Do you want to increase crime, poverty, and addiction in your area? Build a casino.

Casinos are often billed as economic cure-alls for ailing regions. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Almost every economically depressed region in America is begging for a casino salvation. Casinos have opened in nearly ever major city in Ohio. Baltimore residents are celebrating new gambling jobs at the Horseshoe. Crime-ridden Springfield, Massachusetts, is approved for an MGM-led casino. Just across the border, four casinos are planned for the depressed areas of upstate New York.

These poor underemployed regions are being sold a scam. This racket portrays itself as a great deal: Local people get a load of new jobs, the state collects more tax revenue, and the area will boom as it brings in wealthy tourists from beyond the region. There are dreams of high-class gamblers coming in from around the globe, their C-notes trickling to the hotel staff and the dealers, all the way down to struggling local attractions and the new, locally owned coffee shops that will hopefully spring up in the casino's shadow.

Maybe Bobby Flay or David Chang or some other famous chef will come. And eventually, if all goes right, country music stars and stand-up comedians will be lining up to perform at an entertainment venue and upscale mall. This is part of Phase Two, scheduled to kick off in 2024.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What really happens is this: Jobs are created, temporarily. Then the casinos and the statehouses prey upon the elderly and the poor. The table games, which justified hiring locals, are gradually replaced by slots, and maybe a sports bookie behind barred windows. Shambolic pensioners and working-class gambling addicts spend their days sitting at slot machines that are designed by geniuses who study the art and brain science of addiction. Complimentary bus rides are offered to transport more of the indebted and dependent to the cash gobbler.

The only noticeable pickups in business happen when welfare deposits are made. State-issued welfare debit cards are often usable at casinos and strip clubs, which is why the gambling trade calls the announcement of every new casino a "rake" on welfare payments. The casinos are a way of clawing back welfare revenue and a hidden way of making the state's financing more regressive. It's another lottery system, but with more middlemen.

Money doesn't trickle down to local residents. It flows out from them in armored trucks to global gaming conglomerates, executives in Vegas, and to the state treasury. In the rarest of rare cases, a few members of an obscure Indian tribe will collect absurd $100,000 annual stipends. But even the inventive Pequot tribe can't bus in enough Chinese immigrants to sustain that kind of return on Sic Bo and Pai Gow. So the stipend comes to an end, too.

People should have figured this out by now. How many six-figure high rollers are planning long, indulgent trips to Ledyard, Connecticut, or Tunica, Mississippi? Maybe they're interested in tuberculosis for their holiday? Instead of upscale restaurants and coffee shops, new casinos in down-and-out areas are followed by check-chashing operations and the kind of Taco Bell that people call "wild."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Prostitutes come, too. Local grocers start to move out as the crime rate increases. The real Phase Two is when the area becomes so broke, so sketchy, and so unattractive to anyone with money that the credit dries up and the casino closes.

The closure of four major casinos in Atlantic City this year should be a warning to everyone in Maryland, the Midwest, New York, and New England who wants in on this game. The success of Atlantic City in the 1920s was predicated on a legal and tourism situation that will never arise again. It was a place where gambling, drinking, prostitution, and sandy beaches could be easily found, right near New York City.

But once the city's Prohibition premium went away, and flights to Miami Beach (and later Las Vegas) became cheap enough, the town was doomed. The nice restaurants and steakhouses at the Borgata are sustained by one-evening stop-ins of people renting beach houses at the considerably more tidy towns of Avalon, Cape May, and Sea Isle City.

Gambling towns that attract rich clients are sustained, in part, by the availability of some other vice that is banned or unavailable elsewhere. Although prostitution is prohibited in the city, Las Vegas exists near a zone where prostitution is legal. Macau also has legal prostitution and takes a libertine attitude toward narcotics, too. Despite Islamic prohibitions on gambling, drink, and child rape, Moroccan cities like Marrakech and Tangier find ways to provide them to Western decadents who go there "for the boys and the hashish," as William S. Burroughs did.

If you want to increase poverty, increase the regressive nature of state government financing, increase crime and prostitution, increase gambling addiction and depression, and increase obesity, then go ahead and lobby your state government for a new casino. But if you want to compete for the high-end gambling dollar, that will require more illegal drugs and sex slavery than you can find in the Catskill Mountains or Springfield, Massachusetts.

Michael Brendan Dougherty is senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is the founder and editor of The Slurve, a newsletter about baseball. His work has appeared in The New York Times Magazine, ESPN Magazine, Slate and The American Conservative.

-

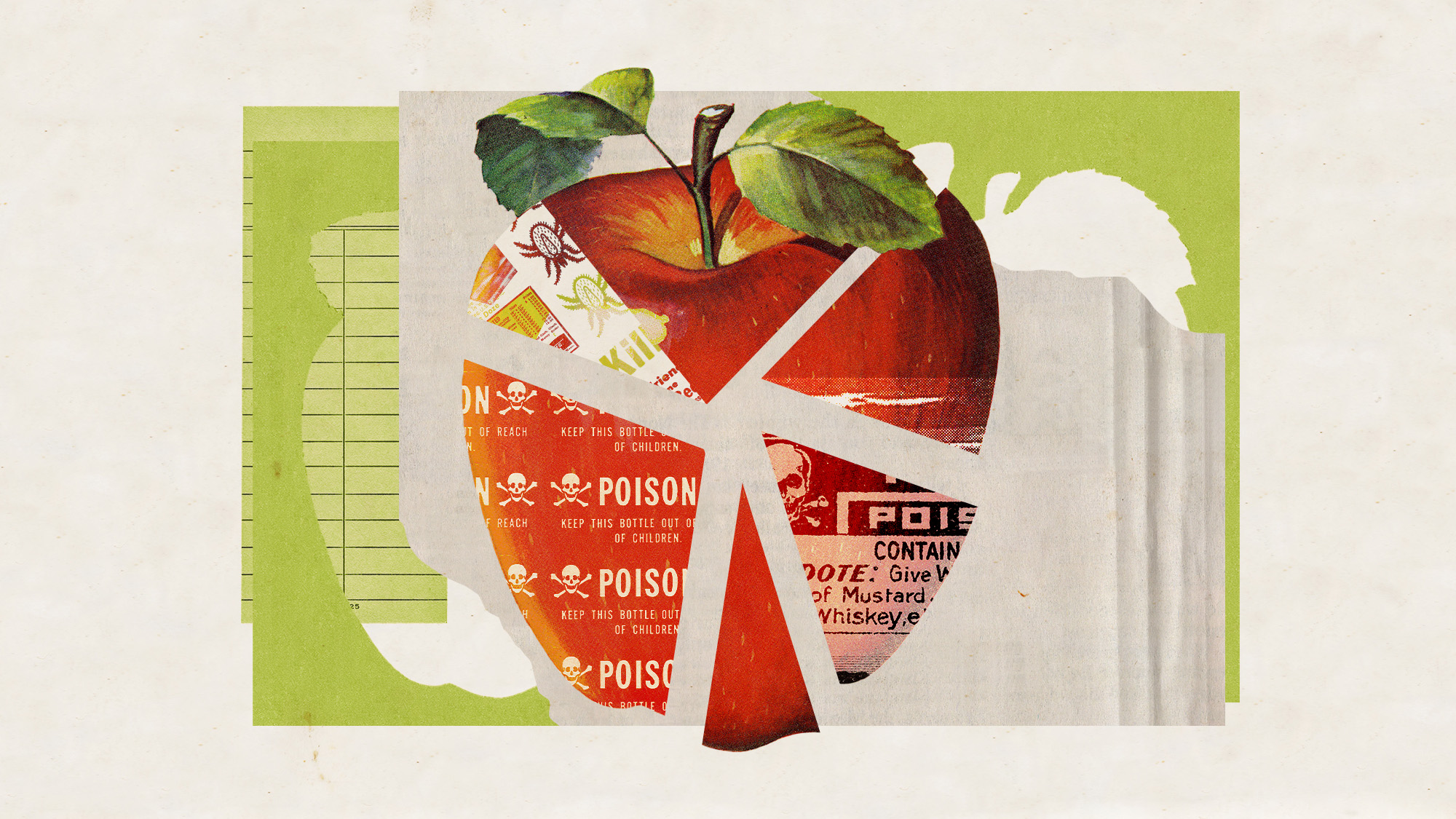

Europe’s apples are peppered with toxic pesticides

Europe’s apples are peppered with toxic pesticidesUnder the Radar Campaign groups say existing EU regulations don’t account for risk of ‘cocktail effect’

-

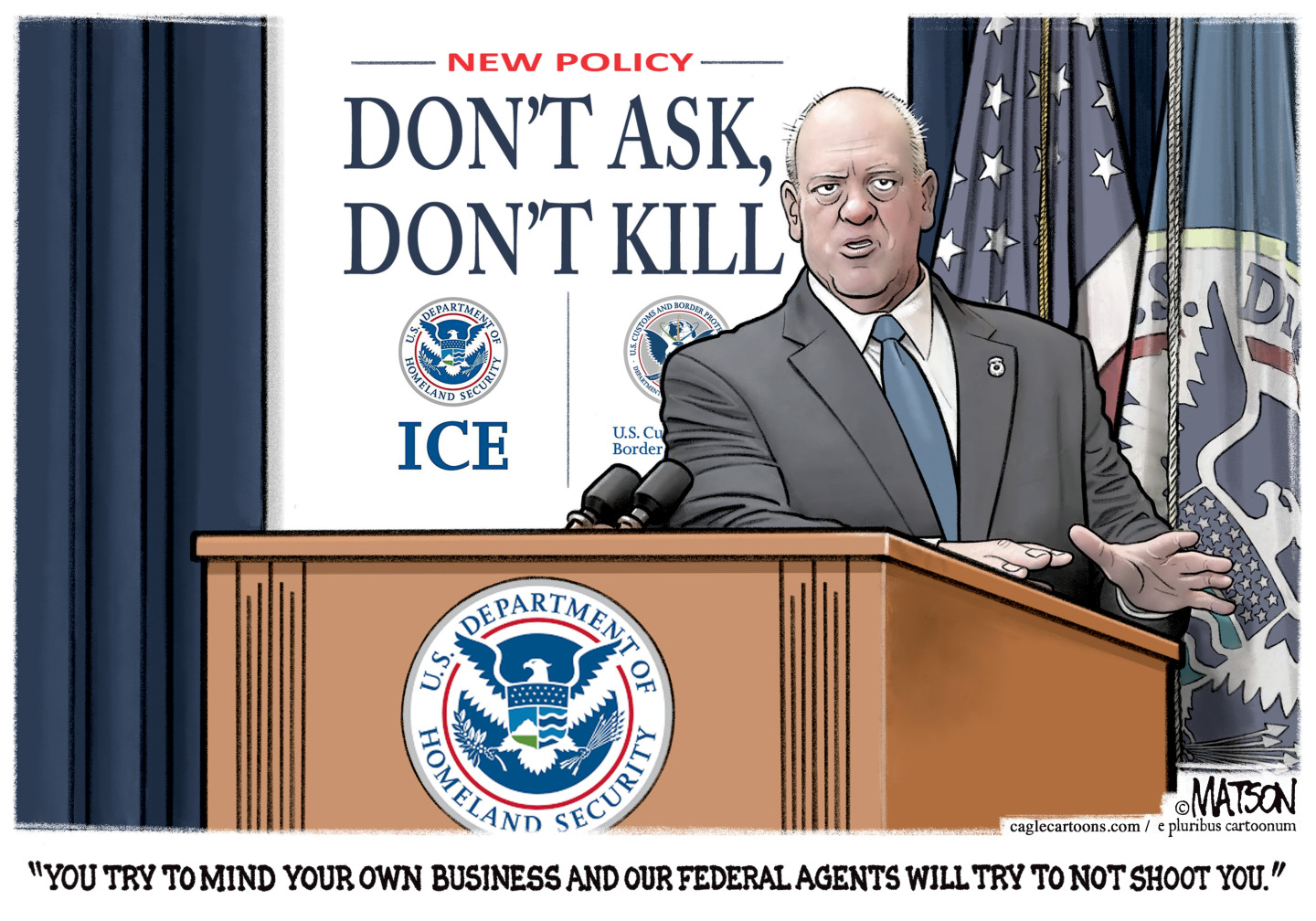

Political cartoons for February 1

Political cartoons for February 1Cartoons Sunday's political cartoons include Tom Homan's offer, the Fox News filter, and more

-

Will SpaceX, OpenAI and Anthropic make 2026 the year of mega tech listings?

Will SpaceX, OpenAI and Anthropic make 2026 the year of mega tech listings?In Depth SpaceX float may come as soon as this year, and would be the largest IPO in history