Shakespeare's First Folio: 400 years in print

First published in 1623, seven years after his death, the weighty tome includes Macbeth, Antony and Cleopatra, Julius Caesar

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Shakespeare seems to have been more interested in success on the stage than in seeing his words in print.

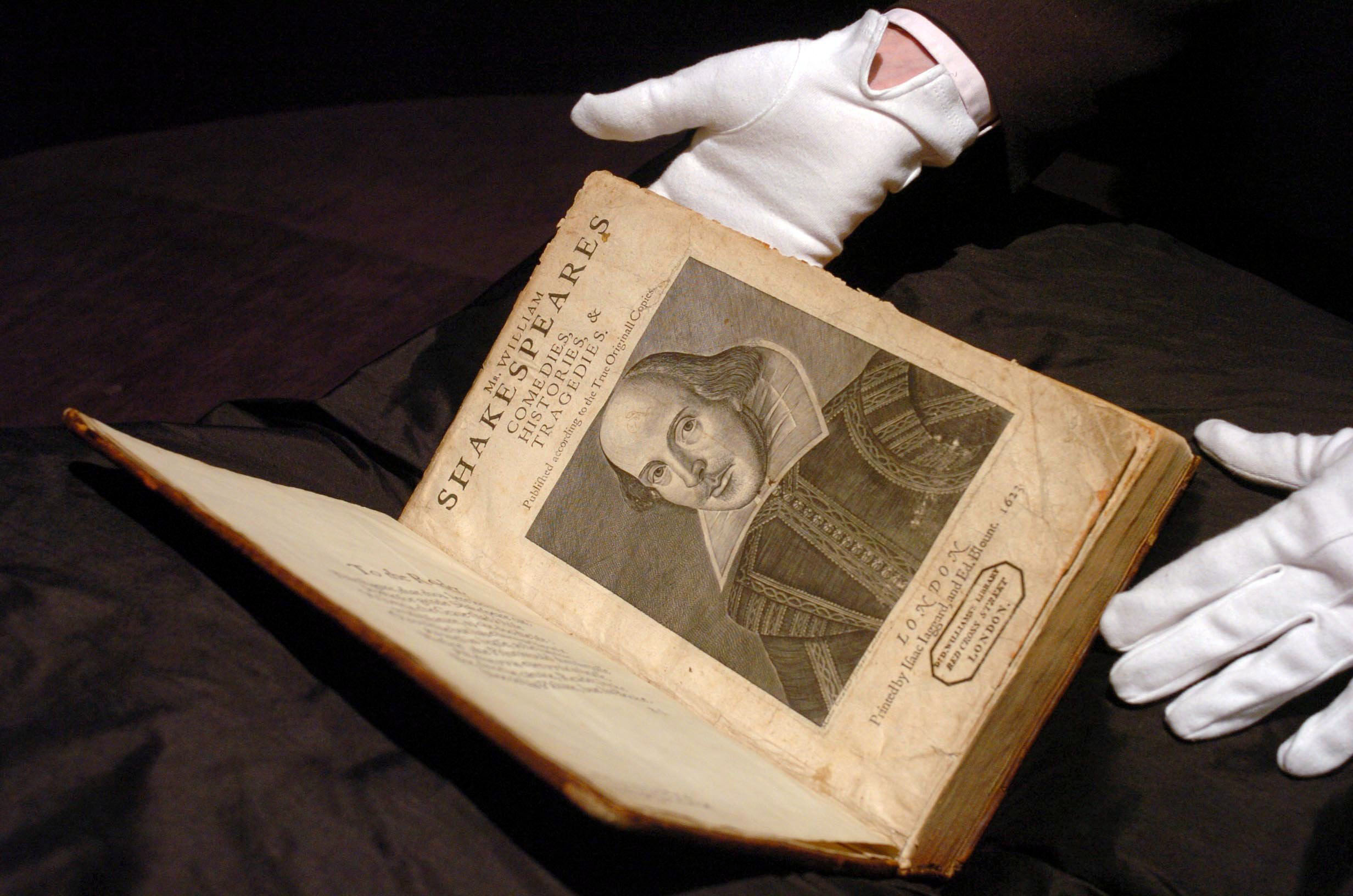

In his lifetime, he published three books of non-dramatic poetry, but only about half of his plays could be bought, in cheap volumes called quartos, sometimes pirated – "diverse stolen and surreptitious copies" – roughly the size of a modern paperback. Mr William Shakespeare's Comedies, Histories and Tragedies, now known as the First Folio, was published in 1623, seven years after his death.

Its more expensive 900-page format implied that these play scripts were serious literature, as not everyone would have thought then. More importantly, without it, we wouldn't have 18 plays, including Macbeth, Antony and Cleopatra, Julius Caesar, As You Like It, Twelfth Night, Measure for Measure, or The Tempest – about half of Shakespeare's plays in total – and many of the others would look quite different.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Who put the book together?

The main movers were John Heminges and Henry Condell, who, like Shakespeare, were actors and part-owners of the King's Men, a successful theatre company. The co-publisher was Edward Blount, a star of the Jacobean book trade. Various smaller booksellers, who owned rights in some of the plays, were also brought on board. The printing was handled by William and Isaac Jaggard, a father-son team based near the Barbican; scholars have shown that at least five of their employees worked on the pages (see box). Shakespeare's friend and rival Ben Jonson wrote a prefatory poem and a eulogy calling him the "soul of the age". The Folio also features a frontispiece by the engraver Martin Droeshout, one of only two images that definitively depict Shakespeare.

Were the printers working from Shakespeare's scripts?

The First Folio says it contains Shakespeare's works "as he conceived them", unlike the "maimed and deformed" versions put out by earlier publishers. In reality, Heminges and Condell seem to have worked from a range of sources, and they had trouble tracking down a few of the texts. Troilus and Cressida arrived too late to be listed on the contents page, and three other plays didn't turn up at all. Some of them probably were in manuscript form, written in Shakespeare's hand, and some of these were sufficiently hard to read that a professional scribe, Ralph Crane, was hired to make clearer copies. Others were taken from earlier printed versions and "promptbooks", probably with scribbled revisions and annotations, which would have given the Jaggards' men further headaches.

How reliable were the results?

As far as we can tell, the Folio caught a pretty good snapshot of scripts used by the King's Men. It's probably a mistake to imagine Shakespeare writing a play once and for all: scripts were adapted and updated, by him or by others. In 1606, for example, Parliament started fining actors for taking the Lord's name in vain. Someone at the King's Men then removed the religious swear words from Hamlet, Henry IV, Part 1 and Othello, and the censored versions are preserved in the Folio: Hamlet says "O, heaven!" instead of "O God!" The Macbeth we've got seems to have been adapted for indoor performance, and quite what's going on with the Folio's King Lear – very different from the quarto version – is still a subject of ferocious debate.

What is Shakespeare's writing like?

Judging by what's almost certainly the only manuscript by him we have, a single scene from an unpublished play about Sir Thomas More, Shakespeare didn't have especially neat handwriting, and spelled in a freestyle fashion, even for the time. He was also fond of unusual words. In the circumstances, the printers didn't do too badly, but they still made a lot of blunders. In the Folio's Richard II, "White Beares" rise up against the king. The printer was presumably aiming for "white beards" – old men. There are many mistakes of this sort. Foreign words gave them particular trouble – the Folio's Coriolanus wears a "tongue" instead of a "toga" – and one printer, known only as "Compositor B", is thought to have been prone to rewriting lines when he couldn't follow Shakespeare's drift.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

How did the book do?

The First Folio seems to have sold out, to high-status men: they cost 15 shillings unbound, 20 shillings bound (the price of more than 40 loaves of bread). Its success led to the Second Folio in 1632, which removed many errors and added further plays. The Bodleian Library in Oxford sold its First Folio after the Third came out in 1663. In 1905, it bought it back for around £450,000 in today's money. During the 18th century, Shakespeare had gone from being an admired old playwright to being the national poet; and the Folio became "the holy book of a new secular religion, bardolatry", as one scholar puts it. By 1793, the First Folio was described as "the most expensive single book in our language" and prices have only gone up ever since. In 2020, Christie's sold a First Folio for a record $9.98m.

Where are they all now?

Of an estimated 750 copies printed, there are 235 known survivors, making First Folios reasonably abundant by the rare books trade's standards. In the 19th century, they started migrating west, having become a status symbol for American millionaires. Henry Clay Folger, president of Standard Oil, bought 79 of them between 1893 and 1928. As a result, there are now 149 in the US, compared with 50 in the UK; 82 are in the Folger Shakespeare Library, in Washington, the global centre of Shakespeare studies. There are 12 at Meisei University in Japan; the British Library has five. As the book that introduced Shakespeare to the world, it is, like Gutenberg's Bible, one of history's most famous volumes. It made Shakespeare, as Ben Jonson put it, "not for an age, but for all time".