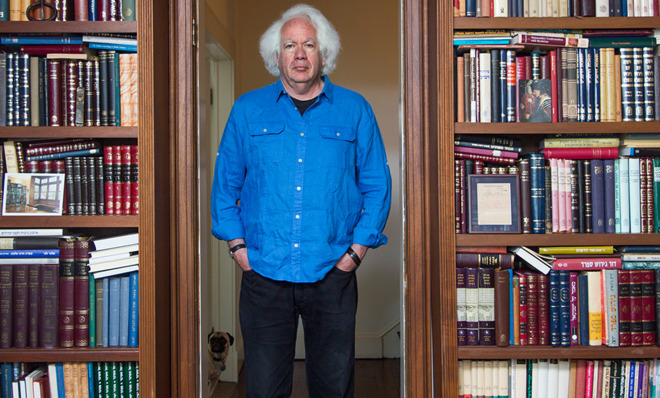

Leon Wieseltier: The last of the New York intellectuals

The New Republic's legendary former literary editor is one of the greats in the history of American letters

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

So this is how it ends — not with a bang or a whimper, but a bloodbath.

When all the gossipy stories about the death of The New Republic (where I was a contributing editor until last week) have been written, when the news of its demise has ceased to shock, and when Frank Foer and the other good and talented people who resigned rather than transform the magazine into a "vertically integrated digital media company" have landed elsewhere — then we will be faced with the grim prospect of tallying what our culture lost last week. And that is when, I hope, Leon Wieseltier, who served as the magazine's literary editor for 31 years, will receive the benediction he deserves. (A few tributes have already begun to appear, but there is room for more.)

I'm not mainly referring to Wieseltier's writing — though he penned some fabulous essays over the years. A personal favorite of mine, and one that reveals a lot about his ambitions and priorities as an editor, dates all the way back to December 1982, just before he took over the Books & the Arts pages at the "back of the book." "Matthew Arnold and the Cold War," which can't be found online, contains one of the earliest, deepest, and most enduringly insightful diagnoses of the defects and limitations of the neoconservative mind, especially when it comes to the understanding of culture.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Reviewing the inaugural issue of The New Criterion, the neocon journal founded by art critic Hilton Kramer and pianist and music critic Samuel Lipman to combat the politicization of cultural thinking and writing by the left, Wieseltier noted how the contributors to the ostensibly high-brow review frequently fell into a vulgar counter-politicization that folded cultural criticism into Cold War categories of evaluation. The result, paradoxically, was a defeat not just for incisive criticism but also for a freedom that went beyond politics — the free play of ideas. Here's Wieseltier:

The real triumph over tyranny … is not a poem about freedom, but a poem about love — a poem that neither submits nor resists, because it takes freedom for granted. Not the right politics, but no politics. The greatness of the United States in the matter of culture may be described this way — it is a place for no politics, a place for private subjects…. If the writer in the Soviet Union cannot write as he pleases because the Soviet Union is totalitarian, and the writer in the United States cannot write as he pleases because the Soviet Union is totalitarian, where on earth can he write as he pleases? [The New Republic]

Against the neocons' tendency to treat ideas as weapons in an ideological war with the left, Wieseltier championed an alternative vision found in the writings of Matthew Arnold and Lionel Trilling, Isaiah Berlin and Daniel Bell — the great liberal pluralists. For these writers, politics possesses a special importance and dignity in human life, but it is an importance and dignity quite distinct from the very different forms of beauty, grandeur, and wisdom found in literature, philosophy, music, history, painting, the natural sciences, film, theology, dance, ethics, poetry, architecture, and kindred fields of the social sciences, humanities, and arts. Each matters, each deserves critical attention, and each demands to be judged and evaluated on its own terms, without being reduced to the demands or requirements of any other domain of politics or culture.

It was this vision of productive and necessary tension among clashing regions of politics and culture that informed Wieseltier's editing — "curation" might be a more accurate way to describe it — of his precious pages at the back of the book. And that has been his great contribution to our culture.

It is also what connected his section to their closest cultural antecedents: the pages of Partisan Review during its heyday, from the mid-'40s through the mid-'60s, as the leading organ of the legendary New York intellectuals. Rejecting the efforts of the Stalinist left to judge culture and the arts by standards derived from doctrinaire Marxist-Leninism, the editors of PR combined first democratic socialist and then liberal democratic political commitments with an openness to and encouragement of modernist experimentation, even when it complicated their political projects.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

In Wieseltier's commitment to agonistic pluralism, his championing of a relentlessly combative style of thinking and criticism, and his conviction that fostering passionate thinking about high culture for an audience of educated generalists serves a high moral purpose — in all of these ways, Wieseltier may be the last of the New York intellectuals. (Yes, he's lived and worked in Washington for decades, but the boy was born and bred in Brooklyn.)

From 1983, when he took over the back of the book, through the early years of the 2000s, Wieseltier's pages were just about the only game in town for serious writing about culture. Only The New York Review of Books and the Times Literary Supplement, each with a couple dozen reviews in every issue, came close to matching the cultural heat and light that Wieseltier managed to generate with a handful of essays and reviews, and a modest budget, in nearly every issue of TNR.

Today the cultural landscape is different. Not only are old-media opinion journals (The Nation, for example) publishing much smarter and more unpredictable review essays than they used to, but there are a slew of digital outlets covering cultural topics in a variety of interesting ways — The Believer, n+1, The New Inquiry, Tablet Magazine, and many others — as well as old-time (Boston Review) and new-fangled (LA Review of Books) cultural journals whose content can be easily and instantly accessed online.

The question, as always, is whether the increased quantity will match (let alone surpass) the quality Wieseltier managed to achieve in issue after issue of TNR.

I tend to doubt it. Editing is a talent, true talents are rare, and Wieseltier was one of the greatest editors in the history of American letters. His greatness covered the full gamut of the editorial process. He had a keen eye for spotting young writers with potential — Jed Perl, James Wood, Adam Kirsch, among many others — and a willingness to give them assignments, space, and encouragement that allowed them to reach and grow. He was extremely good at finding established academics and other experts with the writing chops to speak to a broader audience — and to match them up with topics that produced clarifying insights and conflicts. And he was a master of crafting stiletto-sharp argumentative prose in a collaborative process with his writers.

I discerned my own vocation as a critic while reading his pages — I was a subscriber for 23 years, up until last week, and always began reading the magazine at the back — and I honed my skills as a writer trying to emulate the style of muscular elegance he and his best writers favored. When I appeared in his pages for the first time — in 2006 — it felt like vindication. I had finally arrived as an intellectual.

Who will the next generation of aspiring intellectuals look to for inspiration and models to emulate? I have no idea. But I do know they will have a harder time of it in a world without The New Republic.

An essay of appreciation like this cannot help but read like an obituary. That's unfair. Wieseltier is only 62 years old. With any luck, he'll be around, contributing in vital ways to our culture, for a long time to come.

But an era is nonetheless over. In one of the crude Silicon Valley clichés he spouted in the weeks leading up to the implosion at the magazine last Thursday and Friday, TNR's new chief executive Guy Vidra said he wanted to "break shit." Well, he has succeeded.

And in doing so he (along with owner and publisher Chris Hughes) has made an enemy of all who care about the fate of ideas in America. (I can't speak for my fellow contributing editors to the magazine, but that's certainly why I've chosen to resign the honorific title.)

As we mourn the loss of something precious and perhaps irreplaceable from our culture, let us take a moment to say a word of thanks to Leon Wieseltier for his 31 years of tireless service to the life of the American mind.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown