Why the government should fund research into finding a replacement for alcohol

Science might help us get tipsy more safely

Research into recreational drugs still carries a bad rap, following the anti-drug crusades of the Reagan years and beyond. But such research may be one of the most important scientific investigations happening today.

Here's why: the most popular recreational drugs, particularly alcohol, are atrocious. If pharmaceutical chemists could invent a less toxic replacement for alcohol, the social benefits could be enormous.

Despite the common phrase "drugs and alcohol," which seems to imply that alcohol is merely in a related category, alcohol is definitely a drug. Indeed, as Mark Kleiman writes, alcohol is more like the ur-drug: the oldest, most common, and most widely abused drug in the world.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

It's also very often terrible. It can be extremely hard on the body. Heavy long-term use damages practically every organ, especially the heart, the brain, and the liver. Chronic overuse can cause slew of different kinds of brain damage; severe memory loss; cardiovascular disease and strokes; cirrhosis of the liver; cancer of the mouth, throat, larynx, esophagus, liver, colon, and breast; high blood pressure; pancreatitis; and dozens of other problems.

Contrast that with another hard drug, heroin. Though heroin is very addictive, and a lot easier to overdose on, long-term use is largely non-toxic to the body (setting aside the risk of contaminants). Even its infamous withdrawal is not as bad. Indeed, alcohol withdrawals are perhaps the worst of any drug, with the possible exception of some benzodiazepines. Heroin withdrawal is excruciating, but severe alcoholics in withdrawal often simply die of seizures or delirium tremens.

Roughly 18 million Americans have an alcohol use disorder, and about half the country has a close family member with a current or previous alcohol addiction.

Something like a third of convicted people in jail or prison were drinking when they committed their crime, and nearly 40 percent of violent criminals. Two-thirds of domestic violence victims report alcohol was involved. That doesn't necessarily mean all those crimes would not have happened without alcohol, but given its effects on impulse control, it's safe to say it was a big factor.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Worldwide in 2012, according to the World Health Organization, alcohol caused 3.3 million deaths, or 5.9 percent of the total. But alcohol was responsible for about a quarter of all deaths among people aged 20 to 39. In the U.S., alcohol accounts for almost 90,000 deaths yearly; it is the third-place finisher among causes of preventable death.

Alcohol also has many benefits. In minor doses it has some protective effects on the cardiovascular system, and may reduce the risk of kidney stones and gallstones.

Its primary benefits are probably social, however. Alcohol lubricates gatherings. Loosened inhibitions help people strike up conversations and become friends. Dedicated communities get great pleasure out of the complex flavors of scotch, beer, wine, and other drinks. And as I will be the first to testify, a nice buzz feels pretty good! I am certainly not in favor of reinstating full-scale prohibition.

But that brings us to the question: would it be possible to discover another drug with similar properties to alcohol, but without its toxic side effects? Dr. David Nutt is working on that question right now. Like the famed drug chemist Alexander Shulgin, who developed more than 200 new psychedelic drugs, Nutt has filed for patents on some 85 different compounds, and claims to have a new one called "alcosynth" that mimics alcohol's buzz without the long-term damage. He's got another that can apparently help people sober up quickly and prevent hangovers.

Of course, any new drug needs extensive study before it could possibly be used on a wide scale. And as we've seen with alcohol or tobacco, setting up a giant profitable industry dedicated to pushing drugs on people is highly problematic. As with marijuana, stiff regulations to deliberately keep such a business small and inefficient would be a good start. The idea would be to make it cheap and available enough to stop a black market from developing, but only just barely, as cheap drugs enable addiction.

But as I argued with respect to MDMA and psychedelics, alcohol replacement is some of the lowest-hanging scientific fruit out there. Dr. Nutt is currently looking for funding to do studies on his new drugs; private foundations and governments everywhere should pony up the cash, and look for more candidates. And while there will undoubtedly be some risk involved, it's important to remember that our current situation is already very bad, with millions of people suffering and dying. A replacement drug doesn't have to be a miracle drug — just better than booze.

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.

-

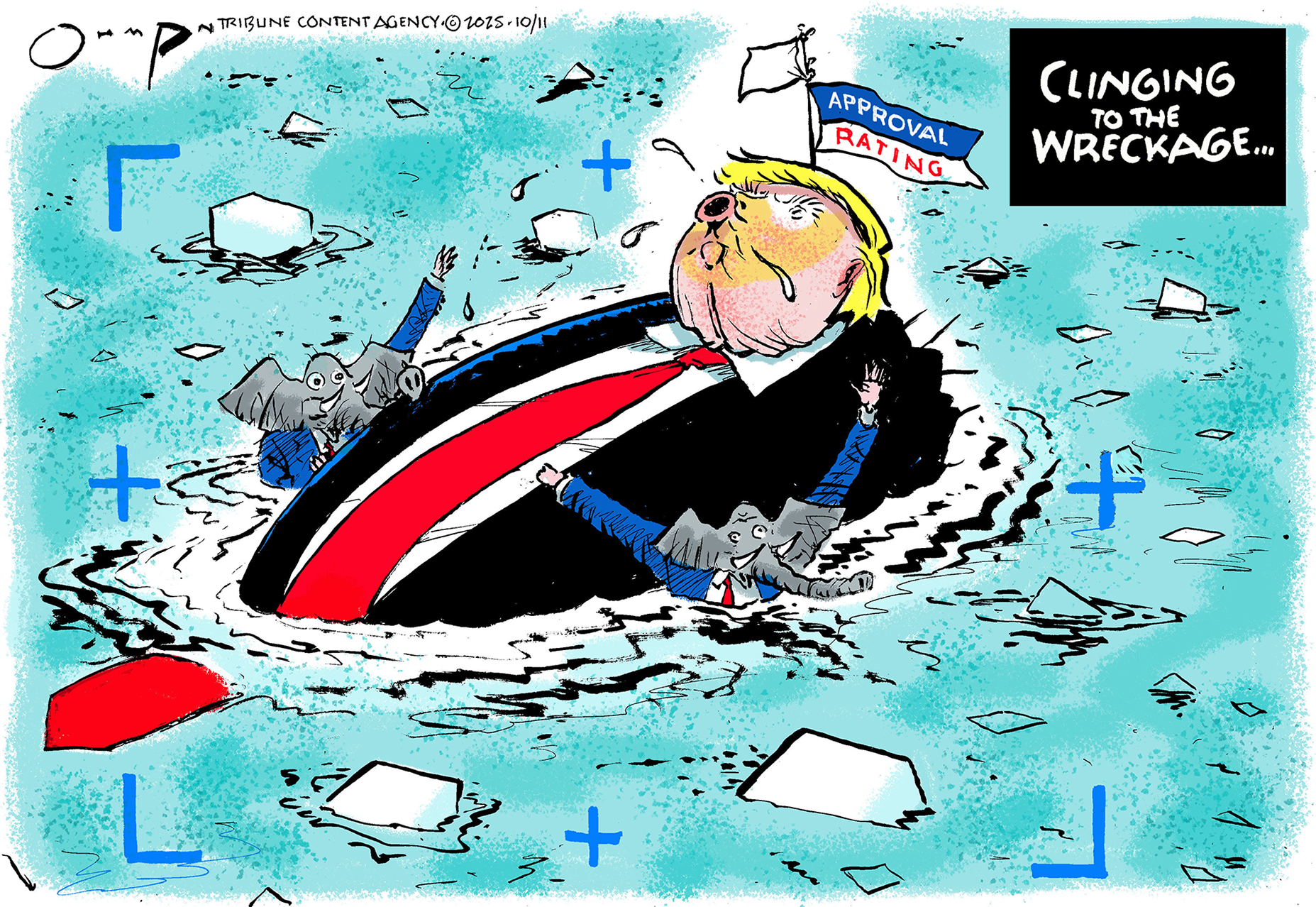

Political cartoons for December 11

Political cartoons for December 11Cartoons Thursday's political cartoons include sinking approval ratings, a nativity scene, and Mike Johnson's Christmas cards

-

It Was Just an Accident: a ‘striking’ attack on the Iranian regime

It Was Just an Accident: a ‘striking’ attack on the Iranian regimeThe Week Recommends Jafar Panahi’s furious Palme d’Or-winning revenge thriller was made in secret

-

Singin’ in the Rain: fun Christmas show is ‘pure bottled sunshine’

Singin’ in the Rain: fun Christmas show is ‘pure bottled sunshine’The Week Recommends Raz Shaw’s take on the classic musical is ‘gloriously cheering’