Would Americans support a military intervention in Ukraine?

The U.S. is squeamish about foreign military adventurism. But if Russia were to invade an Eastern Bloc country...?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The continuing political turmoil in Ukraine, and the geopolitical questions surrounding it, has given rise to a bit of Cold War nostalgia. And not just on Jon Stewart's Daily Show. In warning Russian President Vladimir Putin against sending troops into Ukraine, U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry reminded the Russians that "this is not Rocky IV." (That's the one with America's Italian Stallion duking it out with Soviet nemesis Ivan Drago). "Believe me," Kerry added, "we don't see it that way."

That may be true of the Obama administration — President Obama said a week ago that Ukraine isn't "some Cold War chessboard in which we're in competition with Russia" — but it's safe to say that he and Kerry aren't speaking for all Americans. On Sunday, for example, Weekly Standard editor Bill Kristol had this to say on ABC's This Week:

Look, it's nice for President Obama to say it's not a Cold War chessboard. I don't know why he says that with some disdain. That was not an ignoble thing for us, to play on that chessboard for 45 years. We ended up winning that Cold War. And I do think Putin thinks he's playing chess. He thinks he's playing even a rougher game than chess, and we have to be able to match it. [ABC News]

Kristol is a hawkish conservative commentator, not a policymaker. But some GOP lawmakers — Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.) prominent among them — have been pushing for Obama to more forcefully defend Ukraine from Russian meddling, whether it be through sterner diplomacy or moving Ukraine into NATO. A Cold War footing has gained enough traction that Sen. Rand Paul (Ky.), a leading GOP non-interventionist, waved off his colleagues, telling The Washington Post that "some on our side are so stuck in the Cold War era that they want to tweak Russia all the time, and I don't think that is a good idea."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

On the surface, it seems that Americans would probably side with the Obama administration (or Paul) over how to approach the Ukraine situation. Even strong warnings can have consequences — just think of Obama's "red line" on Syria, a rhetorical overstep that could have easily resulted in missile strikes against the country had Congress not balked after a public outcry. And as the unpopularity of Obama's limited intervention in Libya further underscores, Americans have come to dislike military meddling, especially in majority Muslim countries, over the past 12 years. "There's a new isolationism" in America, Kerry told reporters on Wednesday, and he didn't mean it as a compliment. "We are beginning to behave like a poor nation."

But could Ukraine prove the exception? Aside from the cynical observation that Ukrainians are white European Christians, the Cold War really does still hold some currency in the American imagination. Fewer events were more searing during the Cold War than the harsh Soviet crackdowns on pro-democracy movements in Eastern Europe. Watching Putin's tanks roll into Ukraine, after pro-Western demonstrators just overthrew Moscow's man in Kiev, wouldn't sit well in America.

And Russian military intervention in Ukraine isn't that far-fetched a possibility. On Wednesday, Putin started a surprise week-long military exercise in Western Russia, putting 150,000 troops, 880 tanks, 90 aircraft, and 80 navy ships into action near Ukraine's border. Russia already has military and naval bases in the Ukrainian province of Crimea, and that Black Sea peninsula is now ground zero in the Ukraine conflict.

On Wednesday, thousands of protesters gathered outside the regional parliament building in Simferopol, Crimea's capital, leading to clashes between those calling for Russian intervention and those opposed to it. Early Thursday, 50 to 60 heavily armed Russian-speaking militants seized control of the parliament and other government buildings, switching out the Ukraine flag for the Russian one.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

"They didn't look like volunteers or amateurs, they were professionals," one pro-Russia protester, Maxim, told the Associated Press. "This was clearly a well-organized operation." The militants have refused to identify themselves or make any public demands.

A suspicious mind might wonder whether these AK-47 and grenade-wielding, pro-Russian militants are trying to start a fight that could draw Russia's military into Ukraine. Ukraine's new interim government is keenly aware of that threat. Acting Interior Minister Arsen Avakov said on Wednesday that his main instruction to Ukrainian security forces nationwide is: "Don't provoke any sort of conflict or armed standoff with civilians at any cost."

NATO is rattling its collective sabers, with the member nations' defense ministers pledging Wednesday to "continue to support Ukrainian sovereignty and independence, territorial integrity, democratic development, and the principle of inviolability of frontiers, as key factors of stability and security in Central and Eastern Europe and on the continent as a whole."

But other than staging their own provocative war games, or sending in troops, NATO and the U.S. have very few options. When Russia sent troops into neighboring Georgia in August 2008 — ostensibly to protect ethnic Russians in contested South Ossetia — the Bush administration considered military attacks to stop Russia's advance, according to a 2010 book on the brief war by Ronald D. Asmus. "There was a discussion of, 'Should we consider military action to achieve our objectives?' and the view was that that was not an attractive option," Bush's national security adviser, Stephen Hadley, told Politico after the book was published. "It was a long way away, and it would be a direct military confrontation with Russia."

The West faces the same issue now. There are possibilities other than full-out war with Russia — Ukraine could end up like Cold War–era Germany, with east and west protected by Russian and NATO forces, respectively — but a hot war would always be a serious risk. "The West has very limited means of enforcing this message," Joerg Forbrig, an Eastern Europe expert with the German Marshall Fund, tells Germany's Deutsche Welle. "What we can clearly rule out is that the West would rush to the help of the Ukrainian government to safeguard this integrity."

Nonetheless, to help keep Russian troops out of Ukraine, the U.S. and its European allies may have to flirt with threatening to intervene. If that accidentally leads to U.S. military intervention, would Americans go along with it?

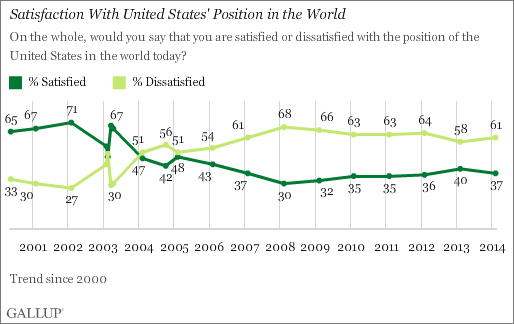

A new Gallup poll got a lot of attention for showing that, for the first time in Obama's presidency, a majority of Americans don't think their president is respected abroad. But it also shows an uptick in U.S. dissatisfaction with America's standing in the world. As this graph shows, Americans haven't been too happy with their perceived standing since the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

Another way of looking at that is Americans haven't felt like the "good guys" for more than a decade. In 2000, the U.S. was still basking in its defeat of the Evil Empire.

"The Cold War was sold to the American people as a moral confrontation, a show-down between good and evil," says Charles J. Reid Jr. at The Huffington Post. "Soviet Russia was dictatorial, expansionist, subversive, bent on global domination by fair means or foul. Several generations of Americans came of age ardently believing in this account. It echoes still in the ears of many people over the age of 40."

The main question about Ukraine intervention, then, may be: How many Americans remember the Cold War, and remember it as an American moral and geopolitical triumph? Reid concludes:

For a president to threaten force, that president must have the backing of the American people. And the dominant trope used to obtain that support, from Inchon to Baghdad, was the Cold War's "good versus evil." Millenials and immigrants, for entirely praiseworthy reasons, are no longer convinced by explanations that rely on this outdated narrative. [Huffington Post]

Hopefully, Russia will use nonmilitary tools to try to influence Ukraine's internal politics. That will make the question of support for American intervention moot.

Peter has worked as a news and culture writer and editor at The Week since the site's launch in 2008. He covers politics, world affairs, religion and cultural currents. His journalism career began as a copy editor at a financial newswire and has included editorial positions at The New York Times Magazine, Facts on File, and Oregon State University.