The breakup of the United Methodist Church

By the end of 2023, the United Methodist Church will be significantly less united. Here's why.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

By the end of 2023, the United Methodist Church will be significantly less united, torn asunder by a host of issues but mostly over how to address same-sex marriage and gay clergy. Schism over LGBTQ issues is a well-trodden path for mainline Protestant denominations, and the United Methodists have taken some lessons from the Episcopalians, Presbyterians, and Lutherans. Here's a look at the breakup of the United Methodist Church, why it matters, and where it fits in American Christianity.

What is happening with the United Methodist Church?

United Methodists have been more or less civilly disagreeing about gay rights since the 1970s, but the issue came to a head in 2019. At a UMC General Conference that year, the theologically conservative camp, aided by socially conservative United Methodists from Africa, outflanked the moderates and liberals and pushed through a resolution affirming existing UMC bans on same-sex weddings and the ordination of "self-avowed practicing homosexuals" as clergy.

The General Conference also approved a new church law, Paragraph 2553 of the Book of Discipline, offering UMC churches a path out of the United Methodist Church with their church buildings and property — if they get approval from two-thirds of their congregation, sign-off from their regional governing body, and pay their fair share of clergy pension liabilities and two years of "apportionments" for the larger denomination. That temporary exit strategy expires at the end of 2023.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

An ideologically diverse group of UMC leaders crafted a more enduring plan for an amicable divorce — a "Protocol of Reconciliation and Grace Through Separation" — in January 2020, to be approved a the General Conference assembly later that year. "But then COVID arrived, and the convention was postponed three times, to 2024," Mark Tooley, a traditionalist United Methodist, writes in The Wall Street Journal. Those delays "left many traditionalists feeling betrayed and exasperated."

They started heading for the exits. One group formed the theologically conservative Global Methodist Church in May 2022. "Backers of the new denomination have been recruiting United Methodist churches to join since then," United Methodist News notes.

How big is the schism?

The full extent won't be known until the end of 2023. But between 2019 and July 2023, about 6,180 Methodist ccongregations successfully disaffiliated from the UMC, mostly in the South and Midwest. The approved departures represented about 20 percent of America's United Methodist churches in 2019. As of December 2022, the UMC was still the third-largest denomination in the U.S., after Roman Catholics and Southern Baptists, UM News reported.

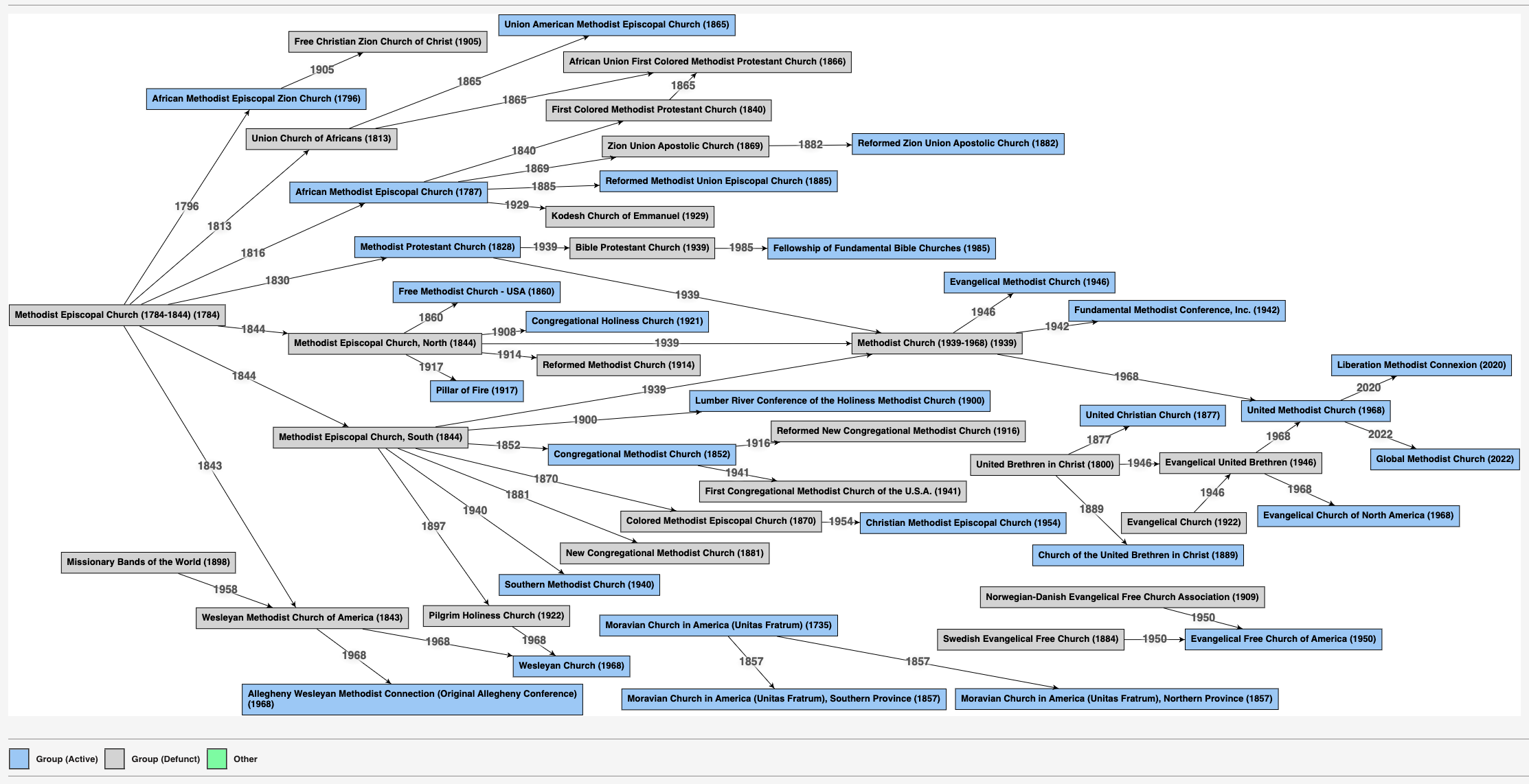

This isn't Methodism's first fracturing. The United Methodist Church formed in 1968 from the union of Methodist denominations that split over slavery in the 1800s. The Association of Religious Data Archives (ARDA) pieced together a Methodist family tree, starting with the Methodist Episcopal Church, which broke off from the Church of England in 1784.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

What happened in the other mainline Protestant churches?

The Episcopalians, Lutherans, and Presbyterians also lost churches over LGBTQ issues. In each case the more theologically conservative church broke from the main denomination, Heather Hahn explains at UM News, and the main denominations have since expanded their embrace of gay and lesbian members.

With the Episcopal Church, the breakup began when the New Hampshire diocese elected and consecrated the first openly gay bishop, V. Gene Robinson, in 2003. After years of tumult, the breakaway Anglican Church in North America split from the Episcopal Church in 2009.

The Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA) lost members after voting to allow pastors to bless same-sex unions and congregations to accept gay clergy in "monogamous" marriages in 2009. The main breakaway factions are the North American Lutheran Church and a looser global network called the Lutheran Congregations in Mission for Christ.

A majority of Presbyterian Church (USA) presbyteries voted in 2011 to open the door to clergy and lay leaders in same-sex relationships. The next year, the first of hundreds of churches broke away, many forming the Evangelical Covenant Order of Presbyterians (ECO) offshoot.

The Lutherans had the cleanest divorce, because the ECLA generally lets churches that leave to join another Lutheran faction keep their property. The Episcopalians, like the United Methodists, hold their property in communal trust. With no equivalent of the UMC's Paragraph 2553, Episcopalians are resolving disputes over ownership of church property in court.

The chief lesson the United Methodists can learn from these other splits is that while "no denominational divorce is easy," all the mainline denominations "are still standing and doing ministry — and so are the new denominations that have struck out on their own," Hahn wrote.

Are these denominational divorces only about gay rights?

Gay marriage and clergy are the brightest "flashpoints" in these schisms. Same-sex marriage in particular has gained acceptance in the U.S. at an astonishingly fast rate, and some religious and cultural conservatives would like to stand athwart this shift. But these issues are also "symptoms for deeper differences in views on justice, theology, and scriptural authority," The Associated Press reports.

Along with clashes over LGBTQ issues, for example, the North American Anglicans oppose the Episcopal Church's ordination of women; ECO claims theological and bureaucratic disagreements with the Presbyterian Church; and breakaway Lutherans disagreed with the ELCA over its decisions to enter into full communion with the United Methodists in 2009 and Episcopal Church in 1999.

Why should non-Christians care about the UMC rift?

What happens in church doesn't always stay in church. "Big church splits can prefigure big national splits," Bonnie Kristian cautioned at The Week. The Baptists, Methodists, and Presbyterians all split over slavery in the decades before the Civil War, and many historians say "those breaks accelerated the severance of social and political ties that made disunion plausible."

"The parallel between then and now is not a perfect one," Joshua Zeitz writes at Politico. "Two-hundred years ago, organized Protestant churches were arguably the most influential public institutions in the United States," and that's no longer true. But "in a country with a shrinking center," he adds, it's worrisome that mainline Protestants can once again no longer absorb the nation's large political and social disagreements.

"We tend to imagine that breaking up churches or other groups who can't agree on political issues will calm things down, keep the peace," Kristian observes. "Instead, they often have an escalatory effect," as battle lines harden.

Updated July 10, 2023: This piece has been updated throughout.

Peter has worked as a news and culture writer and editor at The Week since the site's launch in 2008. He covers politics, world affairs, religion and cultural currents. His journalism career began as a copy editor at a financial newswire and has included editorial positions at The New York Times Magazine, Facts on File, and Oregon State University.

-

Is the 'vibecession' over?

Is the 'vibecession' over?Speed Read The IMF reported that the global economy is looking increasingly resilient. Is it time to start celebrating?

-

The U.S. veterinarian shortage crisis

The U.S. veterinarian shortage crisisSpeed Read With an anticipated shortage of 15,000 vets by 2030, it will be harder to get care for pets

-

Inside Russia's war crimes

Inside Russia's war crimesSpeed Read Occupying forces in Ukraine are accused of horrific atrocities. Can they be held accountable?

-

Is it safe to ride a roller coaster?

Is it safe to ride a roller coaster?The Explainer A pair of startling events have shined a light on amusement park safety

-

World leaders who have been charged or imprisoned

World leaders who have been charged or imprisonedThe Explainer Heads of state being put behind bars is not a rare occurrence

-

The China-Cuba connection, explained

The China-Cuba connection, explainedSpeed Read Reports of an eavesdropping deal roil Washington

-

The future of AM radio in the US

The future of AM radio in the USSpeed Read Automakers that have removed AM radios from new electric vehicles are facing pushback from broadcasters and politicians

-

The persistent inequities of Covid-related learning loss

The persistent inequities of Covid-related learning lossSpeed Read The pandemic set a generation of students back in their education. Can they catch up?