Nepal chooses toddler as its new ‘living goddess’

Girls between two and four are chosen to live inside the temple as the Kumari – until puberty strikes

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

“She was just my daughter yesterday, but today she is a goddess.” So said the father of Aryatara Shakya, the two-year-old proclaimed Nepal’s new “living goddess”. Carried by family members from their home to a temple palace in Kathmandu, the toddler was installed as the latest Kumari last week during the country’s most significant Hindu festival, Dashain.

“My wife during pregnancy dreamed that she was a goddess,” Ananta Shakya told The Associated Press, “and we knew she was going to be someone very special.”

The secret life of a Kumari

In a tradition stretching back 300 years, the Kumari is revered by both Hindus and Buddhists in Nepal and parts of India as an embodiment of the divine female energy. Chosen from the Shakya clan, Newari Buddhists indigenous to the Kathmandu valley, the girls are typically aged between two and four, and must meet strict physical criteria: “unblemished skin, hair, eyes and teeth”, said AP. During festivals, the Kumari is “wheeled around on a chariot pulled by devotees”, dressed in red and with a “third eye” painted on her forehead.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

“But no one really knows what happens on the induction day,” said the ABC – “not even the Kumari herself, being too young to remember.” The girls spend most of their childhood sequestered within the temple, although traditions have evolved to include some private tutoring. They are rarely allowed outside – beyond the temple walls, their feet are not allowed to touch the ground.

Former Kumari Preeti Shakya held the position for eight years, before “returning to an anonymous suburban life” at the age of 11. During her time inside the Kumari Ghar, her family “visited just once a week”; her only friends were the family of the official Kumari caretakers. “I remember watching TV and seeing modern dresses and I really wanted to wear them,” she told the news site.

During her reign, Preeti blessed the King of Nepal seven times and the prime minister once. “They say they feel some kind of fire, a positive energy around me,” she said. “The people praying to me have actually been blessed, but I don’t feel anything.”

From goddess to mortal

In recent decades , criticisms of the Kumari tradition have been mounting. The girls are considered to become mortals again when they reach puberty, when they are removed from the temple and replaced. Former Kumari “often face difficulties adjusting to normal life”, said DW. In her 1990s memoir, “From Goddess to Mortal”, ex-Kumari Rashmila Shakya described her lack of education and her struggle to re-integrate into society. Since then, the Nepali government has made it mandatory to provide a serving Kumari with an education and introduced a monthly pension of about $165 for former Kumaris, slightly above the minimum wage.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Their former status can impact their personal lives, too. Nepalese folklore also holds that men who marry a former Kumari will “suffer premature death” said The Guardian in 2001. “Few boys are willing to contemplate such a fate, it seems.”

“The Kumari is forced to give up her childhood,” said one of Nepal’s leading human rights lawyers, Sapana Pradhan-Malla. “She has to be a goddess instead. Her rights are being violated.” Nepal is a signatory to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, she said, which makes it clear that “you can’t exploit children in the name of culture”.

Harriet Marsden is a senior staff writer and podcast panellist for The Week, covering world news and writing the weekly Global Digest newsletter. Before joining the site in 2023, she was a freelance journalist for seven years, working for The Guardian, The Times and The Independent among others, and regularly appearing on radio shows. In 2021, she was awarded the “journalist-at-large” fellowship by the Local Trust charity, and spent a year travelling independently to some of England’s most deprived areas to write about community activism. She has a master’s in international journalism from City University, and has also worked in Bolivia, Colombia and Spain.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Dozens dead as typhoon slams Philippines

Dozens dead as typhoon slams PhilippinesSpeed Read The storm ravaged the island of Cebu

-

Why Gen Z in Nepal is dying over a state social media ban

Why Gen Z in Nepal is dying over a state social media banIN THE SPOTLIGHT A crackdown on digital platforms has pushed younger Nepalis into increasingly violent clashes with government forces

-

The IDF's manpower problem

The IDF's manpower problemThe Explainer Israeli military's shortage of up to 12,000 troops results in call-up for tens of thousands of reservists

-

Missionaries using tech to contact Amazon's Indigenous people

Missionaries using tech to contact Amazon's Indigenous peopleUnder the radar Wealthy US-backed evangelical groups are sending drones to reach remote and uncontacted tribes, despite legal prohibitions

-

What has the Dalai Lama achieved?

What has the Dalai Lama achieved?The Explainer Tibet’s exiled spiritual leader has just turned 90, and he has been clarifying his reincarnation plans

-

The Swedish church at the centre of a Russian spy drama

The Swedish church at the centre of a Russian spy dramaUnder The Radar The Russian Orthodox Church is accused of being an 'active tool' of Moscow's 'soft power'

-

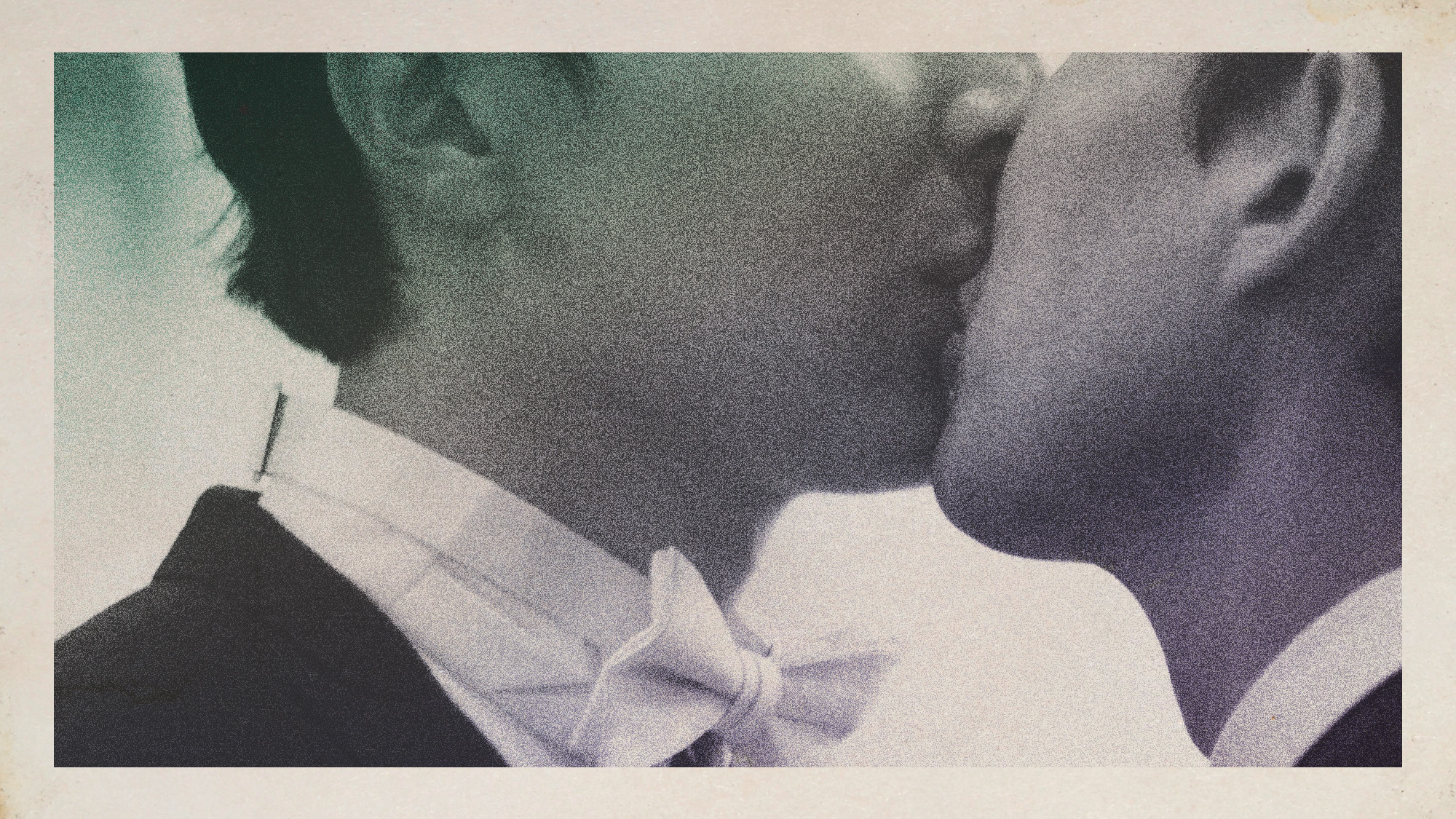

The slow fight for same-sex marriage in Asia

The slow fight for same-sex marriage in AsiaUnder the Radar Thailand joins Nepal and Taiwan as the only Asian nations to legalise LGBT unions, amid repressive regimes and religious traditions

-

Modi opens contentious Ram temple at one of India's 'most vexed religious sites'

Modi opens contentious Ram temple at one of India's 'most vexed religious sites'Talking Points Indian PM kicks off re-election campaign by affirming Hindu nationalism, while Muslim minority feel pain of history and threat of future