Ukraine blames Russia for destroying major hydroelectric dam 'in panic' as counteroffensive starts

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

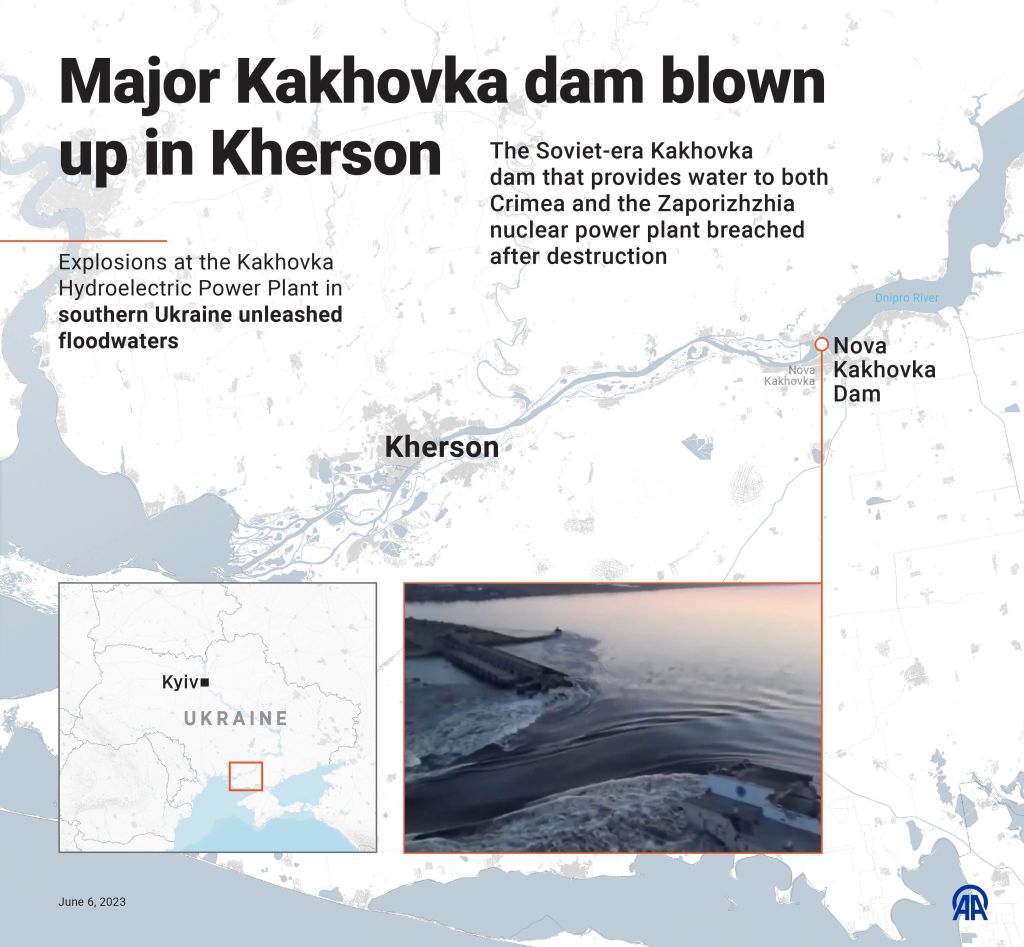

Ukraine accused Russia of blowing up the Kakhovka dam on the Dnipro River early Tuesday, sending a Great Salt Lake's worth of water downstream to flood communities and wreak massive ecological damage in both Ukrainian and Russian-occupied Kherson province. The dam, a major hydroelectric power station and the only Dnipro crossing in the region, has been under Russian control since last year. The Russian-appointed mayor of nearby Nova Kakhovka said overnight shelling caused the dam's collapse, though he did not say whether the shells were fired by Ukraine or Russia.

Ukraine said 16,000 civilians on the West side of the river, which it controls, are at critical risk from flooding. The Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant upstream is also in eventual danger as it uses water from the draining Kakhovka Reservoir to cool the plant's six reactors, which have been in cold shutdown mode for months. The Kakhovka dam power station, ruined beyond repair, provided electricity to three million people.

"Russian terrorists," Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy wrote on Telegram. "The destruction of the Kakhovka hydroelectric power plant dam only confirms for the whole world that they must be expelled from every corner of Ukrainian land." Russian occupiers "blew up the Kakhovka Reservoir dam in panic," Ukraine's Defense Intelligence department suggested. "This terrorist act is a sign of the Putin regime's panic."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The demolition of Kakhovka dam coincided with what Russian and U.S. officials said was the start of Ukraine's long-awaited counteroffensive to reclaim Russian-occupied land. The dam's destruction "could win Russia time to reconfigure its defenses while at the same time depriving Ukraine of some options," The Wall Street Journal noted. Ukraine can now no longer cross the Dnipro along that stretch of the front line, for example, so Russia could redeploy forces in the area to defend sections further north.

But "in the longer term, the flooding could also wash away fortifications put up by Russian forces in the area," the Journal said. And some Russian pro-military bloggers suggested that the lower Dnipro water levels upstream could allow Ukrainian forces to cross into Russian occupied Kherson and Zaporizhzhia. The reservoir also supplied a canal that brought drinking water to Russian-occupied Crimea, and the "devastating consequences" from dam's destruction will include "a decadelong water shortage" on the peninsula, said Mustafa Nayyem, the head of Ukraine's State Agency for Restoration and Infrastructure Development.

European Council president Charles Michel said the "unprecedented attack" on civilian infrastructure "clearly qualifies as a war crime — and we will hold Russia and its proxies accountable." British Foreign Secretary James Cleverly told Reuters from Ukraine that "it's too early to make any kind of meaningful assessment of the details," but "it's worth remembering that the only reason this is an issue at all is because of Russia's unprovoked full-scale invasion of Ukraine."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Peter has worked as a news and culture writer and editor at The Week since the site's launch in 2008. He covers politics, world affairs, religion and cultural currents. His journalism career began as a copy editor at a financial newswire and has included editorial positions at The New York Times Magazine, Facts on File, and Oregon State University.