as a feminist superhero film by falling back onto regressive tropes about women.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The intense scrutiny on the costumes in the trailer is in some way a testament to the success of the franchise: Fans look to Wonder Woman to uphold a higher standard. The series is intended as an antidote to an industry of otherwise testosterone-fueled comic book movies, ones in which the gendered phrase "superhero" inherently implies the exclusion of superheroines. When the first film came out back in 2017, critics described actually weeping through the film's then-revolutionary fight scenes: "This was the movie — female warriors kicking ass," reflected one. And despite the distinctly third-wave whiff of it all (beauty and power? In this economy?), the result was fun, even if it was "manically straightforward."

Wonder Woman 1984 is set almost 70 years later. Diana, being an Amazon and daughter of Zeus, hasn't visibly aged since World War I, and has moved to Washington, D.C., where she works at the Natural History Museum, using her weekends to save kids at the mall and rescue brides who've fallen over banisters (?). All the while, she continues to mourn her partner Steve (Chris Pine), who had sacrificed himself to save the world during the war. Diana is soon joined at the museum by Barbara Ann Minerva (Kristen Wiig), an awkward, frumpy, and lonely gemologist who finds herself unknowingly in possession of a magical wish-granting crystal. Diana comes in contact with the stone, and inadvertently wishes Chris Pine back into the movie; Barbara's greatest wish, meanwhile, is to be "sexy" and powerful, like her new friend Diana.

Prior to her wish being granted, Barbara is coded as homely via the typical, sexist Hollywood clichés: She doesn't get hit on at work, she wears baggy clothes, and she needs wire-rimmed glasses to see. When the crystal grants her wish, though, she gets her glow-up: She starts wearing tight-fitting clothes, she can magically walk in heels, and — most tellingly — she ditches her glasses. The makeover feels uncomfortably regressive: Don't we know better, at this point, than the trope of the "ugly girl with glasses" who removes them and is suddenly desirable? It feels even more out-of-place in Wonder Woman 1984, which has made such an example out of Diana wearing what she wants, only for Barbara's makeover to follow the most conventional concept of beauty.

Then there's Barbara's wish, which stands in contrast to the movie's other supervillain, Maxwell Lord (Pedro Pascal, who refreshingly shows his face for this role). While Lord wishes essentially for power, Barbara has a more jealousy-motivated wish of looks and popularity and being "special." It's sloppy that the writers (director Patty Jenkins was one-third of the otherwise male team) opted for such stereotypically gendered motivations for their villains. Even Barbara's initial desire to be like Diana plays into cultural pressures that pit women against other women. In better hands, there might have been an opportunity to comment on the way such competition between women complicates feminist solidarity and how Barbara is a victim of a system that upholds the patriarchy, but the script is either disinterested in such an investigation, or missed it entirely. Either way, the ensuing battle between Barbara-turned-Cheetah and Wonder Woman devolves to being exactly that: a catfight.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Even Barbara's eventual transformation into a feline monster has its roots in sexualized portrayals of women. Why does she become a cheetah, after all — a cat whose print is associated with "trashiness" (translated by the website Racked as the mark of a "sexually available lower-class woman")? Is it because she wishes to be an "apex predator?" She very well might have turned into an alligator or a shark or a bear instead, then — only those animals aren't as "sexy." Though full credit where it's due: Jenkins and her team wisely chose against the busty version of Cheetah in the original comics, opting to make Barbara more corrupted, beastly, and frightening.

But even Wonder Woman herself feels regressive in this sequel. Though the character is canonically bisexual, and the first film included queer-baiting lines about how the Amazons don't require men for pleasure, Diana remains disappointingly … well, straight. Sixty-six years after her (brief!) romance with Steve, she is still single, with no suggestion that she's been romantically involved with anyone else. "This storyline was so clearly about Steve coming back, the whole story was about Steve," Jenkins has justified, as reported by Digital Spy. "It's all a love story with Steve." But why does it need to be about Steve? The movie is literally called Wonder Woman! Diana's fidelity to her long, long, long dead boyfriend feels oddly conservative and out-of-character, rather than romantic. (Jenkins likewise wrote off the sexual tension that exists between Wonder Woman and Cheetah in the comics, suggesting any relationship they might have had belongs to a "different storyline").

It's a shame, because the cumulative result is that Wonder Woman 1984 feels like two steps back from the forward stride of Wonder Woman. Though the hero is still a powerful woman, the vocabulary of the film remains rooted in a male-dominated industry, from its use of tropes that historically demean women to baffling missed opportunities to subvert such portrayals.

It is not enough, at the end of 2020, for a female hero to suit up and simply "fight a giant CGI shape just like every other male hero who came before her," to quote Thrillist's Emma Stefansky in summary of the 2017 film. And while I might have accepted Diana's preferred butt-kicking shoes as simple wish fulfillment before, I start to wonder if the lack of progress all around isn't a collection of exceptions, but a rule.

Wonder Woman 1984 doesn't pander or condescend to its female audience members, and for that I applaud it. But it does something that, upon reflection, is perhaps even more unforgivable: it shows little interest in them at all.

Jeva Lange was the executive editor at TheWeek.com. She formerly served as The Week's deputy editor and culture critic. She is also a contributor to Screen Slate, and her writing has appeared in The New York Daily News, The Awl, Vice, and Gothamist, among other publications. Jeva lives in New York City. Follow her on Twitter.

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict