Scientists have discovered something weird about Jupiter's magnetic field

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

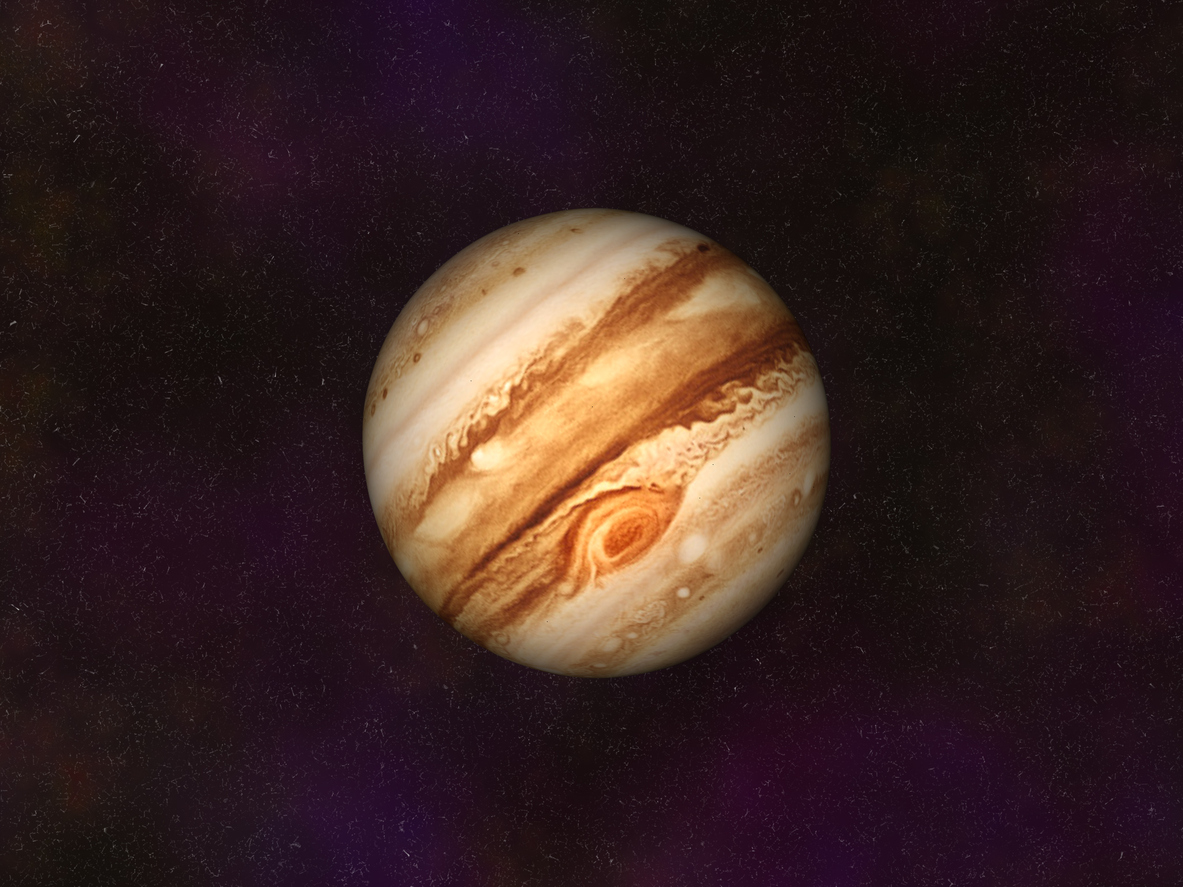

Each planet in our solar system has its own weird quirk — Venus' poisonous atmosphere, Saturn's rings, or Mars' potential to harbor human life. In a new study published in the journal Nature, scientists have discovered something strange about Jupiter as well.

Jupiter, like Earth, has a magnetic field. But unlike Earth's, Jupiter's magnetic field isn't relatively symmetrical. Instead, its northern hemisphere and southern hemisphere have magnetic fields that look nothing alike, Gizmodo reported. Where Earth's magnetic field points pretty much straight up and down, like a bar magnet, Jupiter's magnetic field is more like "someone took a bar magnet, bent it in half, and splayed it at both ends," Science News explained.

"It's a baffling puzzle," said the study's lead author, Harvard Ph.D. student Kimberly Moore. But it might have something to do with the different compositions of Earth and Jupiter. On Earth, the magnetic field is created by the liquid iron that composes part of our planet's core — but we have no idea what Jupiter's core is made of, or if it has anything to do with the planet's magnetic field. Instead, scientists theorize that Jupiter's magnetic field is caused by the presence of metallic hydrogen among its gaseous structure, Sky & Telescope reported.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Scientists still don't know for sure what's causing the strange unevenness of Jupiter's magnetic field, or why it's "so complicated in the northern hemisphere but so simple in the southern hemisphere," Moore said. But they theorize that varying concentrations of this metallic hydrogen might be the underlying cause.

NASA's Juno orbiter, which collected the data used in this study, will continue to monitor the gas giant until 2022. Read more about the project at Gizmodo.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Shivani is the editorial assistant at TheWeek.com and has previously written for StreetEasy and Mic.com. A graduate of the physics and journalism departments at NYU, Shivani currently lives in Brooklyn and spends free time cooking, watching TV, and taking too many selfies.

-

Antonia Romeo and Whitehall’s women problem

Antonia Romeo and Whitehall’s women problemThe Explainer Before her appointment as cabinet secretary, commentators said hostile briefings and vetting concerns were evidence of ‘sexist, misogynistic culture’ in No. 10

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

Rubio boosts Orbán ahead of Hungary election

Rubio boosts Orbán ahead of Hungary electionSpeed Read Far-right nationalist Prime Minister Viktor Orbán is facing a tough re-election fight after many years in power

-

Key Bangladesh election returns old guard to power

Key Bangladesh election returns old guard to powerSpeed Read The Bangladesh Nationalist Party claimed a decisive victory

-

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK government

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK governmentSpeed Read Peter Mandelson, Britain’s former ambassador to the US, is caught up in the scandal

-

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishes

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishesSpeed Read The incident comes amid heightened tensions in the Middle East

-

EU and India clinch trade pact amid US tariff war

EU and India clinch trade pact amid US tariff warSpeed Read The agreement will slash tariffs on most goods over the next decade

-

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from Gaza

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from GazaSpeed Read The 24-year-old police officer was killed during the initial Hamas attack

-

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purge

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purgeSpeed Read Zhang Youxia is being investigated over ‘grave violations’ of the law

-

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mine

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mineIn the Spotlight Panama is set to make a final decision on the mine this summer