5 reasons the NSA scandal ain't all that

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

I really do think tribal feelings determine how you view the significance of Edward Snowden's revelations. It is almost impossible not take into account everything associated with the manner that they were released: the dramatic flight to Hong Kong, then Russia; the dramatic differences in press freedoms in the U.S. and U.K.; the detention of David Miranda and the destruction of hard drives inside the headquarters of a newspaper. No matter how hard we try, we can't help but fail to segregate our judgment of the NSA's actions. We want to side with the side we identify with: civil libertarians, journalism, or with the intelligence community, with policy-makers. We accept their assertions and their evidence more than we do the assertions of the "other" side, even though this type of controversy does not lend itself to binary divisions.

I will make the case for why I think the NSA scandal is as bad as it sounds in a future post. Now, I want to make the case, somewhat simplified, that the Snowden revelations, and everything we've learned until this point, do not paint a picture that resembles anything Edward Munch might come up with. I will not qualify any of the reasons below with phrases like, "but of course, they could do much, much better" or "without a doubt, the NSA hasn't been nearly as forthcoming as they ought to be" or "of course Americans have a right to know more." I do believe all of it, and I'll save that for the next post.

1. What NSA does with the metadata it collects on Americans is orders of magnitude less intrusive that what other government agencies do with what they collect, than what companies do with what we give them voluntarily and without our knowledge, or what political campaigns profess to know about you by buying data you did not intend for them to see. It does matter that Americans have no way of knowing whether their number popped up during an analyst's call-chaining session. The daily flow of their lives does not intersect with the NSA's use of the data, so the only mechanism that connects NSA metadata collection with the "chilling" of free speech is the unreasonable expectation that it will, or that it might. Fear itself, in other words, is the biggest threat to our freedoms.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The "privacy rights" that are being violated are very hard to describe in tangible terms. By comparison, when a person is stopped and frisked for no reason other than that he is black — well, I've just described the rights violation and need not say more. The disinclination of critics to articulate the actual harm done by NSA collection, and the inclination to assume facts not in evidence and the worst possible motivations behind those facts, suggests that the scandal is being fed by (real but) disembodied outrage. And this has warped public opinion. The NSA is NOT listening to your phone calls or reading your emails. To say "but they're doing other stuff with it" is a different point. Terms that had meaning, like "dragnet surveillance," are deliberately made elastic to make Americans think that there is a good chance that some analyst somewhere is going to steal the script they've just submitted to an agent. The documents released by Snowden (!) provide ample evidence that this is just not so, almost cannot be so, and indeed, is unlikely to happen without a higher authority finding out about it.

2. Many other government agencies do much more to actively degrade American liberty, and they do so without nearly the degree of oversight that NSA subjects itself to internally and externally. There is no comparison: Getting detained at the border for being a hacker is more viscerally disturbing, and much more traumatic, than knowing that your phone records sit in a database somewhere (or another database, because they already sit in your phone company's database). Conflating the two makes the actual harm seem less harmful. A corollary: The type of information collected by NSA is far less personal than the detailed financial accounting we must provide to the IRS, the medical histories that dozens of Medicare employees see, or even the toll records we provide to state governments when we go over a bridge. To object that metadata analysis could reveal a person's movements and associates in a way that if they knew they were being monitored, they would be less likely to freely associate, one should ground that fear in the reality of a policy or an institutional inclination or a financial incentive. With NSA, these realities are fictitious.

3. Signals intelligence collection is hard to understand, and many, many news outlets, including some of the ones that revealed the documents, came to conclusions that have not stood the test of even a short period of time. No, the NSA does not filter a majority, or even a plurality, or even two percent of the world's internet traffic. The 51 percent relevance test for foreignness does not mean that there is a 49 percent chance that the target might be a U.S. person; it is simply an add-on mechanism to determine where the lines are, precisely so that NSA can stay away from them. Yes, NSA actively audits every search. That's how they know about and report about violations. It is eye-raising to base one's objection to NSA's self-reporting on the idea that there is no way to independently check what the NSA says. Well, of course. There is a logical problem here because someone or some entity will be at the bottom of the chain. It has always been difficult to establish transparent legal and formal mechanisms to make sure that agencies that secretly collect secrets don't abuse their power. But it is easier now than it has ever been. The evidence suggests that NSA has MORE checks on its power now than ever before.

4. The reason why Sens. Ron Wyden and Mark Udall know so much about NSA activities is not because of a whistle-blower. It is because of NSA's evolving self-disclosure. The reason why the intelligence committees defend the programs is because they know how they work, what happens when they don't, and how NSA polices itself. This is not an example of a government agency lacking accountability. This IS accountability. If you begin your assessment of the NSA collection activities with the assumption that all government power is inherently corrosive, you will find ways to describe NSA collection in ways that advance and reify your assumptions.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

5. NSA collects foreign intelligence. Its consumers expect to receive such intelligence. 2010 is not 1970. There just simply isn't a good reason why the NSA would waste its resources on fruitless and voyeuristic domestic collection. From the documents, we learn that the NSA has built in many mechanisms to avoid as much domestic traffic as is technologically feasible. The nut of the case for the NSA's malfeasance is that Americans could be discomforted by the scope of the surveillance state if there were no laws, if American politicians acted like movie politicians, and if NSA employees, many of them active duty members of the military, were inclined to spend time figuring out what their neighbors are doing. The discombobulation we feel in an age where all of us are electromagnetic emitters has nothing to do with NSA, which has to figure out how to decipher it all, but with the evolution of technology and our interactions with it, a state of being that would exist even if the NSA did not.

Marc Ambinder is TheWeek.com's editor-at-large. He is the author, with D.B. Grady, of The Command and Deep State: Inside the Government Secrecy Industry. Marc is also a contributing editor for The Atlantic and GQ. Formerly, he served as White House correspondent for National Journal, chief political consultant for CBS News, and politics editor at The Atlantic. Marc is a 2001 graduate of Harvard. He is married to Michael Park, a corporate strategy consultant, and lives in Los Angeles.

-

The recycling crisis

The recycling crisisThe Explainer Much of the stuff Americans think they are "recycling" now ends up in landfills and incinerators. Why?

-

The L.A. teachers strike, explained

The L.A. teachers strike, explainedThe Explainer Everything you need to know about the education crisis roiling the Los Angeles Unified School District

-

The NSA knew about cellphone surveillance around the White House 6 years ago

The NSA knew about cellphone surveillance around the White House 6 years agoThe Explainer Here's what they did about it

-

America's homelessness crisis

America's homelessness crisisThe Explainer The number of homeless people in the U.S. is rising for the first time in years. What’s behind the increase?

-

The truth about America's illegal immigrants

The truth about America's illegal immigrantsThe Explainer America's illegal immigration controversy, explained

-

Chicago in crisis

Chicago in crisisThe Explainer The "City of the Big Shoulders" is buckling under the weight of major racial, political, and economic burdens. Here's everything you need to know.

-

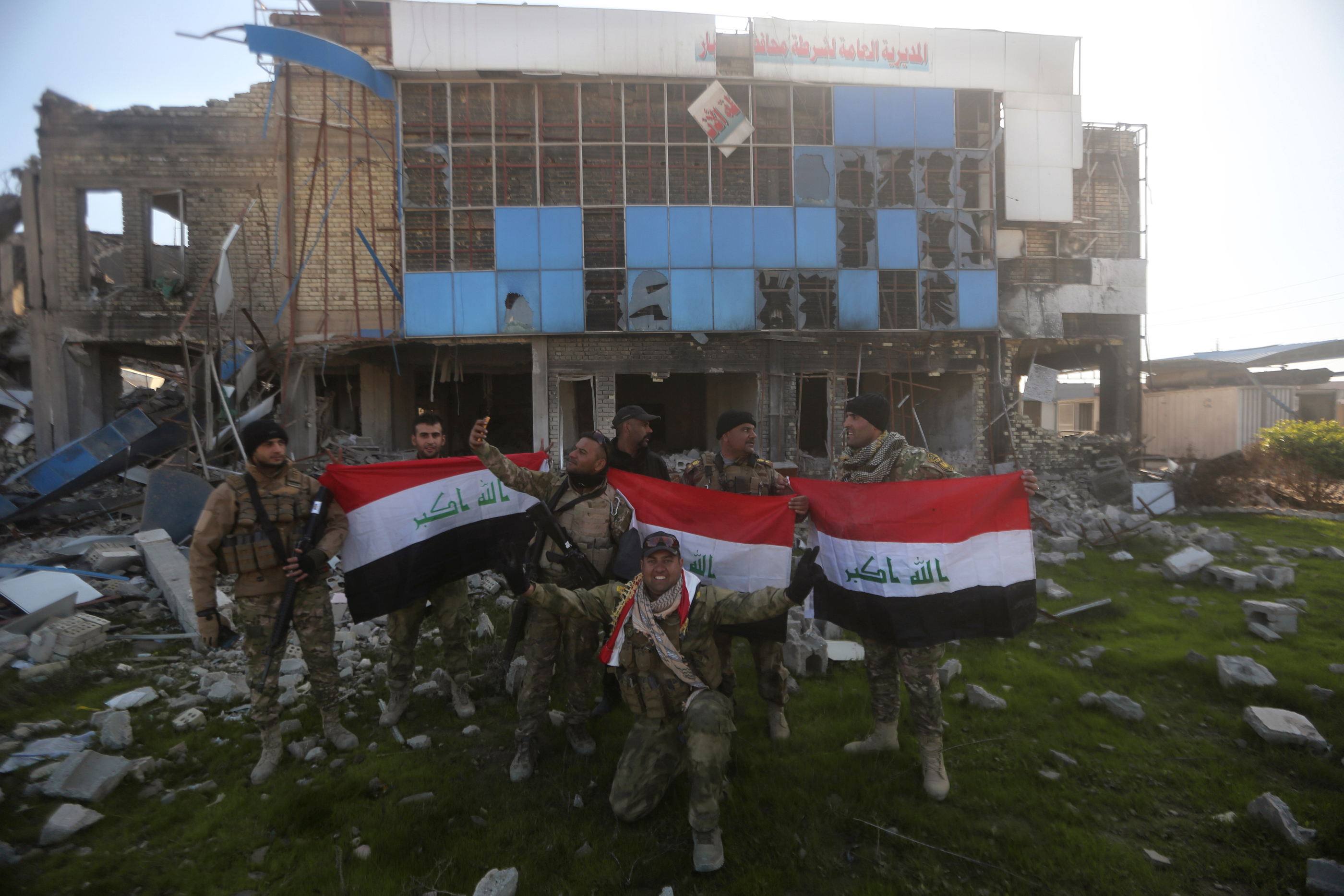

The bad news about ISIS's defeat in Ramadi

The bad news about ISIS's defeat in RamadiThe Explainer The contours of a broader sectarian war are coming into focus

-

America can still destroy the world

America can still destroy the worldThe Explainer The decline of U.S. military power has been greatly exaggerated