The end of the New Deal?

The GOP's economic program is an effort to destroy the architecture of social justice and corporate responsibility in America

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

America was rescued from the Great Depression by the New Deal — and then pushed back into recession when Franklin Roosevelt briefly and prematurely moved toward a balanced budget. Three-quarters of a century later, a second depression was averted by an act of government that did more and spent more to counter a collapse in consumer demand and the credit markets. It briefly seemed that we as a nation had learned the imperative that FDR expressed on Inauguration Day in 1933 — the necessity for "action, and action now."

But FDR had come to office more than three years into a catastrophic downturn. Americans rallied to the hope he brought, but didn't expect an instant turnaround.

Barack Obama entered his presidency only months into the financial crisis. Compounded by the pressures of a hyper-media age, the public mood didn’t accord him many months before punishing him and his party in the midterm elections for a recovery that was taking hold but not fast enough, a recovery still more a statistical artifact than a fact of people's lives. There are now more convincing signs of economic revival, which could yield decisive and Democratic dividends in 2012 — if the results of the 2010 elections don’t stall a reverse in growth and job creation.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The counter-arguments Obama makes will determine not only America's decision in the next election, but America’s direction for the next generation.

That's one of the two great dangers now — for the nation and the president. The other danger, moving like an ideological freight train through the House of Representatives and across state governments and the judiciary, is the erosion or repeal of the New Deal itself. This is the aim of a Republican party now far to the right of Dwight Eisenhower and Richard Nixon — and even the surprisingly pragmatic Ronald Reagan.

The GOP offered Americans a scapegoat in the recent campaign: A government doing big things in the face of a grave challenge was turned into the Big Bad Government. The very government that was preventing catastrophe was portrayed as causing it. It was an appeal to a forgotten Hooverism — to the discredited but widely received notion that cutting spending is the straightest path back to prosperity. Voters wouldn’t have bought that message if economic progress had been clearer and swifter; in 1984, they hardly cared about Walter Mondale's calls to reduce the deficit when it was morning in Ronald Reagan’s America. And the majority of voters who shifted toward Republicans last November didn't necessarily embrace their argument, but apparently concluded that there was nothing wrong with giving them their chance; in a divided government, the parties might be forced to work together.

The wintry weeks of December did see a brief season of bipartisan compromise. But now the GOP, in the House and in newly captured state capitals, is marching relentlessly to the far right. That course won’t advance the economy. But concern for jobs is the pretext and not the purpose of a Republican program that reflects an instinct which long lay mostly dormant in the recesses of conservative aspiration — to roll back the consensus that has prevailed since the 1930s and to remake the future in the image of a laissez-faire past.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

In the House of Representatives, where John Boehner is less speaker than servitor of the Tea Party, the GOP has passed a budget resolution that begins the rollback. It slashes education; unemploys teachers, police, and potentially millions of others; and shreds the fabric of the safety social net, taking the most from those who have the least. The measure attempts to undo basic environmental, consumer, and financial regulation by defunding the regulators. Next on the chopping block, if Republican House budget guru Paul Ryan has his way, will be Medicare and Social Security, the heart of the New Deal legacy.

As economics, the reactionary spasm makes no sense. The evidence is already there. After two years of Obamanomics, forecasts for U.S. growth are being revised upward. At the same time, in the wake of sudden and sharp retrenchment in Britain, what's rising is unemployment; growth is falling and house prices are predicted to plummet again. But as ideology, the Republican policy makes perfect sense — and presents a perfect opportunity for the true believers who were vanquished during the New Deal and decades afterwards. They lied about health reform — from nonexistent "death panels" to nonexistent cuts in Medicare benefits for the elderly. The Republicans opposed the bill and now propose to defund it. But what the House just passed goes far beyond that: It's a draconian down payment on dismembering the architecture of social justice and corporate responsibility in America.

That's why the GOP doesn’t care if the numbers actually add up. That’s why Boehner, asked about the jobs that would be lost because of his party’s program, could blithely reply: "So be it." (There’s also the obvious calculation that the Republicans' budget proposal, if enacted, could damage the economy enough to pave their road to the White House in 2012.)

On another front, Republican governors have opened their own assault on the New Deal. In Wisconsin, the budget would have been in balance except for hastily enacted special interest giveaways and tax cuts. Citing the deficit he had just created, newly elected Gov. Scott Walker launched a furious drive to smash unions — to deprive public employees of collective bargaining rights, which had nothing to do with fiscal pressures, since the unions have already agreed to givebacks on pension and health care benefits to help close the budget gap in future years. Similar efforts are underway in Ohio and Indiana.

States are in trouble and do have to make cuts or, as Jerry Brown has dared to suggest in California, raise some taxes. But going after the very existence of unions, by today one of the less robust legacies of the New Deal, is no answer to fiscal problems nor was it any apparent part of the new governors' campaigns across the Midwest. Once in power, they have seized the chance to wreak their ideological will.

On a third front — on the federal bench — Republican judges, in the dark spirit of Bush v. Gore, have taken to declaring health reform unconstitutional. And here, too, the cause they have in mind is bigger than the case before them. If upheld, their rulings could threaten the entire regime of national regulation, and a generation of civil-rights legislation, by returning to the narrow, pre-New Deal reading of the federal power over interstate commerce — a reading under which an earlier Supreme Court struck down a law prohibiting child labor.

Republican strategy has been played out as a shell game, in which crocodile tears about jobs have been traded for jeremiads about deficits — and not incidentally, a tea-fueled attack on women's rights, Planned Parenthood, scientific research, and equality for gays and lesbians.

Just weeks ago, in the State of the Union message, the president bent the narrative in a different direction — toward the kind of optimistic message that usually carries the day in American politics. But it’s not enough simply to repeat the mantra "to win the future;" it’s essential to vivify the summons, to show people in concrete terms what can be gained — and now, because of the Republican budget, what could be lost.

Instead the dialogue is drifting back toward GOP ground. Without making an explicit case for phasing in deficit reduction, the Obama budget, too, proclaims cuts, just fewer of them — for example, a 50 percent cut in home-heating assistance for families that can't otherwise afford to stay warm in the winter. This is unconscionable on the merits and unconvincing politically. If the question is "who’s tougher on the deficit?" the answer isn’t Obama and the Democrats; the Republicans who dug us deep into deficits with the Bush tax cut and a concocted war will now go to any length and cut any program, unless it cossets the comfortable. The GOP is not only willing, but enthusiastic about waging and winning this bidding war.

So the president has to cast the choice in larger terms, and his message has to break through. The Senate can and will refuse to pass the House’s budget measure; Obama has and would use his veto pen. Then the process may break down — and within a matter of days, when the federal government’s current spending authority runs out. Democrats may assume that Republicans will be blamed for a government shutdown as they were in 1995. But Bill Clinton and his party went into that showdown backed by a powerful narrative: The GOP was insisting on $250 billion in top-end tax cuts financed by $270 billion in Medicare cuts. If a showdown comes again, this president will command the nation's attention and the case he makes will probably determine not only America's decision in the next election, but America’s direction for the next generation.

One possibility — still — is a new progressive era, ratified in 2012 as the economy rises. The other is a regressive era of retreat from economic and social justice, with the subversion or undoing of decades of achievement from Medicare and civil rights to financial and health reform, all the latter day progeny of the transformation of this country in the 1930s. And as they are already proving, the GOP reactionaries yearn for even more — to upend most of the New Deal itself.

The Republicans may again make the mistake of overplaying their hand. But the stakes couldn’t be higher — and more than ever, the president faces "the fierce urgency of now."

-

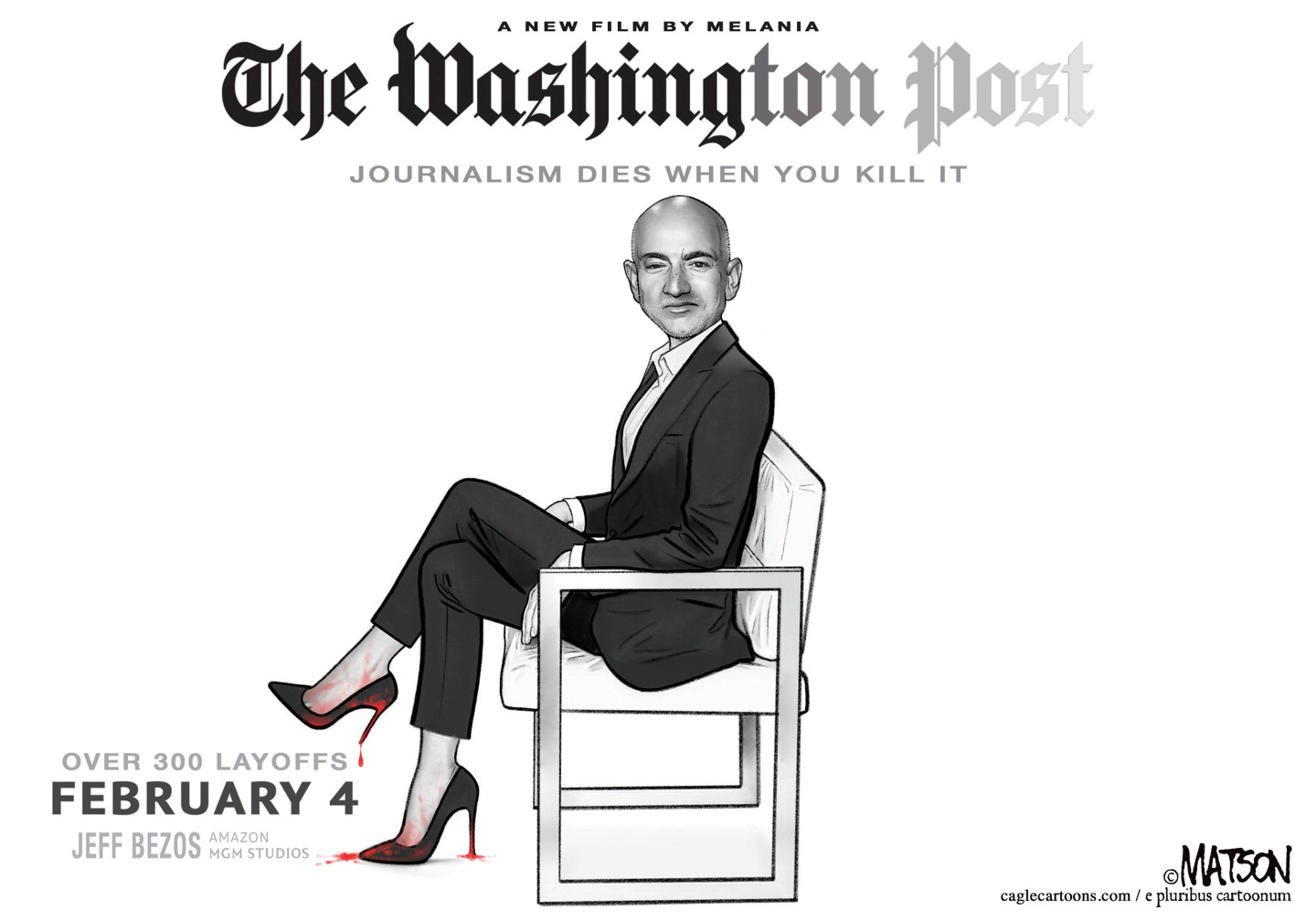

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'Cartoons Artists take on a girlboss, a fetching newspaper, and more

-

The fall of the generals: China’s military purge

The fall of the generals: China’s military purgeIn the Spotlight Xi Jinping’s extraordinary removal of senior general proves that no-one is safe from anti-corruption drive that has investigated millions

-

Why the Gorton and Denton by-election is a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’

Why the Gorton and Denton by-election is a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’Talking Point Reform and the Greens have the Labour seat in their sights, but the constituency’s complex demographics make messaging tricky

-

The FCC needs to open up about LightSquared

The FCC needs to open up about LightSquaredfeature A politically-connected company that wants to build a massive 4G internet network seems to have benefited from some curious favors from the feds

-

Do you believe in magic?

Do you believe in magic?feature The House speaker's debt-ceiling proposal is smoke and mirrors. That's what's good about it

-

Will both sides blink on the debt ceiling?

Will both sides blink on the debt ceiling?feature With the financial credibility of our nation at stake, and both parties facing massive political risks, lawmakers might agree to a grand bargain after all

-

Dine and dash?

Dine and dash?feature Politicians are jockeying for advantage as the bill comes due on our gaping national debt. But without an agreement soon, we'll all be stuck with the check

-

The GOP's dueling delusional campaign ads

The GOP's dueling delusional campaign adsfeature Slick ads attacking Jon Huntsman and Tim Pawlenty as reasonable moderates show just how divorced from reality today's Republican Party is

-

Bibi turns on the charm

Bibi turns on the charmfeature In the fight over Israel's borders, Netanyahu takes the upper hand

-

Get rich slow

Get rich slowfeature A cheap U.S. dollar is no fun, but it will get the job done

-

Bin Laden, the fringe Left, and the torturous Right

Bin Laden, the fringe Left, and the torturous Rightfeature The killing of the architect of September 11 has provoked predictable remonstrance from the usual suspects