Returning the Crown Jewels

The objects and gemstones are said to be of 'incalculable cultural, historical, and symbolic value'

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

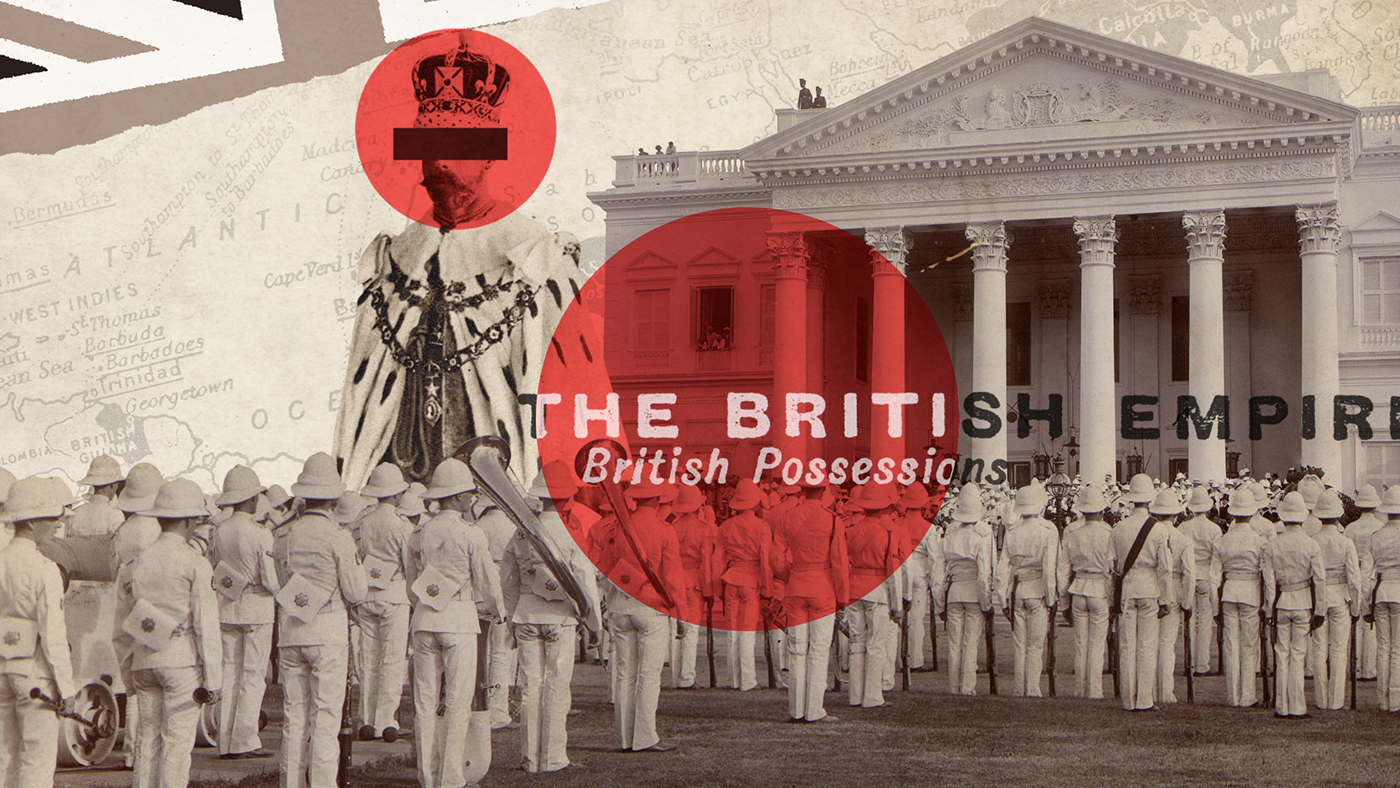

With the death of Queen Elizabeth II after a 70-year reign, many believe this is the time for change. Some are seeking an end to the monarchy, while others have their sights on something more tangible: the Crown Jewels. There are many who see these priceless artifacts as symbols of an imperialist past, and believe they should be returned to their places of origin, including South Africa and India. Here's everything you need to know:

What are the Crown Jewels?

The Crown Jewels are made up of more than 100 objects and over 23,000 gemstones, acquired over centuries by kings and queens. Historic Royal Palaces describes the Crown Jewels as "priceless, being of incalculable cultural, historical, and symbolic value," with the St. Edward's Crown the "most important and sacred of all the crowns," used just at the moment of crowning during a coronation. This crown dates back to 1661, with a solid gold frame that weighs almost 5 pounds. The Crown Jewels are stored and displayed at the Tower of London, and are part of the Royal Collection, held in trust by the monarch.

What are the most famous jewels in the collection?

The Imperial State Crown, made in 1937 for the coronation of King George VI, is worn by the monarch during state occasions, making it much more visible and well-known than the St. Edward's Crown. It sparkles thanks to its 2,868 diamonds, 269 pearls, 17 sapphires, 11 emeralds, and four rubies. Some of these jewels are famous in their own right, like the Cullinan II Diamond, Stuart Sapphire, and Black Prince's Ruby, which is actually a semi-precious stone called a balas. The Cullinan II Diamond is 317.4 carats, and the second-largest stone cut from the 3,106-carat Cullinan Diamond.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Where did these jewels come from?

Some of the jewels were gifts — in 1907, the uncut Cullinan Diamond was presented to King Edward VII on his 66th birthday by the Transvaal government, which was under British rule. Historic Royal Palaces says this was "intended to symbolize good relations between England and South Africa after the South African War."

However, the history behind this diamond and many others in the Crown Jewels is not that simple. The Cullinan I, or the Great Star of Africa, was cut from the Cullinan Diamond, and is mounted on the top of the Sovereign's Scepter, which was seen on Queen Elizabeth's coffin. Because the diamond was given to Edward VII by colonial authorities, many South Africans think the jewel should be returned and put on display in the country. Speaking to local media, activist Thanduxolo Sabelo said the "minerals of our country and other countries continue to benefit Britain at the expense of our people," while Vuyolwethu Zungula, a member of parliament, encouraged his fellow South Africans to "demand reparations for all the harm done by Britain" and "demand the return of all the gold, diamonds stolen by Britain."

It doesn't matter that the Transvaal government purchased the Cullinan, because "colonial transactions are illegitimate and immoral," University of South Africa Prof. Everisto Benyera told CNN. "Our narrative is that the whole Transvaal and Union of South Africa government and the concomitant mining syndicates were illegal. Receiving a stolen diamond does not exonerate the receiver. The Great Star is a blood diamond."

What other jewels do people think should be returned?

The massive, 105-carat Kohinoor diamond, which was mined in India, most likely in the 13th century. The Kohinoor made its way from dynasty to dynasty in Pakistan, Iran, and Afghanistan before being obtained by the Sikh Maharaja Ranjit Singh in 1813. His son and successor, Maharaja Duleep Singh, signed the Treaty of Lahore in 1849 after the annexation of Punjab, when he was just 11 years old. As part of the treaty, the Kohinoor was ceded to Queen Victoria. Today, the Kohinoor is the biggest jewel on the Queen Mother's Crown, and remains one of the world's largest cut diamonds.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Danielle Kinsey, an assistant professor of history at Carleton University in Ottawa, told NBC News the diamond "has a history of being part of war booty or trophies taken as the result of war in South Asia. So, in a lot of ways, it is a symbol of plunder and represents the long history of plunder imperialism." After the Treaty of Lahore was signed, India's governor-general, Lord Dalhousie, wrote to a friend that he pressured Duleep to "gift" the Kohinoor to Queen Victoria, and he "had visions of it becoming the centerpiece of the British imperial crown and had visions of himself becoming famous for facilitating the crown's appropriation of the stone," Kinsey said.

Shashi Tharoor, a member of parliament in India, said having the diamond on public display in the Queen Mother's Crown is "a powerful reminder of the injustices perpetrated by the former imperial power. Until it is returned, at least as a symbolic gesture of expiation, it will remain evidence of the loot, plunder, and misappropriation that colonialism was really all about."

Could these jewels be returned to their countries of origin?

Yes, there is no reason why they couldn't be returned. However, it should be noted that the British government has said before that in its view, there is no legal ground for restitution of the diamond. No one in the British royal family has said anything about giving jewels back to their countries of origin, but Kinsey told NBC News she believes that in the case of the Kohinoor, "at some point, the monarchy will understand that keeping the diamond is more of a public relations liability for them than an asset." There are "many, many looted artifacts in Britain today," she continued, and returning objects with colonial ties is "the right thing to do if the royal family is serious about making apologies for the ills of British imperialism and how they profited from it."

Afua Hagan, a royal commentator for CTV News, said this is a new era for the monarchy, and it's the perfect time for King Charles III and his heir, Prince William, to "look at the royal family's colonial past and the riches acquired by that and whether those items have a place in their realm's multicultural future. Returning jewels and artifacts to where they belong is a good place to start."

Catherine Garcia has worked as a senior writer at The Week since 2014. Her writing and reporting have appeared in Entertainment Weekly, The New York Times, Wirecutter, NBC News and "The Book of Jezebel," among others. She's a graduate of the University of Redlands and the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Pros and cons of British colonial reparations

Pros and cons of British colonial reparationsfeature Should the U.K. be forced to pay for its historic subjugations?

-

Everything you need to know about King Charles' coronation

Everything you need to know about King Charles' coronationSpeed Read Buckingham Palace says King Charles' coronation will "reflect the monarch's role today and look towards the future"

-

10 things you need to know today: January 29, 2023

10 things you need to know today: January 29, 2023Daily Briefing Memphis police disband Scorpion Unit after fatal beating of Tyre Nichols, Israel seals off home of Jerusalem synagogue attacker, and more

-

Prince Harry says Buckingham Palace is behind 'heinous' articles about him and Meghan

Prince Harry says Buckingham Palace is behind 'heinous' articles about him and MeghanSpeed Read

-

The North Korean nuclear threat, explained

The North Korean nuclear threat, explainedSpeed Read Why does Kim Jong Un need an atomic arsenal?

-

What's next for King Charles?

What's next for King Charles?Speed Read After 10 days of national mourning for the queen, the United Kingdom moves forward with a new monarch at the helm

-

Inside the queen's funeral

Inside the queen's funeralSpeed Read A final goodbye to the beloved monarch who reigned for 70 years

-

Should the British monarchy continue?

Should the British monarchy continue?opinion The sharpest opinions on the debate from around the web