What the English of Shakespeare, Beowulf, and King Arthur actually sounded like

Shakespeare in Love it ain't

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Let's hop into a time machine and go back to the England of yore!

If this were a movie, no matter when we got out of the machine, we could walk up to people and start talking. It could be medieval times or the age of King Arthur's round table, and they'd just say, "Who art thou, varlet?" and we'd reply with something like, "We, uh, would-eth like-eth some beer-eth," and we'd all party. Yeah, no.

I mean, of course they have to do that in movies, because we need to understand them. But this is reality. We're going to hear what they really talked like. Ready? Buckle up!

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Shakespearean England

First stop: the early 1600s. The time of Shakespeare! Of course the English of Shakespeare and the King James Bible may seem flowery, but it's basically just an older version of what we speak now. In fact, it's what linguists call Early Modern English. But the way they spoke it was not quite what we probably expect — or what you hear in the movies. Do you imagine some Queen's English accent? Or perhaps Cockney for the lower classes? Guess what: the way they spoke it would sound to us more like a mix of Irish and pirate. Here, listen to Ben Crystal (son of linguist David Crystal) perform a sonnet in the pronunciation of Shakespeare's time:

Medieval England

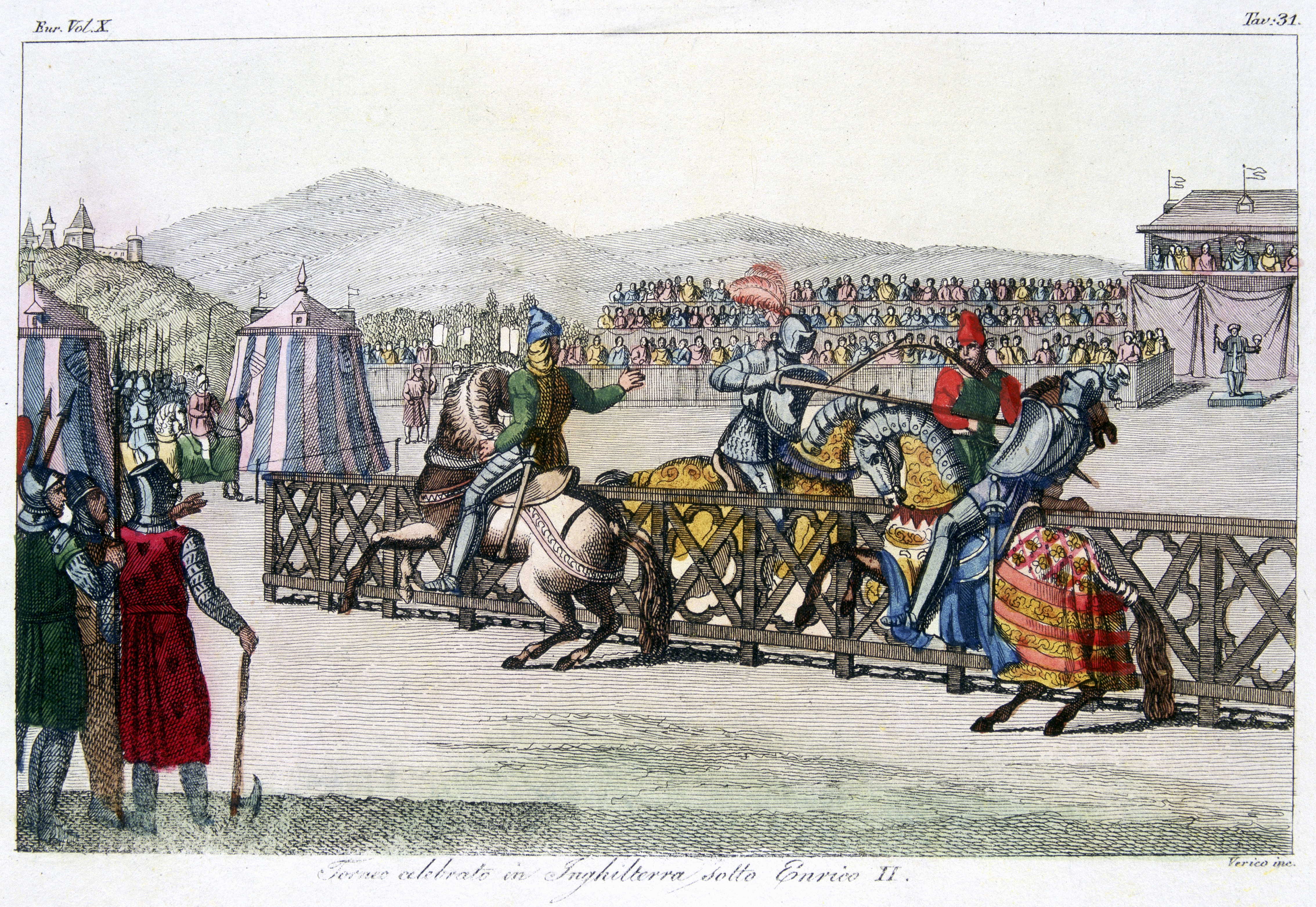

Next stop: the 1300s. That's when Geoffrey Chaucer lived. Do you remember the Canterbury Tales? Here's how it starts:

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Whan that Aprill, with his shoures sooteThe droghte of March hath perced to the rooteAnd bathed every veyne in swich licour,Of which vertu engendred is the flour

You can probably sort out what's being said, generally. It has a few differences here and there, but with a little help and attention you can figure it out. But could you carry on a conversation in it? Could you even understand it if you heard it? Here's how it sounded, as read by Diane Jones:

Let's take the time machine back just another century — still in the Middle English period — and have a listen to a song from that time, as sung by the lovely ensemble Anonymous 4:

Here's a bit of the text (the þ characters are how we used to write th):

Edi beo þu hevene quenefolkes frovre and engles blis,moder unwemmed and maiden cleneswich in world non oþer nis.

Do you reckon you could just walk into an inn and order up some meat pie and ale in a place where they spoke this version of English?

But wait, there's more. A lot more. So far, we're still after English lost most of its heavy noun inflections and complex verbal conjugations — and changed a lot of its words. We can thank invaders for that: French in the south (starting in 1066) and Scandinavians in the north (starting in the mid-800s but having more influence later on). Before they got to it, English was a whole other thing…

Old English

Old English is a bit of a misleading name. It's not understandable at all to modern English speakers; you'd have an easier time learning Dutch or Danish. Some people prefer to call it Anglo-Saxon, since it's the language that was brought over by the Angles and Saxons, invaders from northern Germany who took over Britain in the 600s.

The most famous bit of literature from the Old English period is Beowulf. I'm sure we all know the beginning of Beowulf, right? No? Well, if you don't, here it is:

Hwæt! We Gardena in geardagum,þeodcyninga, þrym gefrunon,hu ða æþelingas ellen fremedon.

We're not with Bill and Ted anymore! Come on, step out of the time machine and let's listen to the words recited by Benjamin Bagby, who sounds like he grew up then:

Nice of them to give subtitles! Now get back into the machine. We're going to the 400s and 500s, to the time of King Arthur (if he existed).

Arthurian Britain

Did King Arthur speak Old English? Noooo. Do you remember that I said the Angles and Saxons took over Britain in the 600s? Arthurian Britain was before the Germanic invaders came and made the place England (Angle-land). What Arthur and his knights of the round table, and all the other people around then and there, would have been speaking was something we now call Brythonic or Brittonic: a Celtic language. Completely unlike modern English.

So obviously you're not going to get that pint of beer, because you're not going to be able to ask for it. And these people suddenly don't look so welcoming. So we scram back into the machine and put it in forward gear… But uh-oh. It doesn't go back to modern English. It follows the people who spoke what they spoke in King Arthur's time. The Britons.

Brittonic didn't stop existing when the Anglo-Saxons invaded, you see. Anglo-Saxon didn't simply replace it. The people who spoke it retreated, some to Wales, some to Cornwall, some a little farther. Over the centuries, the language of the ones who retreated to Wales became modern Welsh, in which Llanfairpwllgwyngyll means "Parish of St. Mary in White Hazel Hollow." The language of those who retreated to Cornwall became Cornish, which was quite nearly wiped out in recent centuries, but is having a bit of a revival.

But our time machine is following the ones who kept the name of the Britons. They retreated across the English Channel — to a part of France that came to be named after them: Bretagne, or, in English, Brittany. The Celtic language spoken there, Breton, is descended from Brittonic, the language of King Arthur (with some French influence, of course). Listen to the Breton singer Nolwenn Leroy singing a Breton song about three young sailors (tri martolod yaouank):

Here are some of the lyrics (minus the repeats):

Tri martolod yaouank i vonet da veajiñGant 'n avel bet kaset betek an Douar NevezE-kichen mein ar veilh o deus mouilhet o eorioùHag e-barzh ar veilh-se e oa ur servijourez

It's about three sailors who were blown far off course. We and our time machine — and our language — know something about that now…

James Harbeck is a professional word taster and sentence sommelier (an editor trained in linguistics). He is the author of the blog Sesquiotica and the book Songs of Love and Grammar.

-

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unity

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unityFeature The global superstar's halftime show was a celebration for everyone to enjoy

-

Book reviews: ‘Bonfire of the Murdochs’ and ‘The Typewriter and the Guillotine’

Book reviews: ‘Bonfire of the Murdochs’ and ‘The Typewriter and the Guillotine’Feature New insights into the Murdoch family’s turmoil and a renowned journalist’s time in pre-World War II Paris

-

Witkoff and Kushner tackle Ukraine, Iran in Geneva

Witkoff and Kushner tackle Ukraine, Iran in GenevaSpeed Read Steve Witkoff and Jared Kushner held negotiations aimed at securing a nuclear deal with Iran and an end to Russia’s war in Ukraine