Lula and the world: what to expect from new Brazilian foreign policy

As Brazil’s new president kicks off his third term, foreign policy will be a tool for building his own domestic political legitimacy

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Guilherme Casarões, professor of political science at the São Paulo School of Business Administration explains how Jair Bolsonaro's successor must restore Brazil’s activism at the United Nations and balance Brazilian relations between Beijing and Washington if his third term is to be a success.

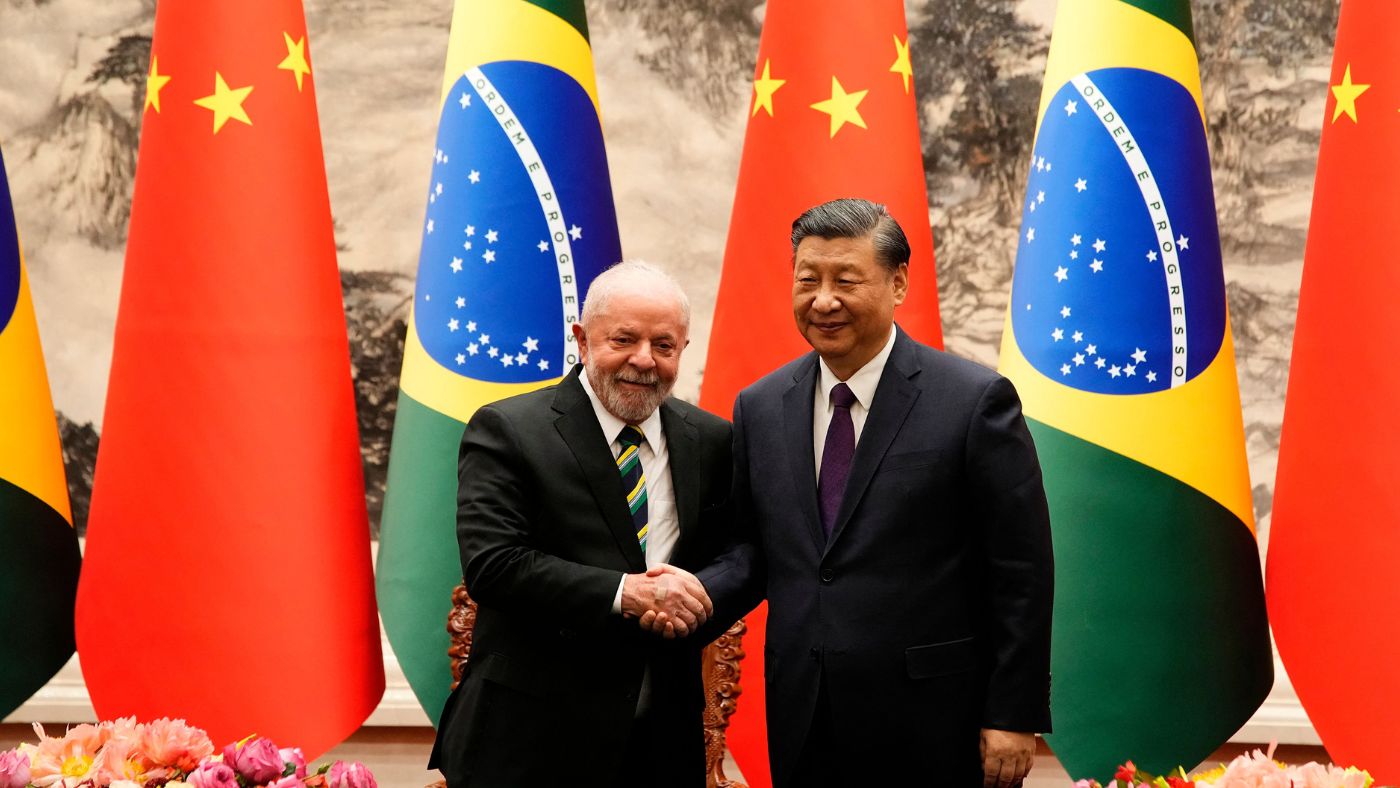

Brazilian president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva was scheduled to visit his Chinese counterpart, Xi Jinping at the end of March. Beijing would have been Lula’s fourth international destination in less than 100 days in office.

Lula had to cancel his trip, which was set to include 200 business people, after catching pneumonia but it is now expected to take place in April or May. His administration had hoped the China visit would alleviate political pressure at home.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Since returning to the presidency (his previous term was 2003-2010), Lula has already been to visit partners in the South American trade bloc Mercosur, Argentina and Uruguay, and recently flew to Washington DC for conversations with US president Joe Biden and members of the Democratic party over infrastructure investments, trade and climate change.

Globetrotting seems like quite an effort for a 77-year-old, third-term president who faces a deeply divided society. But Lula does it with a smile on his face. Since he first took office 20 years ago, the former metalworker has risen to the challenge of international diplomacy as a natural negotiator with political charm.

Building political legitimacy

As Lula kicks off his third term, foreign policy will be a tool for building his own domestic political legitimacy. His reputation currently appears to be greater abroad than at home.

Always a determined player on the international stage, Lula’s administration spearheaded the construction of Unasur, a South American organisation set up to offset US economic and political power in the region. He also forged several alliances in the developing world.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Although Lula left office in 2010 with an impressive 83% approval rating, much of his political capital waned in the years that followed. This was largely thanks to his successor Dilma Rousseff’s pitiful economic performance and to the mounting accusations of graft against top figures in his Workers’ party.

But despite being indicted and imprisoned for corruption in early 2018 (at which point his domestic popularity plummeted), the admiration of foreign figures has endured. Some even visited Lula in prison, protesting what they called political persecution of the former president.

So, at the age of 77 – and with health problems – a big diplomatic play might be his best bet of leaving a presidential legacy.

Challenges of a new world order

But Brazil’s capacity as a meaningful international player will depend on the administration’s ability to navigate a world that is fundamentally different from the one of the early 2000s.

The country is not in its best shape, either. In the years following Lula’s first two terms, Brazil went through a decade of decline, introspection and isolation.

Much of this is down to his immediate predecessor, Jair Bolsonaro. On Bolsonaro’s watch, Brazil ranked second, at 700,000 recorded deaths, in total COVID fatalities. Massive areas of rainforest were burned, and the lands of the Yanomami indigenous people were devastated by large amounts of mining.

So, while Lula must capitalise on any residual international popularity to relaunch Brazil as a global player, he has a lot to do to restore his own country’s economy and to heal the wounds of a divided society.

Lula’s first task internationally – a tough challenge – is to strike a balance in his relationships with Washington and Beijing, Brazil’s two foremost partners. So far, his new administration’s even-handed strategy has worked fine. But if tensions between Joe Biden and Xi Jinping lead to further political instability – or if a Republican with a zero-sum approach to China gets elected in 2024, Brazil could find itself in a difficult position.

Lula has attempted to anticipate these problems by offering to broker peace between Russia and Ukraine. It was a way to dodge criticism by western powers, who wanted Brazil to engage in military assistance to the Ukrainian government – while still preserving Brazil’s longstanding ties with Russia.

Lula’s take on the war is part of what researchers have dubbed “active non-alignment”. It is part of a broader Latin American strategy to safeguard policy space and instruments for national development strategies in an increasingly polarised international order. By offering itself as a high-profile mediator, Brazil wants to maintain trade and cooperation with all sides in the conflict.

Lula’s balancing trick

But Russian-Ukrainian peace appears to be a long way off – and it will hardly come via mediators from the developing world. If Lula wants to create a legacy, he needs to build on Brazil’s preexisting capacity, in both multilateral and regional terms.

One possible way is to restore Brazil’s activism at the United Nations. He must also reestablish cooperation in issues as diverse as climate change, biodiversity, indigenous rights, vaccines, food security and development.

Another way is to rebuild South American integration. Regional organisations such as Mercosur and Unasur could help bolster global supply chains in critical sectors like energy and food that have been disrupted by the war in Ukraine. To do so, Brazil must reclaim its role as the continent’s centre of economic gravity.

But there is an obstacle: Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro. A persistent political, economic and humanitarian crisis in Venezuela has exposed the dangers of left-wing authoritarianism. Lula is one of the few leaders who have open channels with Maduro and may be able to help the country work towards a national reconciliation.

The question is whether Lula wants to get involved. Unlike left-wing leaders who recently rose to power in Chile and Colombia, Lula and the Workers’ party have been unapologetically sympathetic towards dictators such as Venezuela’s Maduro and Nicaragua’s Daniel Ortega.

Overcoming the Brazilian left’s outdated views on authoritarian socialism and anti-imperialism may be as daunting a challenge for the Lula administration as leaving a sound diplomatic legacy. But both steps are necessary if Lula really wants to make a difference in the region – and the world.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

-

Antonia Romeo and Whitehall’s women problem

Antonia Romeo and Whitehall’s women problemThe Explainer Before her appointment as cabinet secretary, commentators said hostile briefings and vetting concerns were evidence of ‘sexist, misogynistic culture’ in No. 10

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

'Dead' woman nearly suffocated in morgue bag

'Dead' woman nearly suffocated in morgue bagTall Tales And other stories from the stranger side of life

-

Bull gores the ‘Messi of matadors’

Bull gores the ‘Messi of matadors’feature And other stories from the stranger side of life

-

Jenin and the endless cycle of Palestinian displacement

Jenin and the endless cycle of Palestinian displacementfeature Refugee camp at the heart of a struggle around demographics, displacement and mobility

-

Brazil's Bolsonaro banned from holding public office until 2030

Brazil's Bolsonaro banned from holding public office until 2030Speed Read

-

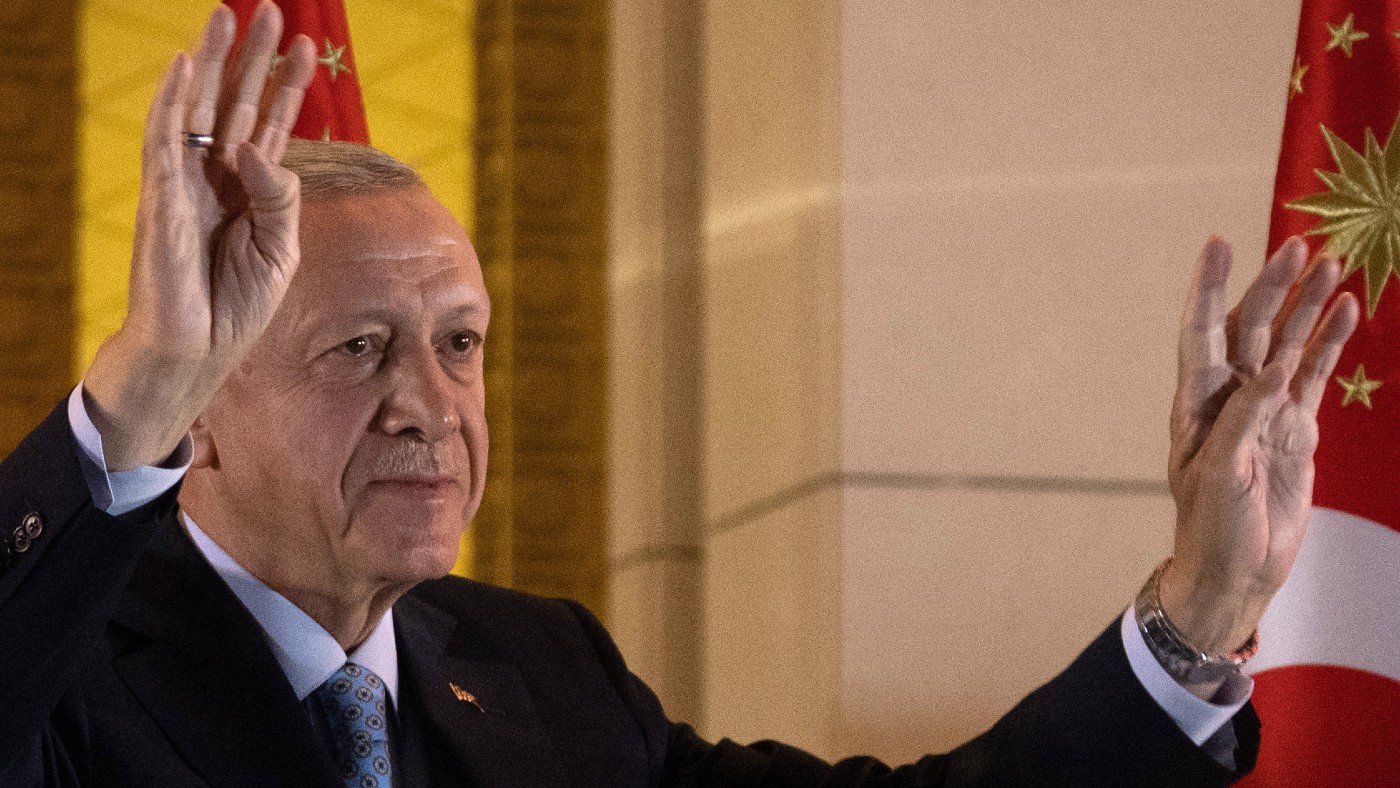

How Erdogan held onto power in Turkey and what this means for the country’s future

How Erdogan held onto power in Turkey and what this means for the country’s futurefeature Staunch support from religious voters and control of the media ensured another five-year term for Turkish president

-

Friend or foe: can the West rely on Lula’s support in Ukraine?

Friend or foe: can the West rely on Lula’s support in Ukraine?Today's Big Question Brazilian president causes consternation among Kyiv’s Western allies by suggesting the war in Ukraine was not solely down to Russia

-

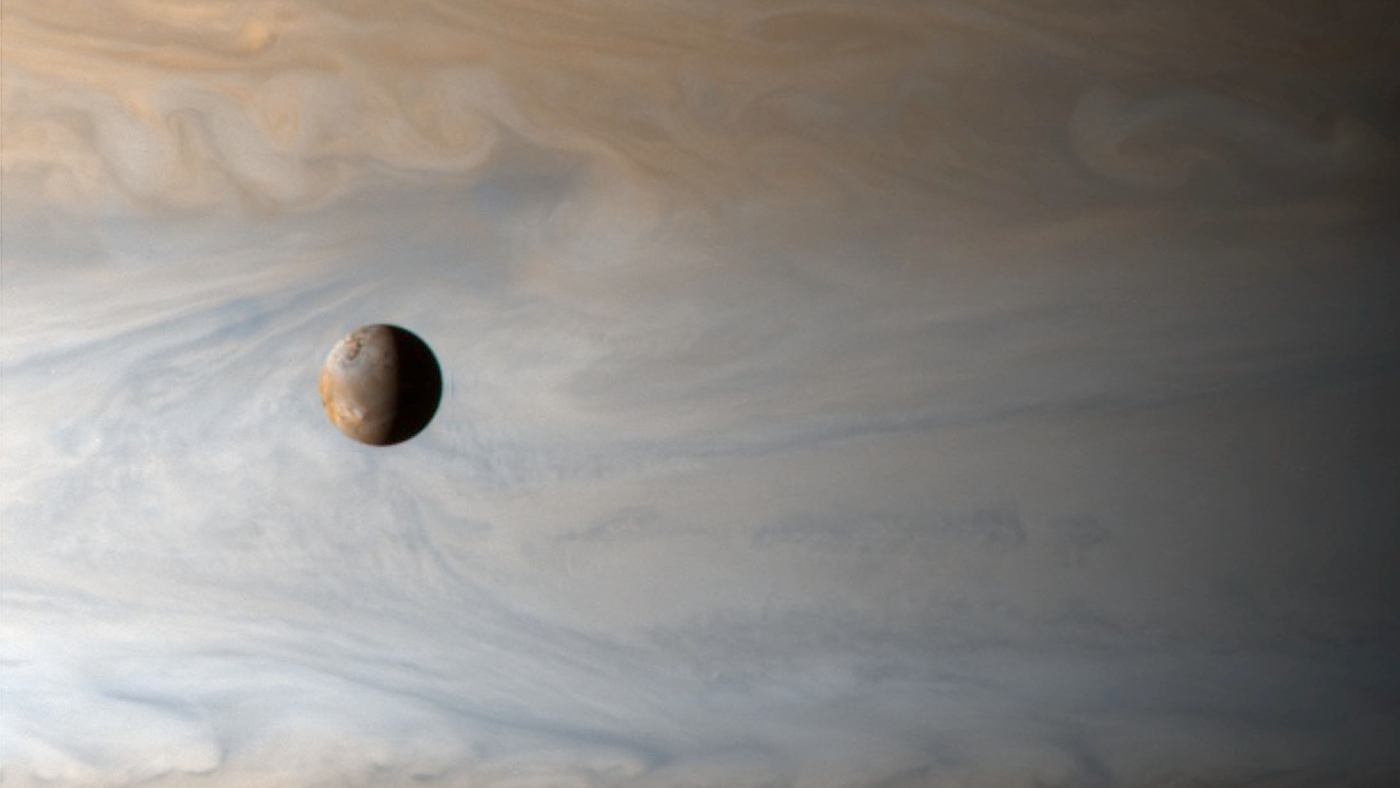

Juice: the European space mission to find life on Jupiter’s moons

Juice: the European space mission to find life on Jupiter’s moonsfeature Three of Jupiter’s moons are home to large, underground oceans that could support life

-

Swimming pools vs. wild swimming: which is worse for germs?

Swimming pools vs. wild swimming: which is worse for germs?feature A microbiologist explores where’s cleanest for a dip: swimming pools, or rivers, lakes, canals and the sea?