Brazil's economic catastrophe

Brazil used to have one of the world's fastest-growing economies, but now it's a basket case. What happened?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Brazil used to have one of the world's fastest-growing economies, but now it's a basket case. What happened? Here's everything you need to know:

When did the shift begin?

Just five years ago, Brazil was being touted as an emerging new world power, with a booming economy growing by 7 percent a year, a burgeoning middle class, and major oil reserves discovered off the coast. The ruling Workers Party, which took power in 2003 under then President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, lifted more than 40 million Brazilians up to the middle class, partly through a cash-transfer program known as a "family stipend" and partly by making it easier for workers to get credit to buy cars, washing machines, and other consumer goods. But the boom turned out to be a bubble that has now burst. The economy has stagnated and is about to tip into its worst recession in 25 years. Inflation has soared to 8 percent, eating away people's paychecks, and widespread corruption has undermined the economy. The country's once popular president, Dilma Rousseff, is now widely scorned as corrupt and incompetent, with huge throngs of protesters regularly filling the streets to denounce her. Lawmakers are threatening to impeach her over an alleged $2.1 billion embezzlement scheme at the state oil company, Petrobras. "There is a process of economic, social, and moral collapse underway," said Sen. Ronaldo Caiado, a Rousseff opponent.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What caused the collapse?

Brazil was hit by a perfect storm of economic disasters. It is still a commodities-producing country, heavily dependent on exports of its crops and natural resources. In the past year, though, the economies of the countries that buy its goods, particularly China and Germany, have slowed, drying up demand. And the prices of its main exports have plummeted. The oil price plunge has hit Brazil hard, while sugar, coffee, and soybean prices are all down by as much as 33 percent. With government debt piling up, the currency, the Brazilian real, has lost a quarter of its value this year. Drought has produced an acute shortage of water — in São Paulo, some neighborhoods get running water just every other day — and since most of Brazil's energy is hydroelectric, that means an energy shortage and soaring electricity prices.

What's the government doing?

Its hands are largely tied, thanks to entrenched corruption and fiscal mismanagement. Government debt has risen dramatically, and interest rates have climbed past 13 percent, making it too expensive to borrow additional money to stimulate the economy. Credit-rating agency Fitch puts Brazil's bonds just one tick above junk. So Rousseff is trying to heal the economy by belt-tightening — but for people to accept lower salaries and benefits, they must have faith in government institutions, and Brazil is notoriously corrupt. In 2005, a vote-buying scandal implicated top officials in the Workers Party, who were allegedly buying off legislators to support Lula's policies and legislation. Rousseff has proposed a bill to limit the power of prosecutors to go after corrupt politicians — further enraging the public. Now the country is engulfed in the even larger scandal involving Petrobras.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

What happened at Petrobras?

Federal police began an investigation in 2013 when they found that a suspected money launderer had given an expensive luxury car to a top Petrobras exec, Paulo Roberto Costa. The investigation, called Operation Car Wash, found that Petrobras has been overpaying contractors by the hundreds of millions at least since 2006 and funneling some of the cash back to President Rousseff's Workers Party and some to corrupt business leaders, who've pocketed tens of millions. Petrobras stock has lost half its value, and since it's a state-owned company, the taxpayers are on the hook. A cartel indictment against the country's top construction and engineering firms is imminent. Costa has already been convicted of belonging to a criminal organization, and more than 100 other members of Brazil's business and political elite have been arrested — including the treasurer of Rousseff's party.

Does Rousseff face charges?

No evidence has emerged to implicate her, although she was chairwoman of Petrobras for eight years before becoming president. But since her party benefited from the kickbacks, her approval rating is now just 9 percent — the worst ever for a Brazilian president. In March, a million people poured into the streets of Rio and other cities, calling for her to resign. Brazilians fear that, just as in the 2005 vote-buying scandal, ultimately nobody will be held accountable.

What's next?

As public sector workers face cuts in benefits and salaries, they are striking all across the nation. Police have met these protests with violence — in the southern state of Paraná, cops unleashed tear gas and rubber bullets on a teachers' protest and injured more than 200 people — sparking more outrage and more protests. Brazil may be reaching its boiling point. "When families go to the supermarket, they can't fill up their carts like they used to with the same amount of money," Brazilian pollster Mauro Paulino told the Financial Times (U.K.). "And the news is all about corruption. They're short of money and at the same time they are being told they have been robbed."

Brazil's richest pauper

Just two years ago, Eike Batista was Brazil's richest man and the seventh-richest person on the planet, worth $34.5 billion. He had a private fleet of yachts and jets. Now he is more than a billion dollars in debt. His downfall is Brazil's in microcosm. A gold-mining baron, Batista moved into oil and gas in 2007, and his initial explorations promised some $1 trillion in oil and gas deposits 37 miles off the coast, in the Atlantic Ocean. The value of Batista's oil company soared, and the firm borrowed heavily on that strength, only to be unable to pay when the oil proved tough to get at and far less plentiful than Batista had estimated. His other companies were in commodities, which have collapsed worldwide. Now Batista is nearly bankrupt and on trial for insider trading. "Theoretically, I'm at zero," he recently said. "But I'll be back." That's what Brazil is hoping for itself, too.

-

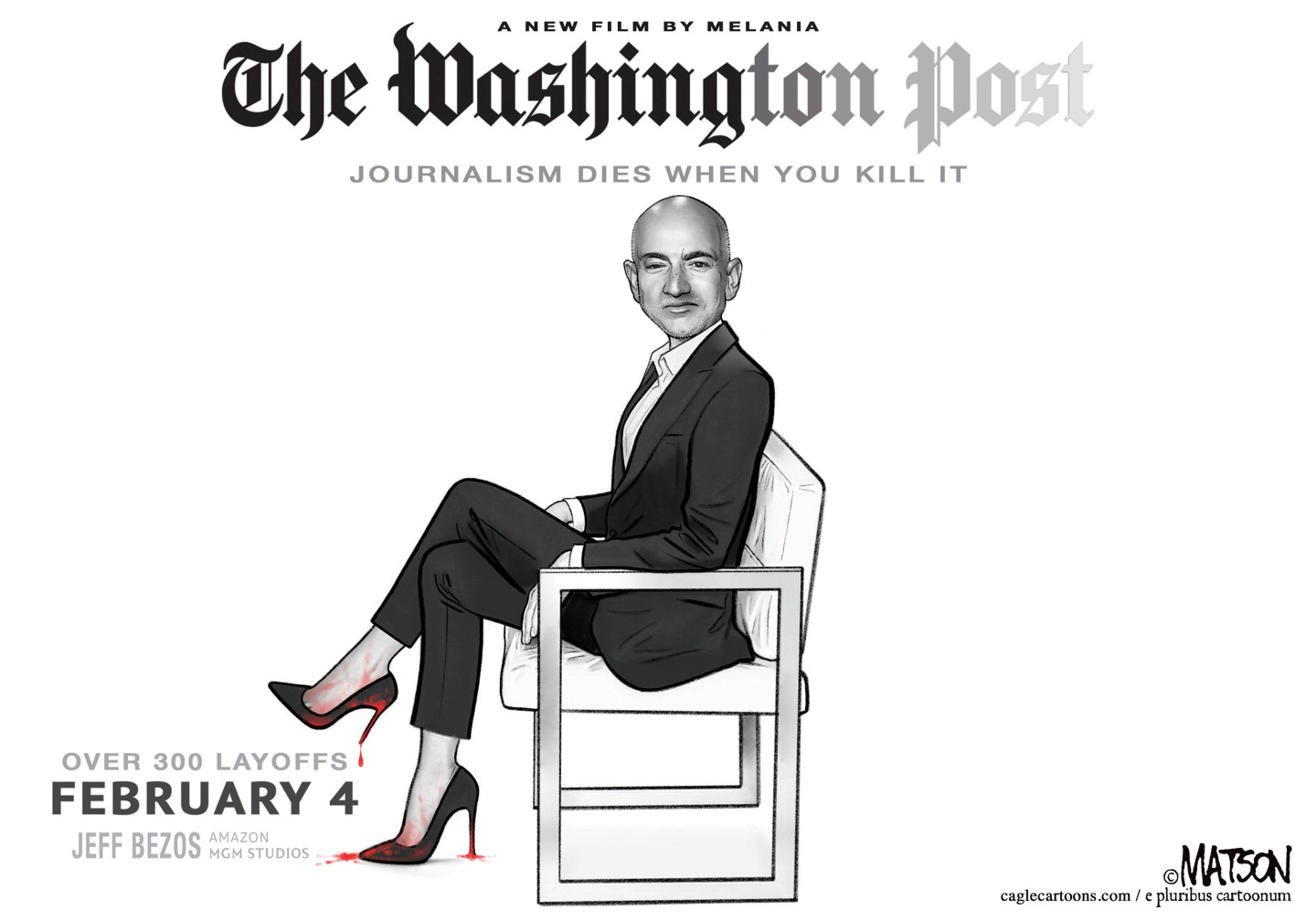

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'Cartoons Artists take on a girlboss, a fetching newspaper, and more

-

The fall of the generals: China’s military purge

The fall of the generals: China’s military purgeIn the Spotlight Xi Jinping’s extraordinary removal of senior general proves that no-one is safe from anti-corruption drive that has investigated millions

-

Why the Gorton and Denton by-election is a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’

Why the Gorton and Denton by-election is a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’Talking Point Reform and the Greens have the Labour seat in their sights, but the constituency’s complex demographics make messaging tricky

-

The pros and cons of noncompete agreements

The pros and cons of noncompete agreementsThe Explainer The FTC wants to ban companies from binding their employees with noncompete agreements. Who would this benefit, and who would it hurt?

-

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contraction

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contractionThe Explainer The sharpest opinions on the debate from around the web

-

The death of cities was greatly exaggerated

The death of cities was greatly exaggeratedThe Explainer Why the pandemic predictions about urban flight were wrong

-

The housing crisis is here

The housing crisis is hereThe Explainer As the pandemic takes its toll, renters face eviction even as buyers are bidding higher

-

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkers

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkersThe Explainer Show up for your colleagues by showing that you see them and their struggles

-

What the stock market knows

What the stock market knowsThe Explainer Publicly traded companies are going to wallop small businesses

-

Can the government save small businesses?

Can the government save small businesses?The Explainer Many are fighting for a fair share of the coronavirus rescue package

-

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shock

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shockThe Explainer This could be a huge problem for the entire economy