Could space travel make people live longer?

Zero gravity does strange things to our physiology, and now researchers think it may actually make the body age more slowly

Long space flights are notorious for wreaking havoc on astronauts' bodies, often decreasing the density of bone and muscle. But a new study of zero gravity's peculiar effects conducted by scientists at Britain's University of Nottingham may have given that conventional wisdom a twist, revealing that a species of worms called C. elegans, which are more like humans than you'd think, live longer if they've made a trip to outer space. Here's what you should know:

Why worms?

The slithering creatures are among "the world's most-studied animals" because their bodies deteriorate in a manner similar to ours, says the BBC. C. elegans worms are routinely sent into space, like an outer-space version of a canary in a coal mine, to help scientists study biological changes that astronauts may face later on. The tiny multi-cellular creatures are surprisingly resilient; a few worms even survived the space shuttle Columbia disaster in 2003.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What happened in this experiment?

A small colony of C. elegans was taken on an 11-day journey to the International Space Station and back — a very long trip for an organism with a two- to three-week lifespan. When they returned to Earth, the worms were flash frozen and preserved to study. A control group of worms that had been kept on Earth were thrown into the freezer at the same time.

What happened to the space worms?

They turned out to have lower levels of key genes, some of which may play a role in the aging process. For instance, one gene monitors metabolism, and its lower incidence may potentially help cells work at a less hyperventilating pace. The space worms also had lower levels of certain toxins that build up in aging muscles. After noting these trends, scientists genetically engineered a fresh set of C. elegans to express the same genetic information as their space-traveling counterparts, "and voila," says Colin Lecher at Popular Science: "The worms enjoyed a longer lifespan."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But why?

That remains unclear. But generally, it appears that the worms' bodies sensed shifts in the surrounding environment — in this case, a lack of gravity — that required "changes in metabolism in order to adapt," says lead author Dr. Nathaniel Szewczyk. And "counterintuitively, muscle in space may age better than on Earth." If that's the case, zero-gravity-induced muscle-shrinkage might actually be helpful. Still, says Popular Science's Lecher, "it'll take a lot more research before we name space the 21st Century Fountain of Youth." So don't go booking a flight quite yet.

Sources: BBC, io9, Popular Science, TG Daily

-

Film reviews: ‘Marty Supreme’ and ‘Is This Thing On?’

Film reviews: ‘Marty Supreme’ and ‘Is This Thing On?’Feature A born grifter chases his table tennis dreams and a dad turns to stand-up to fight off heartbreak

-

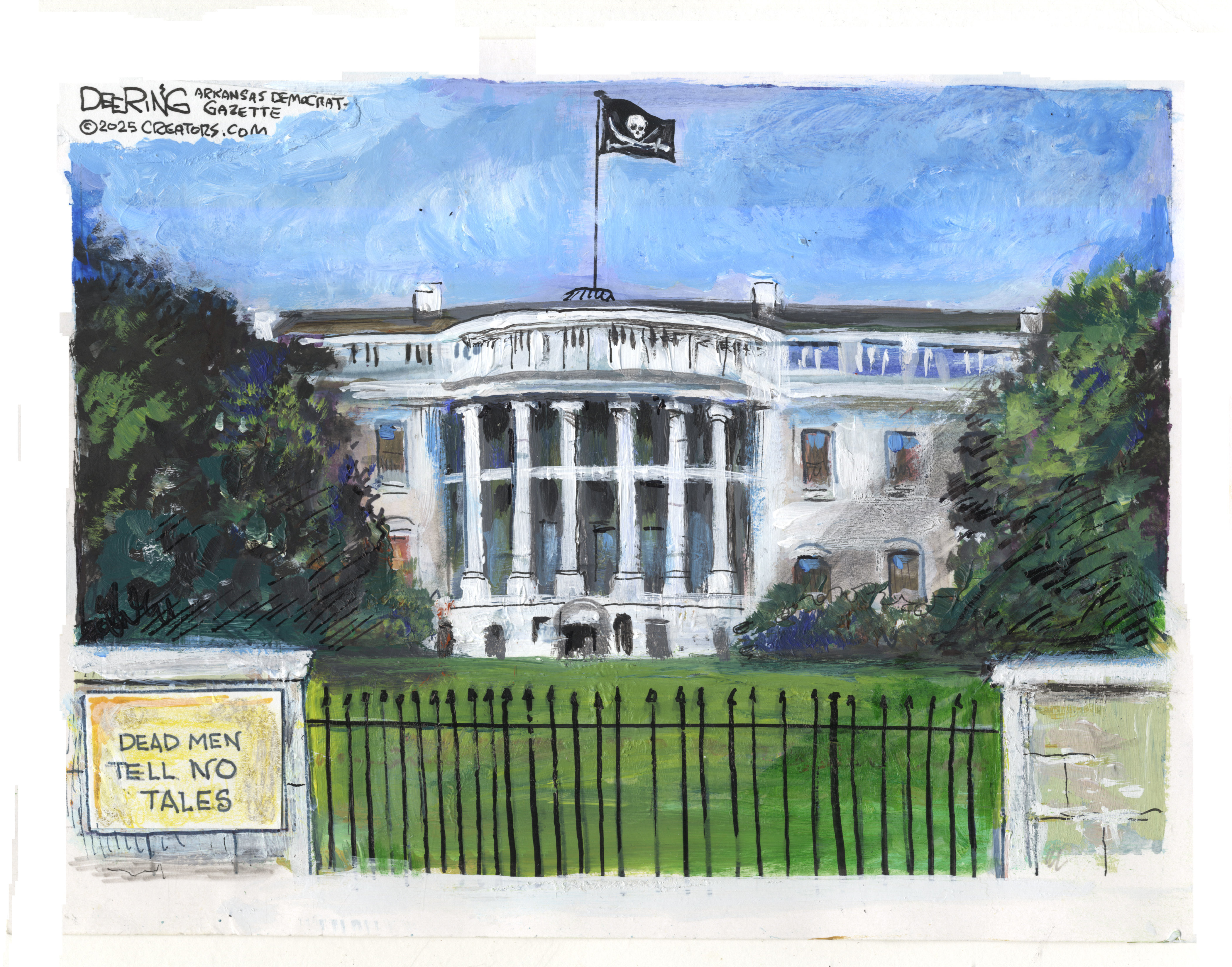

Political cartoons for December 14

Political cartoons for December 14Cartoons Sunday's political cartoons include a new White House flag, Venezuela negotiations, and more

-

Heavenly spectacle in the wilds of Canada

Heavenly spectacle in the wilds of CanadaThe Week Recommends ‘Mind-bending’ outpost for spotting animals – and the northern lights