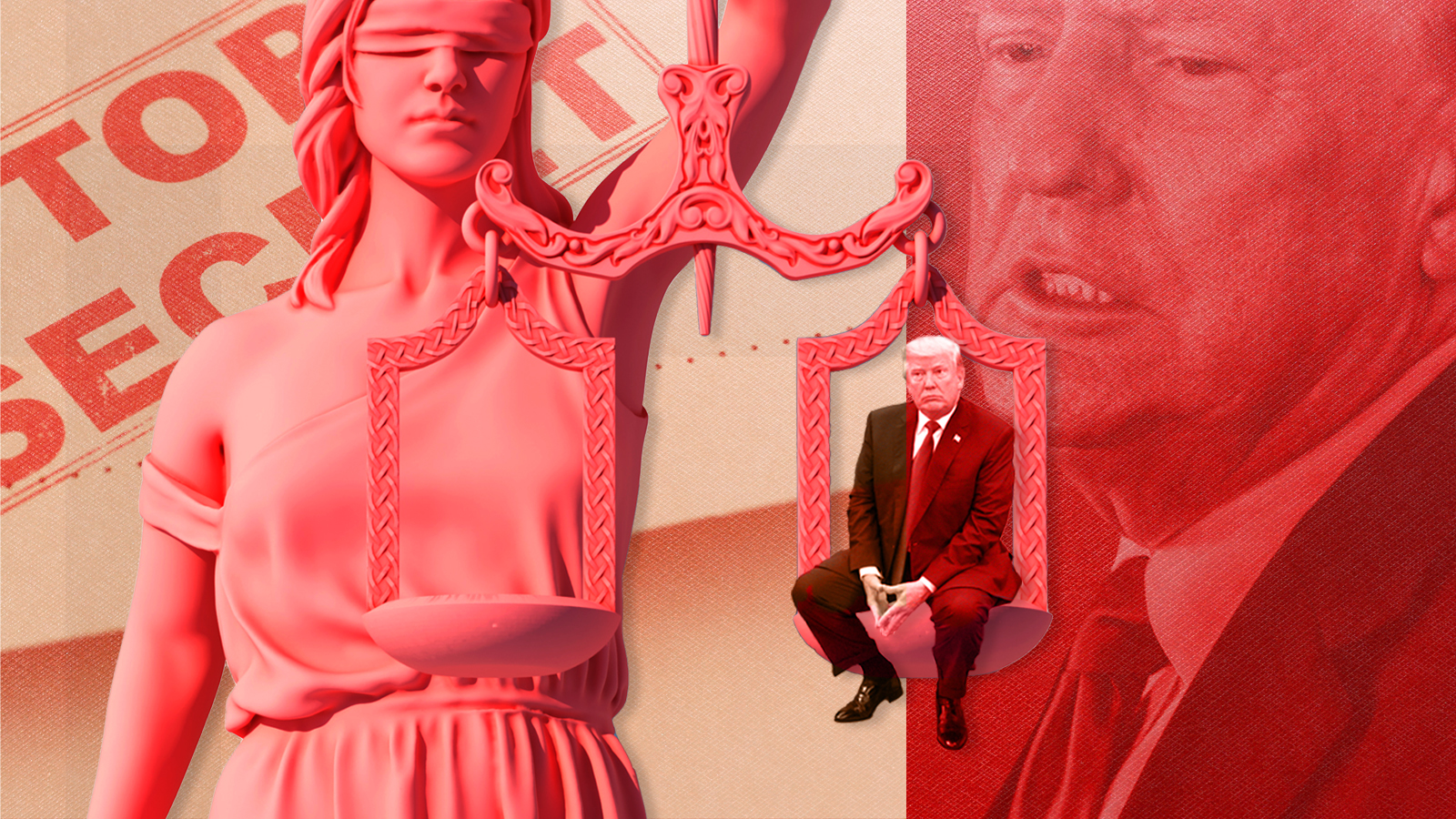

3 extraordinary ways Trump could avoid punishment in Mar-a-Lago documents case

The former president faces real legal peril in the DOJ's classified documents case, but he may once again get lucky

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The case against former President Donald Trump, as laid out in the Justice Department's indictment on 37 counts of "willfully" and carelessly hoarding military secrets and obstructing the government's attempts to get them back, is "very, very damning," as former Attorney General William Barr assessed on Fox News. "If even half of it is true, then he's toast." But even if special counsel Jack Smith has Trump dead to rights legally, that doesn't mean the former president is necessarily heading to prison.

Trump has been the subject of legal complaints and challenges since the early 1970s, and through some combination of wealth, wile, bravado, determination, shamelessness and luck, he has avoided ruination, incarceration and expulsion from office. Smith's classified documents case isn't the only legal threat Trump faces as he seeks a second term in office, but it's so far the most serious. It could conceivably fall apart under scrutiny. But regardless of the case's merits, these are three ways Trump may once again get the better of the justice system.

1. Friendly judge

Out of the gate, Trump "seemed to win the judicial lottery" when, "in an apparently random twist of fate," his case "landed before U.S. District Court Judge Aileen Cannon," one of his appointees and "favorite judges," Politico reported.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Cannon oversaw Trump's earlier attempt to derail the case by contesting the FBI's seizure of documents from his Mar-a-Lago club. "Legal experts described Cannon's pro-Trump rulings at the time as audacious and even lawless, and a conservative appeals-court panel (which itself consisted of two other Trump appointees) quickly overruled her," Politico added. "Now, Cannon will be in an even more powerful position to steer Trump's legal fortunes." Some legal experts have argued for her recusal or reassignment from the case.

There are several ways Cannon could steer the case to Trump's advantage, up to and including unilaterally acquitting him on any or all of the 37 counts under Rule 29 of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure. After the prosecution and defense present their cases, Trump's lawyers could ask for a Rule 29 acquittal and Cannon could agree, essentially asserting that no reasonable jury could find the plaintiff guilty under the evidence presented at trial. If she acquitted Trump before handing the case to the jury, The New York Times reported, "that outcome would be final and prosecutors could not appeal it."

Cannon would also have subtler ways to shape the trial, including deciding when to hold the trial, what evidence is admissible in court, what classified documents are made public, and who sits on the jury, among other rulings. "There are so many 'little' things she can do without any real oversight that can have significant substantive impact on how this prosecution plays out," national security lawyer Mark Zaid told Politico.

Trump's lawyers are expected to file a flurry of pretrial motions to derail or delay the case, and Cannon will have first crack at rejecting or approving the motions. Trump's team has already suggested it will seek to bar damning evidence and accuse the Justice Department of selective prosecution and prosecutorial misconduct. "It is routine for defendants to make such claims, and it is routine for judges to briefly look at and reject them," the Times noted. But that would be up to Cannon.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

"If she were to grant a motion to suppress the evidence obtained in the search, for example, that would really gut the case," said Barb McQuade, a former U.S. attorney from Eastern Michigan. "Similarly, she could suppress the testimony of Evan Corcoran, making her own independent decision that the crime-fraud exception does not apply in this case."

U.S. District Judge Beryl Howard in Washington, D.C., ruled that prosecutors could force Corcoran, a former Trump lawyer, to cooperate because Trump's communications with him had likely furthered a crime. "But Judge Cannon is not bound by Judge Howell's decisions when it comes to what information should be presented to a jury," the Times said. The Justice Department would be able to appeal unfavorable rulings, but it would cost them time.

Finally, if a jury did convict Trump, Cannon would also "impose the sentence," McQuade told Semafor. "Because there is no mandatory minimum here, she could sentence Trump to probation or time served, based on his few moments in custody when he was processed before his arraignment." Cannon would be expected to consider similar sentences in deciding Trump's fate, however, Politico said. "While no former president has been charged or convicted of a federal criminal offense, many people have faced prosecution under the Espionage Act and for obstruction of justice, and many have served significant sentences for those crimes."

2. Hung jury

It would obviously be better for Trump if the jury did not convict him, and some members of his legal team are arguing that "the case is winnable at trial through careful jury selection — one juror is all a defendant needs to convince to avoid conviction," The Washington Post reported.

The jurors will be drawn from Miami-Dade County, which has traditionally leaned slightly Democratic but has "grown more Republican in recent years," the Times stated. That should "offer some comfort" to Trump's lawyers, as should the fact that "many South Floridians, like Americans elsewhere in the country, believe that Mr. Trump is a victim of unfair treatment by powerful forces on the political left."

Prosecutors and Trump's lawyers will have a certain number of discretionary "peremptory" challenges to winnow down the 12 jurors and four alternates, as well as unlimited challenges to disqualify jurors "for cause," typically bias. "Cannon will have the power to accept or reject any 'for cause' challenges, potentially tilting the composition of the jury," the Times reported.

If a judge decides "on cause" challenges "in a one-sided way, it can really put the prosecution in a bind," Joyce Vance, a former U.S. attorney from Alabama, told Politico. "It can force them to spend all of their strikes on prospective jurors, who really should have gone for cause."

Every juror is important, because if all 12 can't decide on a verdict beyond a reasonable doubt, it's a hung jury and a mistrial. "Prosecutors would then have to decide whether to start over with a new trial," the Times explained. Judges typically encourage jurors to reach a consensus, "but if there is an early disagreement, a judge could also kneecap the government by immediately declaring a mistrial."

3. Delay and destroy

Smith has said he will push for a speedy trial, but "Trump has long pursued a strategy of trying to delay legal proceedings against him to run out the clock," the Times reported. Once again, Cannon "is really in the driver's seat in terms of the pacing," retired federal judge Nancy Gertner told the Post. "The danger here is if it backs up into the 2024 campaign or if the case lingers until after Trump is reelected or another Republican elected, and they can direct the Justice Department to drop charges or pardon the president." Trump, if elected, could attempt an unprecedented self-pardon.

In a very real sense, the voters are probably jurors here too. Realistically, "I don't think we'll have this case resolved before the election," Rachel Barkow, a professor at New York University School of Law, told the Times. "And so the election may end up resolving it."

Peter has worked as a news and culture writer and editor at The Week since the site's launch in 2008. He covers politics, world affairs, religion and cultural currents. His journalism career began as a copy editor at a financial newswire and has included editorial positions at The New York Times Magazine, Facts on File, and Oregon State University.

-

Political cartoons for February 21

Political cartoons for February 21Cartoons Saturday’s political cartoons include consequences, secrets, and more

-

Crisis in Cuba: a ‘golden opportunity’ for Washington?

Crisis in Cuba: a ‘golden opportunity’ for Washington?Talking Point The Trump administration is applying the pressure, and with Latin America swinging to the right, Havana is becoming more ‘politically isolated’

-

5 thoroughly redacted cartoons about Pam Bondi protecting predators

5 thoroughly redacted cartoons about Pam Bondi protecting predatorsCartoons Artists take on the real victim, types of protection, and more