Inside the world of Shirley Hughes

Children’s author and illustrator dies at age of 94

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Shirley Hughes has died “peacefully at home” at the age of 94 after a lifetime of writing and illustrating books treasured by children worldwide, her family have announced.

The best-selling author wrote more than 50 books and illustrated around 200 more, including the Alfie series and Dogger, an award-winning story about a boy who loses his toy dog.

“There’s a strong argument to be made that, if you’ve read Dogger, you can probably relax about other literature,” said author Katherine Rundell in The Telegraph. “Get to Dostoevsky when you can, but you’ve got the basics covered.”

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Hughes made “the world of her books shine with sheer reality”, taking “absolutely seriously the perils and triumphs of young childhood”, Rundell added.

For novelist and screenwriter Frank Cottrell-Boyce, precision is what sets apart works by Hughes, who died at her west London home on Friday following a short illness. “No one since Rembrandt has so perfectly captured the precarious half-balance of the toddler’s toddle,” he wrote in The New Statesman.

Nor has anyone else “depicted ordinary domestic mess so honestly”, he said. The “often slightly tatty and just a bit weary” parents depicted in her books made her world welcoming – “as though she was looking you up and down and saying, ‘Don’t worry, you’ll do.’”

These “engaging characters” and their “immediacy and vigour” came from her “skilful and distinctive illustrations, using pen and ink, watercolour and gouache”, said Julia Eccleshare in The Guardian.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

And in real life, Hughes was “just the person” her fans might have expected her to be, continued Eccleshare. “Usually in a hat, she was effortlessly elegant and graceful, and wonderful company: funny, insightful and kind with a laugh that was both loud and heartfelt.”

No regrets

Hughes was born in 1927 in West Kirby, Wirral, and was the daughter of T.J. Hughes, the owner of a Liverpool department store of the same name. He died by suspected suicide when she was five, leaving his widow, Kathleen, to bring up their three daughters.

In a childhood “with a lot of leisure time”, the future author “spent hours sketching, drawing and writing stories and plays with her two sisters”, said Eccleshare.

These family theatrical productions continued through “years of rationing, blackouts, bombings and crushing tedium” of the Second World War, said Jan Benzel in The New York Times. Hughes went on to study costume design at Liverpool Art School. and then drawing at the Ruskin School of Art at Oxford.

Her books later made her “a beloved figure in England, honoured by Queen Elizabeth II and showered with awards”, Benzel continued.

Hughes he spent “hours at neighbourhood playgrounds, watching the way children moved, stood, ran and played” before returning to her drawing board. She was “fascinated by how children’s physicality conveyed emotion – triumph and shyness, fear and sadness, determination and jubilation, intentionally or not”.

In an interview with The Independent in 2013, she described her life as “unfailingly interesting, inspired by family life”. Her marriage, to architect John Vulliamy, spanned from 1952 until his death in 2007, and she had three children and grandchildren, whom she said really made her laugh.

Greatest regret? asked the newspaper. “I don't go in for them,” Hughes replied.

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warming

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warmingThe explainer It may become impossible to fix

-

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies end

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies endFeature 1.4 million people have dropped coverage

-

All in the family: honoring Norman Lear, the godfather of the American sitcom

All in the family: honoring Norman Lear, the godfather of the American sitcomthe explainer Lear revolutionized television and brought us memorable characters like Archie Bunker and George Jefferson

-

Róisín Murphy: Irish singer in puberty blockers row

Róisín Murphy: Irish singer in puberty blockers rowMoloko star voiced concern over the use of medication by transgender children

-

Timothée Chalamet: the making of a global superstar

Timothée Chalamet: the making of a global superstarIn the Spotlight The American-French actor has transformed from art-house actor to blockbuster star and fashion icon

-

Mick Jagger: five things you might not know about the octogenarian rockstar

Mick Jagger: five things you might not know about the octogenarian rockstarIn the Spotlight The rock legend will celebrate his 80th birthday at a lavish party in London

-

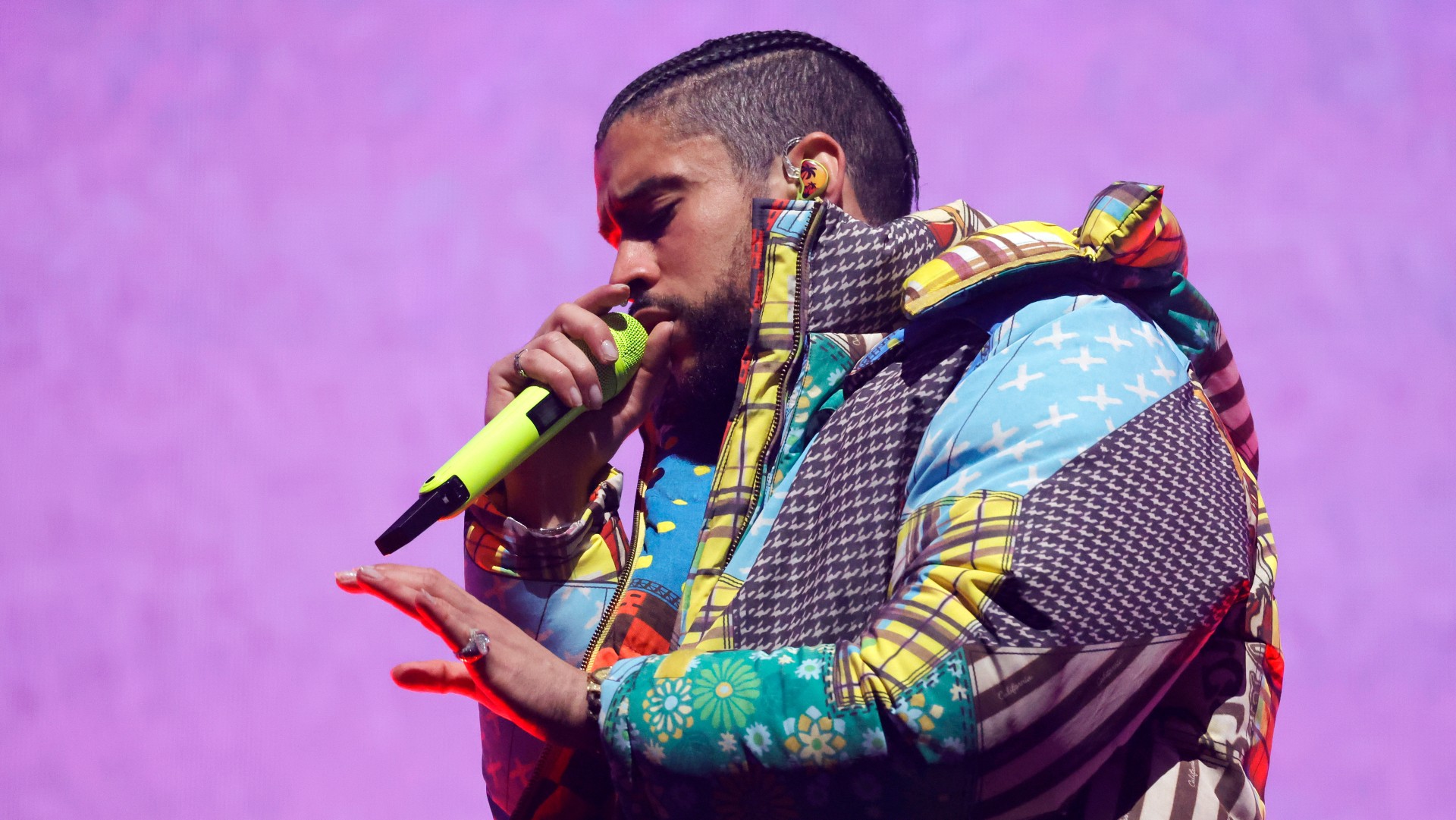

Bad Bunny: world’s most-streamed musician giving a voice to Puerto Rico

Bad Bunny: world’s most-streamed musician giving a voice to Puerto RicoIn the Spotlight Global superstar champions Latino culture, speaks out against corruption and challenges gender norms

-

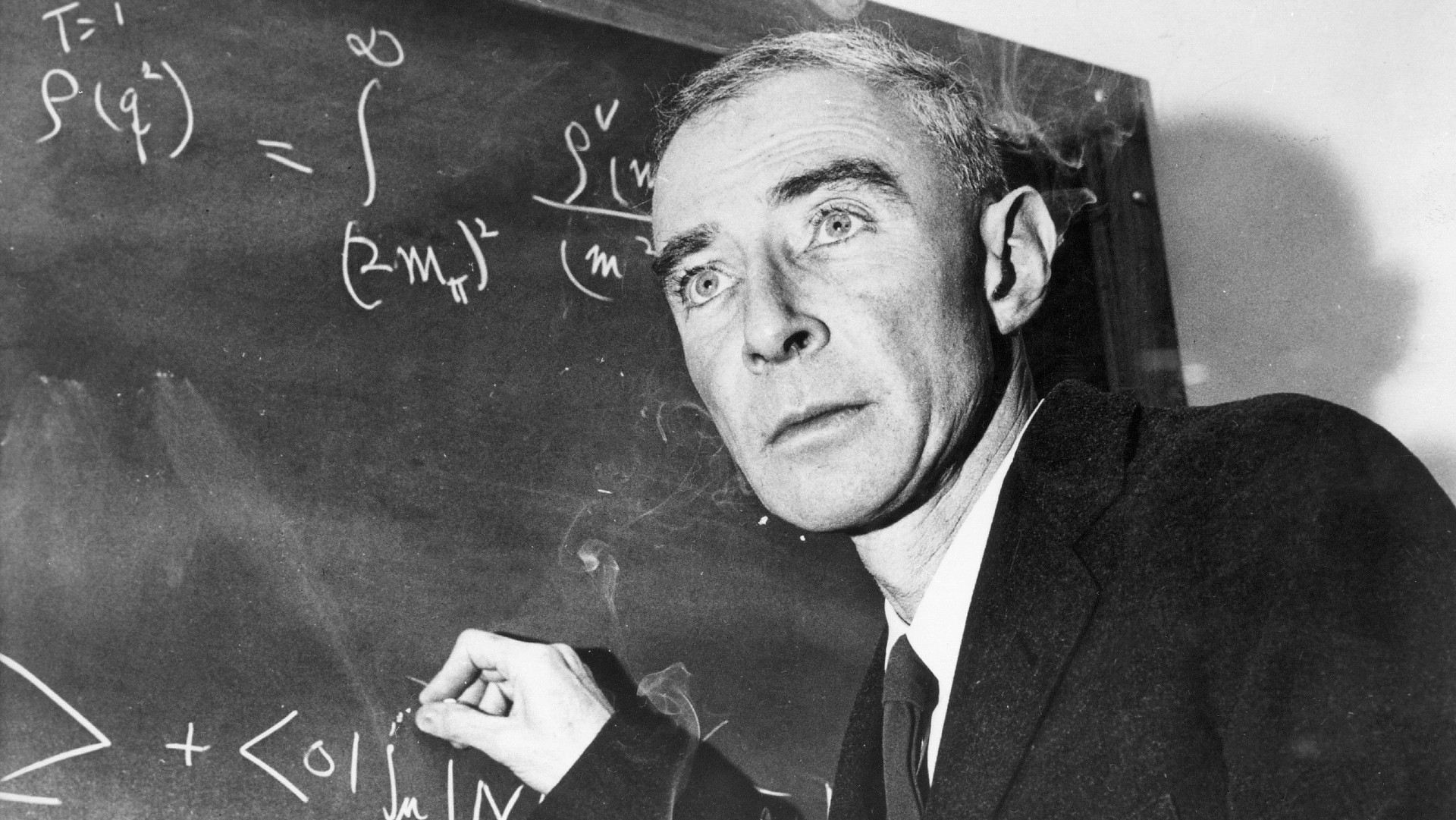

J. Robert Oppenheimer: the real ‘father of the atomic bomb’ at centre of new blockbuster

J. Robert Oppenheimer: the real ‘father of the atomic bomb’ at centre of new blockbusterIn the Spotlight The physicist who led the Manhattan Project has become a martyr for some but his legacy is more complicated

-

Robert F. Kennedy Jr: conspiracy theorist and Democrat challenger

Robert F. Kennedy Jr: conspiracy theorist and Democrat challengerIn the Spotlight The political scion and vaccine sceptic is taking on Joe Biden in battle to be the party’s 2024 nominee for president

-

Jodie Comer: from Holby City to Hollywood

Jodie Comer: from Holby City to HollywoodIn the Spotlight Actor has had a meteoric rise courtesy of award-winning performances in Killing Eve and now Prima Facie