The impending cultural disaster in Afghanistan

The last time the Taliban was in power, most art and music was banned or erased

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Osama might be the bleakest film to ever win a Golden Globe, but it wasn't originally supposed to be. When exiled Afghan director Siddiq Barmak started writing the film in Pakistan two years before the overthrow of the Taliban and his eventual return to shoot it in Kabul in 2002, the movie was called Rainbow, and it had a happy ending. "It was not very close to reality," Barmak told Cineaste.

The film — which is not about Osama bin Laden, but about a girl who disguises herself as a boy in order to support her family during the Taliban regime — was notable for being the first movie shot entirely in Afghanistan since the extremists came to power and banned filmmaking in 1996. And while a 2003 movie out of Afghanistan naturally struck a chord with Western critics as a result, winning the Golden Globe for Best Foreign Language Film and getting a rapturous reception at Cannes, it is also a phenomenal and deserving piece of filmmaking, spare and heartbreaking and raw. Though Barmak's Osama wasn't optimistic about the future for girls in Afghanistan, it spelled hope for the nation's film industry, which seemed ready to bounce back.

For many Americans, though, our cultural brushes with Afghanistan have been more limited to The Kite Runner and the final season of Homeland. We've never exactly been a nation that's good at immersing ourselves in international art, but that's especially true when the countries in question lie outside the boundaries of Western Europe. Though mainstream Americans may be familiar with the landscape of Afghanistan through early aughts news reports — or subsequent War on Terror films, where Hollywood-friendly Morocco has often been the stand-in for the Crossroads of Asia — we're very rarely exposed to stories about Afghanistan, told by people who are actually in Afghanistan.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

It might be hard, then, to stir up outrage over the looming cultural loss when there is no Afghan equivalent (to American audiences, anyway) of a Haruki Murakami or a Bong Joon-ho. But despite the stateside stereotypes, "Afghanistan is not only a country of war, destruction, and terrorism, but of life, culture, and art," Omar Sultain, the nation's Deputy Minister of Information and Culture, stressed in 2008 in introduction to a traveling exhibit promoting Afghanistan's "stunningly diverse cultural legacy" to the world.

That legacy was aggressively attacked by the Taliban during their reign from 1996 to 2001 because of the groups' "fundamentalist interpretation of Islam, which forbid paintings depicting living figures," explains Radio Free Europe. "The militia equated portraiture with a blasphemous human attempt to create living objects, something only the supreme deity has the power to do." The ban extended to photography, painting, television, and cinema; additionally dancing at weddings, "un-Islamic" pastimes like kite-fighting or bird-keeping, and nearly all forms of music were likewise forbidden. The Taliban also went on the offensive, burning, bombing, smashing, and rending whatever they could get their hands on. "They succeeded in destroying about 80 percent of our cultural identity," Said Makhtoum Rahim, the Minister of Information and Culture, told The New York Times in 2002.

With the Taliban's return to power, then, comes the dire threat of another gaping period in Afghanistan's cultural history. Already there are rumors of the militants going door-to-door to destroy instruments and beat musicians. Filmmaker Sahraa Karimi, the general director of national film company Afghan Film, shared a desperate open letter to the international community, pleading that "it's a humanitarian crisis, and yet the world is silent … They will ban all art. I and other filmmakers could be next on their hit list." A later video revealed that she'd been detained as the Taliban entered Kabul; later still, she finally shared that she'd somehow managed to make it out of the city "alive and safe." Other artists defiantly soldiered on in their work even as the militants approached, likening their doomed perseverance to the band playing on as the Titanic sank.

The last time the Taliban took power, artists managed to hide and protect some of the nation's cultural treasures — a particularly harrowing story in the case of Afghan Film, where employees risked their lives throwing searchers off the trail of the rarest and most important reels. There's hope now too that with the proliferation of the internet, some art can be uploaded and saved. But while Afghan film digitization efforts have been ongoing since the fall of the Taliban, funding and equipment shortages have slowed the process in recent years. In 2018, the surviving films were relocated from the Afghan Film headquarters to the palace compound in Kabul. "[It] was the only way to ensure they would survive whatever happens next in Afghanistan," The Washington Post wrote in a report at the time. It's unclear how far along in the process the archivists were when the Taliban breached the Afghan presidential palace on Sunday.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

"Archives are the identity of a country," Sultan Mohammad Istalifi, a longtime employee of Afghan Film, stressed to the Post. "If the archive is not preserved, the identity of the country is lost." The historic films further "complicate the picture" of Afghanistan, documentarian Ariel Nasr also explained to the CBC, recalling old footage that shows Afghan women working as soldiers or bus drivers, and giving speeches to large crowds. Another movie tells the story of an Afghan queen who has an affair with a slave. Said Arif Ahmadi, also an employee of Afghan Film, emphasized that "we want our children to learn how Afghans used to live" by having access to the art and stories that came before them.

Equally as haunting, though, is the thought of all the art that won't be created under the incoming regime. Though it's yet unclear how tolerant the Taliban will be this time around, a spokesperson ominously stressed Tuesday that "Afghans have the right to have their own laws, and the world should respect our values." If the second reign of the Taliban resembles the first, there will undoubtedly be stories that won't be told, music that won't be written, and great films like Osama that will remain locked up in private imaginations until the regime falls or loosens again.

That loss is not just Afghans', although it is theirs most immediately and devastatingly. The looming cultural genocide should be mourned by everyone who has ever enjoyed a film or a spontaneous burst of song. All people, regardless of geography and culture, have a fundamental right to artistic creation and self-expression. Indeed, nothing could make us more human.

Jeva Lange was the executive editor at TheWeek.com. She formerly served as The Week's deputy editor and culture critic. She is also a contributor to Screen Slate, and her writing has appeared in The New York Daily News, The Awl, Vice, and Gothamist, among other publications. Jeva lives in New York City. Follow her on Twitter.

-

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on track

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on trackUnder the Radar Swiss watchmaking giant Omega has been at the finish line of every Olympic Games for nearly 100 years

-

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?Today’s Big Question President Donald Trump has recently been threatening the country

-

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the president

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the presidentFeature Trump is at the center of another scandal

-

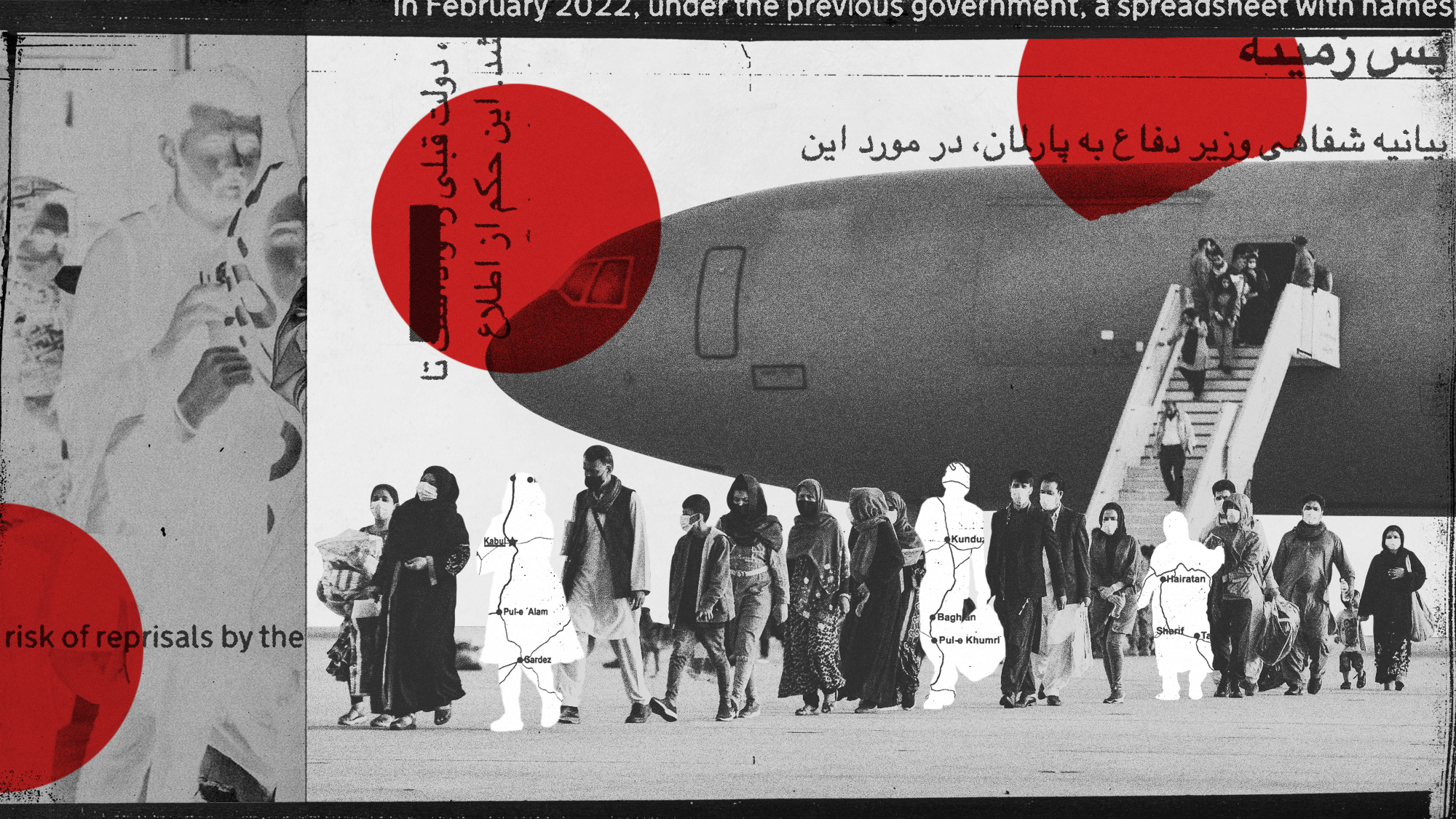

Operation Rubific: the government's secret Afghan relocation scheme

Operation Rubific: the government's secret Afghan relocation schemeThe Explainer Massive data leak a 'national embarrassment' that has ended up costing taxpayer billions

-

The Taliban’s ‘unprecedented’ crackdown on opium poppy crops in Afghanistan

The Taliban’s ‘unprecedented’ crackdown on opium poppy crops in Afghanistanfeature Cultivation in former poppy-growing heartland Helmand has been slashed from 120,000 hectares to less than 1,000

-

Taliban releases 2 Americans held in Afghanistan

Taliban releases 2 Americans held in AfghanistanSpeed Read

-

American detained in Afghanistan for over 2 years released in prisoner exchange

American detained in Afghanistan for over 2 years released in prisoner exchangeSpeed Read

-

Afghanistan: A year after the withdrawal

Afghanistan: A year after the withdrawalopinion What did the U.S. leave behind when it pulled out of Afghanistan?

-

Prominent cleric who supported female education killed in Afghanistan bombing

Prominent cleric who supported female education killed in Afghanistan bombingSpeed Read

-

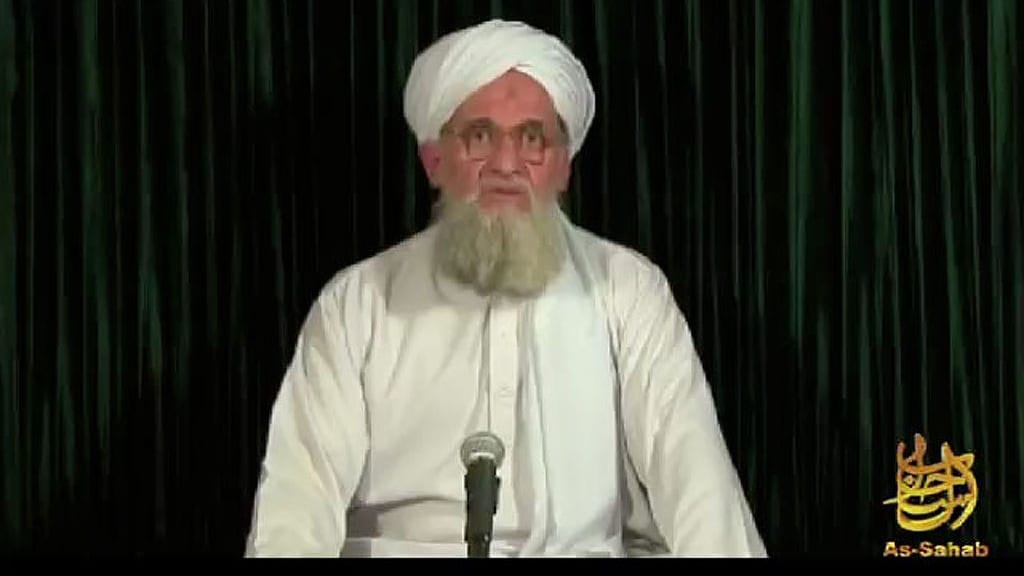

What the U.S. accomplished by killing al-Zawahiri

What the U.S. accomplished by killing al-Zawahiriopinion The sharpest opinions on the debate from around the web

-

Officials: U.S. killed top Al Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri

Officials: U.S. killed top Al Qaeda leader Ayman al-ZawahiriSpeed Read