China has an ISIS problem

Uighur militants have been spotted in Syria. The last thing China wants is for them to return home.

Seven Chinese nationals were recently detained in Turkey as they attempted to enter Syria. The Chinese, described as hailing from the traditionally Muslim province of Xinjiang, were detained by border guards.

The incident has highlighted China's growing problem with its own Muslim minority. Chinese officials are worried radicalized Uighurs traveling abroad to train and fight will return with skills that could bolster China's domestic insurgency.

This is a small problem that will become a much bigger problem in the near future.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Xinjiang Autonomous Region is China's westernmost territory. Twice as large as Texas, it was incorporated into China in the 18th century. The Uighur people, the traditional dominant ethnic group, are Central Asians of Turkic origin and predominantly Muslim.

They are also unhappy. Since 1955, the Chinese government has ran a settlement program for other Chinese — particularly Han Chinese — to migrate to Xinjiang. Native Uighurs feel their homeland is being colonized by outsiders, their culture is now the minority and there are fewer economic opportunities for them as there are for recent arrivals. Uighurs have also felt pressure on their Muslim faith.

The result has been a growing Uighur insurgency that has allegedly carried out terrorist attacks not only in Xinjiang but the rest of China. The Chinese government blames Uighur terrorists not only for attacks against Han Chinese and government facilities within Xinjiang and also an attack in Beijing's Tiananmen Square in October 2013 and a mass knife attack at Kunming train station that killed 29 and left 140 injured. China claims the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM) is responsible, a radical group that advocates an independent East Turkestan incorporating part of Xinjiang.

Chinese Uighurs have been going abroad to train and fight. Aspiring jihadis travel overland to Vietnam or Thailand, then on to the Middle East. More than 800 have been stopped in Vietnam in one year alone. China has even set up a special police unit nicknamed “4.29” to stop human traffickers in southern border states neighboring Southeast Asia.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Chinese Jihadists were first reported in Syria in 2012, and in September of last year one was captured by the Iraqi military. China's state-run tabloid Global Times reported in December that 300 Chinese nationals were fighting in Iraq and Syria. In 2014, Islamic State leader Abu Bakr Al-Baghdadi criticized Chinese rule in Xinjiang and asked Beijing's Muslims to pledge allegiance to him instead.

Chinese jihadists aren't just traveling to the Middle East. Last year an Israeli foreign policy analyst warned a Chinese delegation to Israel that 1,000 jihadis were training at a Pakistani military base. Chinese have also been detained in Indonesia seeking out extremist Islamic groups.

The insurgency in Xinjiang, bolstered with ex-former fighters, would make the Chinese government's job of pacifying the region much harder. The prospect of having to face returned fighters with military experience and training in laying improvised explosive device and suicide attacks is deeply concerning to Beijing.

The jihadist movement represents a major challenge to China's Communist Party rule. Terrorist attacks strike at one of the Party's core mandates, the preservation of order. It also cuts against the Party's survival instincts: the government worries such attacks would show that rebellion against the government is possible, even violent rebellion, and encourage other groups with grievances to push back against Party rule.

In addition to attacks inside Xinjiang and throughout the rest of China, jihadists are well positioned to conduct attacks against China's energy infrastructure. Much of China's natural gas — which the government plans to more than double in an attempt to combat pollution — passes through Xinjiang on its way from Central Asia. Attacks on natural gas pipelines and facilities could have a negative impact on China's economic growth.

China's response to this problem has been ham-handed. A recent call by Chinese leader Xi Jinping to increase economic opportunity for Uighurs is probably too little, too late. The government instituted bans on beards and veils on city buses in Xinjiang, a move that could only further alienate the general population. China's state media has stepped up reports that Uighurs traveling to the Islamic State have been used as cannon fodder, or executed for desertion.

The Chinese government is completely opposed to all of the insurgents' demands and even if it wasn't, negotiations with jihadists seldom go well. China's crackdown on Uighurs is only adding fuel to the revolt, and the increasing number of extremist movements worldwide means greater opportunity to fall in with radicals. China's ISIS problem is not going away any time soon.

Kyle Mizokami is a freelance writer whose work has appeared in The Daily Beast, TheAtlantic.com, The Diplomat, and The National Interest. He lives in San Francisco.

-

Nepal chooses toddler as its new ‘living goddess’

Nepal chooses toddler as its new ‘living goddess’Under the Radar Girls between two and four are typically chosen to live inside the temple as the Kumari – until puberty strikes

-

October 5 editorial cartoons

October 5 editorial cartoonsCartoons Sunday's political cartoons include half-truth hucksters, Capitol lockdown, and more

-

Jaguar Land Rover’s cyber bailout

Jaguar Land Rover’s cyber bailoutTalking Point Should the government do more to protect business from the ‘cyber shockwave’?

-

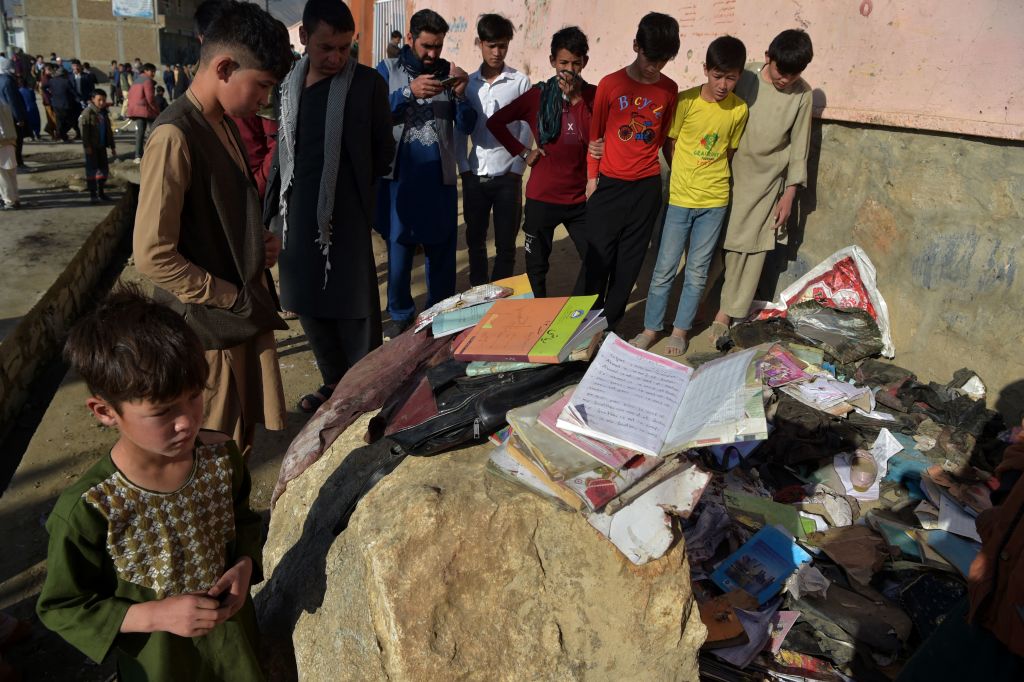

Bombing at girls' school in Kabul kills at least 50, including students

Bombing at girls' school in Kabul kills at least 50, including studentsSpeed Read

-

Garland says DOJ is 'pouring its resources' into stopping domestic terrorists 'before they can attack'

Garland says DOJ is 'pouring its resources' into stopping domestic terrorists 'before they can attack'Speed Read

-

Suspected Israeli cyberattack on Iranian nuclear site complicates U.S.-Iran nuclear deal talks

Suspected Israeli cyberattack on Iranian nuclear site complicates U.S.-Iran nuclear deal talksSpeed Read

-

North Korea fires 2 ballistic missiles into sea

North Korea fires 2 ballistic missiles into seaSpeed Read

-

U.S. airstrikes target Iranian-backed militia facilities in Syria

U.S. airstrikes target Iranian-backed militia facilities in SyriaSpeed Read

-

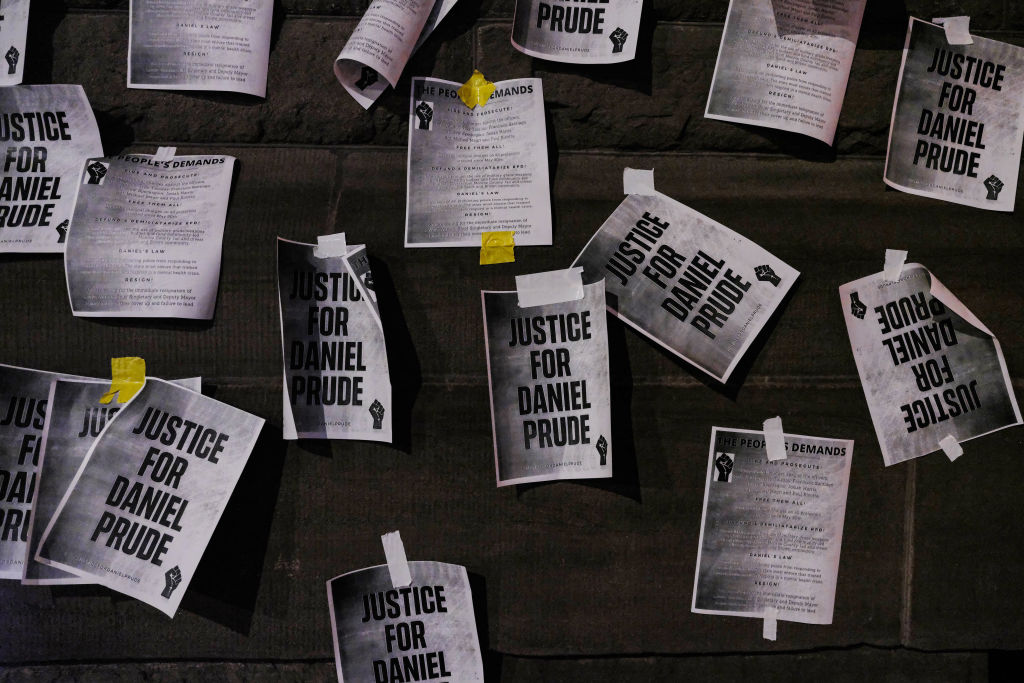

Rochester police who killed Daniel Prude during mental health crisis won't face charges

Rochester police who killed Daniel Prude during mental health crisis won't face chargesSpeed Read

-

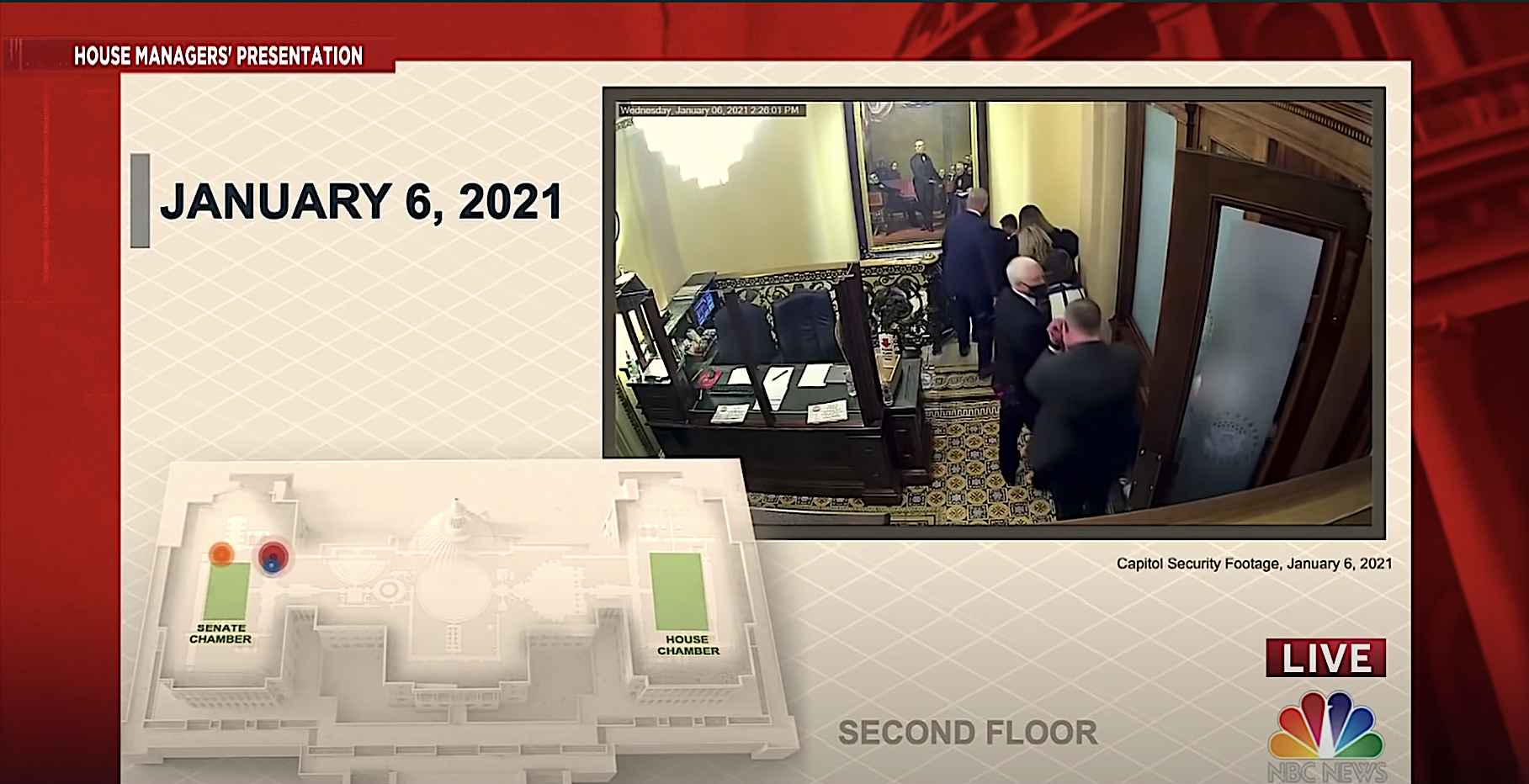

Mike Pence's 'nuclear football' was also apparently at risk during the Capitol siege

Mike Pence's 'nuclear football' was also apparently at risk during the Capitol siegeSpeed Read

-

Trump publicly attacked Pence during the Capitol riot knowing Pence was in trouble, GOP senator suggests

Trump publicly attacked Pence during the Capitol riot knowing Pence was in trouble, GOP senator suggestsSpeed Read