How Indiana's religious freedom law empowers businesses at the expense of everyday Americans

Contrary to Republican wisdom, corporations aren't people

You may have heard that Indiana passed its version of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act. It's one of 20 states that now have such a law. There's a federal version as well, passed by a 97-3 vote in the Senate and signed into law by President Clinton way back in 1993. But only Indiana's RFRA has become a hugely controversial deal, with opponents saying it opens the door to discrimination against LGBT Americans and other minorities.

So what gives? Why haven't we have heard about RFRAs before now?

It boils down to this: Indiana's RFRA actually contains crucial differences, and recent court decisions may push all RFRAs to be read in the way Indiana's law is explicitly written. That change carries consequences for the balance of power between businesses and wealthy elites on the one side, and everyday customers and employees on the other.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The headline purpose of your average RFRA is simple: The government can only impose on a person's religious freedom when a compelling government interest is at stake, and when no simpler or more efficient route is available to achieve that interest.

Indiana's law brings two key innovations. First, it explicitly includes for-profit businesses as "persons" who can claim a right to the free exercise of religion. No other RFRA save South Carolina's includes such language. Second, Indiana's RFRA doesn’t just protect people from the federal government — it protects them from private lawsuits as well. No RFRA other than Texas' does this.

Furthermore, with last year's Hobby Lobby case, the Supreme Court found RFRA protections applied to "closely held" corporations, but not all for-profit businesses. That took the federal RFRA a big step towards functioning like the Indiana RFRA, despite the differences in language. There's also a growing body of jurisprudence — albeit still hotly contested — that the federal RFRA can be read as protecting persons in private lawsuits.

Jurisprudence is a complex beast. So it can take a while for the full consequences of particular readings to percolate into the public consciousness. By all accounts, the bipartisan coalition that passed the federal RFRA would never have held if the Democrats could have known the uses to which it's now being put. "That coalition would have exploded like someone hitting a watermelon with a shotgun," Barry Lynn, of Americans United for Separation of Church and State, told MSNBC in 2014.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

"Once you went into the commercial sector, you couldn't claim a religious liberty to discriminate against somebody," added Rep. Jerry Nadler (D-N.Y.), one of the lawmakers behind the federal RFRA. "That never came up. It was completely obvious we weren't talking about that."

It's worth remembering that what sparked the original law was two members of a Native American Church in Oregon getting fired from their jobs and denied unemployment benefits because they used peyote in their religious rituals. They argued this violated their religious freedom, and the Supreme Court decided otherwise. A public outcry ensued, and the federal RFRA was the result. Its intent was to protect the relatively powerless (two everyday Native American workers) from an entity with considerable and capricious power (the government). And if you go through the list of instances where people used RFRA laws to defend themselves, it's the same dynamic at work.

The new shift arguably turns the purpose of RFRA on its head. It takes a framework to protect everyday Americans, and hands it over to businesses — powerful and capricious entities themselves — as a justification for them to wiggle out of legal obligation to their workers and customers, most obviously the obligations in anti-discrimination law.

There's a truth buried in anti-discrimination law we'd do well to remember: Unlike your home, your business is not your castle. It's a public trust. No business could exist without the laws and legal frameworks to govern contract and property law, which we all pay to maintain. Nor could they get by without roads and water infrastructure and all the rest. They could not operate if their employees were uneducated, or if they were always getting sick. Many could not operate if their customers did not have adequate purchasing power, which is distributed in no small part by the social safety net.

Furthermore, because we all rely on the economy as part of our social fabric, and because we as Americans value both freedom and equality, any place of business has certain moral obligations to deal with its customers and employees by certain basic standards — regardless of whether the business' owners approve of that person's race, religion, sexual orientation, or whatever. That's because of the considerable power business themselves wield, with the ability to threaten the freedom of everyday Americans.

That's the point that the defenders of Indiana's RFRA are probably most deeply opposed to. They argue that the law does not guarantee a business or corporation a win in court, but is simply available as a possible defense. But initiating or defending against a lawsuit are inescapably economic acts, requiring time, money, resources, and influence. It takes an incredible leap to think the average American customer or employee could mount that kind of challenge against even a small business, much less a major corporation on the scale of Hobby Lobby. It requires an even more incredible leap to think that two Native American drug counselors and Hobby Lobby are all entities of equal vulnerability, both with religious freedom rights equally in danger of being trampled by the powerful.

But those leaps are being made. And they're slowly transforming the language of RFRA laws — originally intended as shields for the powerless — into swords for the powerful to cut themselves loose from their obligations to the rest of us.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

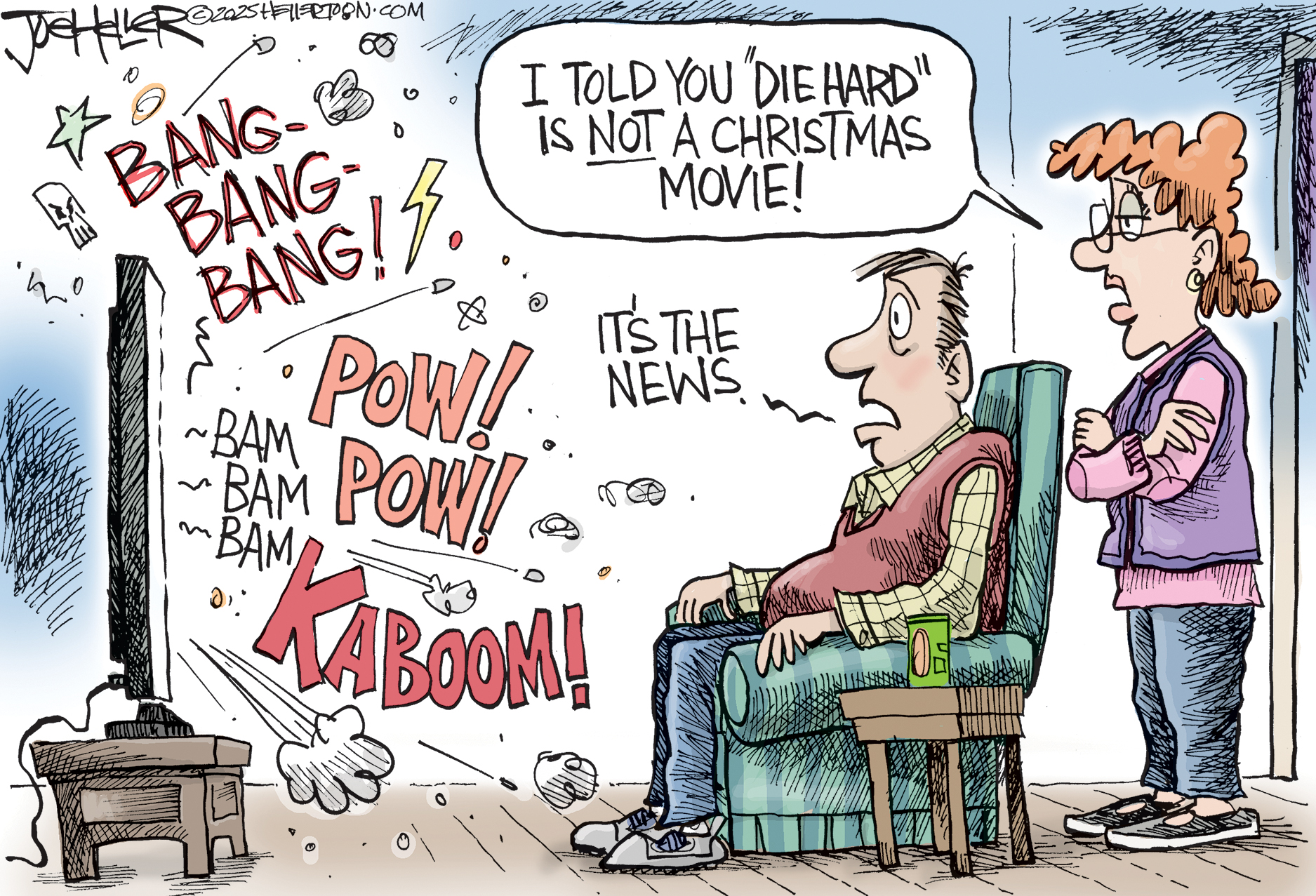

Political cartoons for December 21

Political cartoons for December 21Cartoons Sunday’s political cartoons include Christmas movies, AI sermons, and more

-

A luxury walking tour in Western Australia

A luxury walking tour in Western AustraliaThe Week Recommends Walk through an ‘ancient forest’ and listen to the ‘gentle hushing’ of the upper canopy

-

What Nick Fuentes and the Groypers want

What Nick Fuentes and the Groypers wantThe Explainer White supremacism has a new face in the US: a clean-cut 27-year-old with a vast social media following