Is it now OK to have sex with animals?

A baffling new article in New York suggests that many people think the answer is yes...

I have a very 2014 question for you: How would you respond if you found out that a man living down the street regularly has sexual intercourse with a horse?

Would you be morally disgusted? Consider him and his behavior an abomination? Turn him in to the police? (This would be an option in the roughly three-quarters of states that — for now — treat bestiality as a felony or misdemeanor.)

Or would you perhaps suppress your gag reflex and try hard to be tolerant, liberal, affirming, supportive? Maybe you'd even utter the slogan that deserves to be emblazoned over our age as its all-purpose motto and mantra: Who am I to judge?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Thanks to New York magazine, which recently ran a completely nonjudgmental 6,200-word interview with a "zoophile" who regularly enjoys sex with a mare — unironic headline: "What it's like to date a horse" — these questions have been much on my mind.

They should be on yours, too.

Because this is a very big deal, in cultural and moral terms.

No, not the fact of bestiality, which (like incest) has always been with us, but the fact of an acclaimed, mainstream publication treating it as a matter of complete moral indifference. (Aside, of course, from the requisite concern about animal abuse — a nonhuman analog to the pervasive emphasis on consent as the only relevant moral criterion for judging sexual behavior. The interview dispenses with this worry by informing us that the zoophile regularly brings his equine lover to orgasm orally — and that she often initiates acts of intimacy, showing that she appears to enjoy their sexual interactions.)

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Am I worried that large numbers of people will soon choose to shack up with their pets or farm animals? Not at all. I can't imagine that very many people will ever be drawn to bestiality, no matter how casually it is treated in the media.

Why, then, is the New York interview a big deal? Because it's perhaps the most vivid sign yet that, in effect, the United States (and indeed the entire Western world) is running an experiment — one with very few, if any, antecedents in human history. The experiment will test what happens when a culture systematically purges all publicly affirmed notions of human flourishing, virtue and vice, elevation and degradation.

Moral and religious traditionalists have seen this coming and warned about its consequences for years. And indeed, they are the ones raising the loudest ruckus about the New York interview.

I share some of their concerns. But there are at least two problems with their analysis of the experiment.

First, the trads are wrong to blame the purging of publicly affirmed notions of human flourishing on the spread of relativism. Viewed from inside traditionalist notions of virtue and vice, a culture that seeks to redefine "normal" to include zoophilia might seem like a culture defined by relativism. But it isn't. Rather, it's a culture fervently devoted to the moral principle of equal recognition and affirmation — in a word, to an absolute ethic of niceness. Moral condemnation can be mean, and therefore it's morally wrong — that's the way growing numbers of Americans think about these issues.

Of course, these nonjudgmental Americans would think differently — they would continue to publicly affirm notions of human flourishing and condemn acts that diverge from the norm — if they confidently believed in the foundation of these judgments. But increasingly, they do not. Judeo-Christian piety used to supply it for many, but no longer.

Then there's the option of basing our judgments on what conservative bioethicist Leon Kass once called "the wisdom of repugnance" — that is, on our commonsense moral intuitions. But as the liberal philosopher Martha Nussbaum has argued, the "ick factor" just isn't a reliable basis on which to make moral evaluations. And we know that from lived experience. Interracial romances once seemed icky, but then they didn't. Next it was homosexual acts that passed through the looking glass from repellant to respectable. Faced with this slippage and uncertainty — with a long string of reversals in moral judgment — it's no wonder that the ethic of unconditional niceness increasingly trumps all other considerations.

And that brings us to the second way in which the trads go wrong — in speaking confidently about how we're "galloping toward Gomorrah." This implies that they know exactly where the experiment is going to end up. The truth is that they — and we — have no idea at all. Because there has never been a human society built exclusively on a morality of rights (individual consent) and an ethic of niceness, with no overarching vision of a higher human good to override or compete with it.

As I noted above, I find it hard to imagine that more than a tiny fraction of human beings will ever choose to engage in sex acts with animals, even if and when the taboo has been thoroughly deconstructed and the behavior mainstreamed by dozens of sympathetic stories in the media. I suspect the same is true about incest and polyamory. Most people will continue to live boring, mundane sex lives, monogamously committed to one human being of the opposite sex at a time.

So what, then, is there to worry about? Why is this cultural experiment a big deal?

Because it stands as a stunning testament to our ignorance about ourselves. Roughly 2,500 years since Socrates first raised the question of how we should live, several centuries since the Enlightenment encouraged us to seek and promulgate scientific knowledge about the universe and human nature, Western humanity seems to have come to the conclusion that we haven't got a clue about an answer. There is no consensus whatsoever about what ways of life are intrinsically good or bad for human beings.

Get married and have kids? If that's what you want, sounds good. Live in a polyamorous arrangement? As long as everyone consents, have fun. What about my intense desire to copulate with a horse? Just make sure no one gets hurt — with hurt defined in the narrowest of terms (covering physical harm and the violation of personal preferences).

That's all we've got. Or at least all we're left with, now that we've shed the (ostensibly) discredited notions of human virtue that most people once affirmed.

Is that good enough? Can we do without a publicly affirmed vision of human flourishing? Fulfilling personal preferences (whatever they happen to be), seeking consent in all interactions, and abiding by the imperative of universal niceness — is that sufficient to bring happiness? Or will a world that tells us in a million ways that we are radically undetermined in our ends leave us feeling empty, lost, alone, unmoored, at sea, spiritually adrift?

I have no idea.

But I suspect we're going to find out soon enough.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

Ultimate pasta alla Norma

Ultimate pasta alla NormaThe Week Recommends White miso and eggplant enrich the flavour of this classic pasta dish

-

Death in Minneapolis: a shooting dividing the US

Death in Minneapolis: a shooting dividing the USIn the Spotlight Federal response to Renee Good’s shooting suggest priority is ‘vilifying Trump’s perceived enemies rather than informing the public’

-

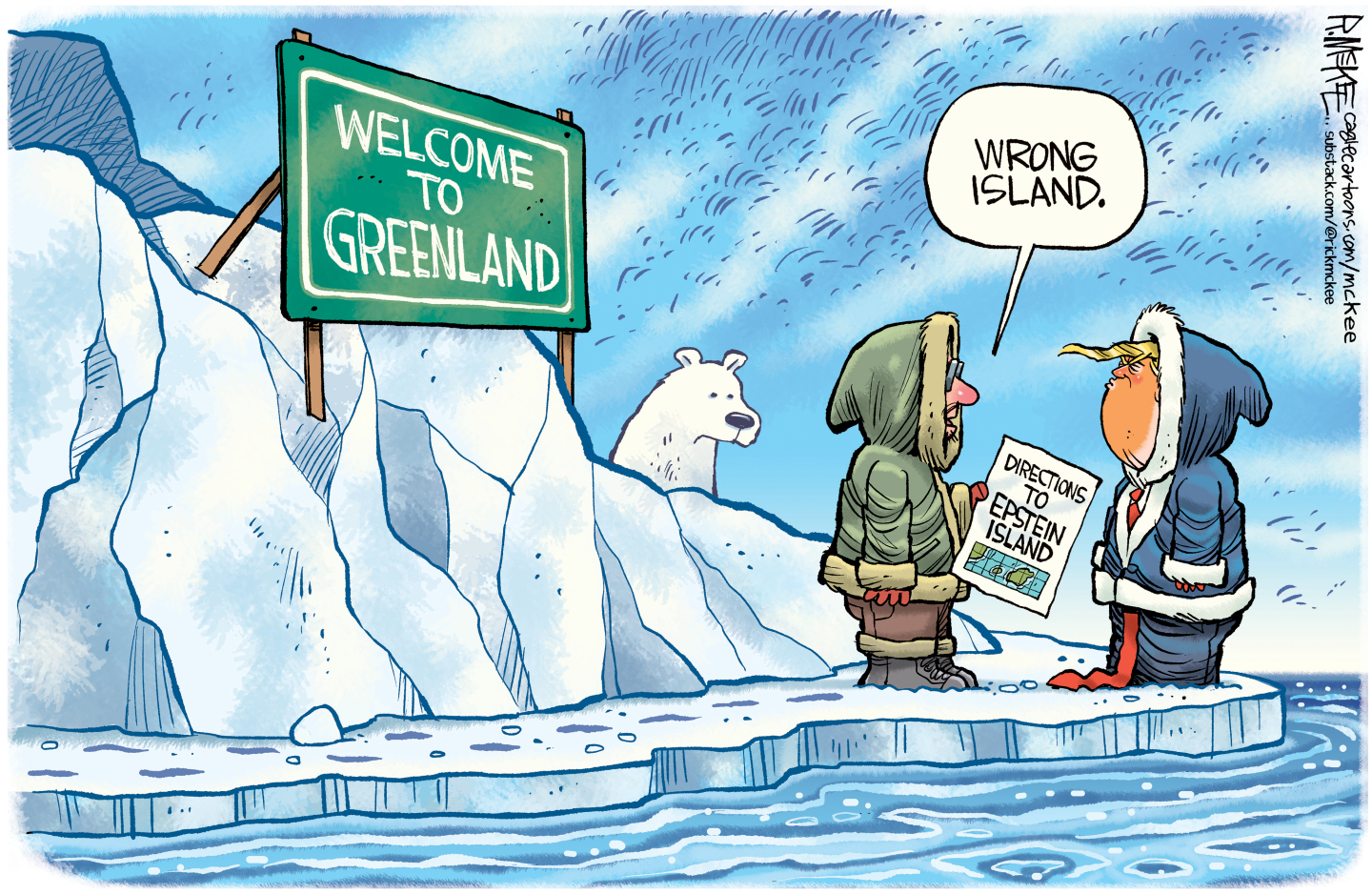

5 hilariously chilling cartoons about Trump’s plan to invade Greenland

5 hilariously chilling cartoons about Trump’s plan to invade GreenlandCartoons Artists take on misdirection, the need for Greenland, and more