How the Democrats became the new party of liberty

On balance, the Democrats are offering Americans more freedoms than the Republicans

In the U.S., liberty is a cherished ideal dating back to at least the Boston Tea Party, and both major parties have tried to claim its mantle. But the Republican Party has been more successful at it in recent decades, starting with Ronald Reagan's election in 1980. That election ushered in the GOP as we know it today — anti-tax, anti-spending, anti-regulation, aggressive on foreign policy — and marks the point at which conservatives were able to convince Americans that their ideas were boons to freedom.

Last week, the balance finally shifted, after national Democrats almost universally embraced the Supreme Court's decision recognizing a constitutional right to same-sex marriage and national Republicans almost universally denounced it. On balance, the Democrats are now the party of freedom and liberty.

How did this happen? Let's start with something relatively anodyne: trains and buses. Before 1980, Republicans had emphasized their support for public transportation, Marc Fisher noted in The Washington Post in 2012, in an examination of more than 50 years of GOP presidential platforms. In 1980, the Republican platform included this rhetorical and policy pivot: "Republicans reject the elitist notion that Americans must be forced out of their cars. Instead, we vigorously support the right of personal mobility and freedom as exemplified by the automobile."

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

President Richard Nixon proudly ushered in the Environmental Protection Agency and signed the Clean Water Act, but seven years after he left office in disgrace, his party declared "war on government overregulation."

By the time the Tea Party appropriated the mantle of liberty in the long, hot summer of 2009, "freedom" meant no government intervention in banking, the housing market, and auto company collapses; less government in health care markets; fewer gun ownership restrictions; and — as one origin story for the name Tea Party suggests — fewer taxes, since the Tea Partiers felt Taxed Enough Already.

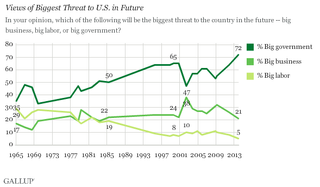

Since Reagan, Democrats have generally been seen as the party of Big Government. And Big Government has been increasingly unpopular since the Reagan revolution, according to Gallup:

[Gallup]

Big Government hit a first big low point under Bill Clinton, about the time Clinton declared that "the era of Big Government is over" in 1996. But Democrats weren't always the party of Big Government.

In the 1860s, Abraham Lincoln's Republican Party was the party that promoted a strong, activist federal government, and the Democrats pushed for limiting the central government's role, says political scientist Eric Rauchway at The Chronicle of Higher Education. When William Jennings Bryan became the Democratic standard-bearer in 1896, the party started embracing a larger central government, and the Republicans didn't take the opposite side until around Franklin Roosevelt's first re-election in 1936, in the thick of his New Deal.

Under John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, things got muddled, freedom-wise. The federal government increasingly sided with black Americans fighting for basic civil rights, mandating freedom through government intervention. The New Deal gave way to the Great Society, notably Medicare. Americans got a new payroll tax, but also freedom from abject poverty in their golden years.

And as the post-Nixon Republican Party started advocating for fewer taxes and less regulation, the socially conservative wing of the party started pushing for curtailed personal liberties. In 1976, the GOP platform said the party was split on the issue of abortion rights, calling it "undoubtedly a moral and personal issue," Fisher noted at The Washington Post. But by 1980 the platform was pushing for a constitutional amendment outlawing abortion.

The 1992 platform is when social conservatives really got traction. It was the first one to mention same-sex relationships, solidly rejecting not only gay marriage but also adoption and foster parenting by gay couples. It also sought to limit choices in entertainment, claiming that "the media, the entertainment industry, academia, and the Democrat [sic] Party are waging a guerrilla war against American values."

After the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, the GOP took another step back from personal liberties, pushing through the Patriot Act and instituting covert domestic surveillance practices that only came to light near the end of Bush's second term. Under Bush, the TSA got a lot more invasive and particular before you could board an airplane. No Child Left Behind did a lot to shrink or eliminate children's free time at school in favor of more standardized testing.

So, here we are, nearing the end of Obama's second term. Let's tally the score.

When it comes to liberty, Democrats generally favor the freedom for gay people to get married, a less invasive national security/surveillance state, greater choice regarding abortion and contraception, loosened marijuana laws, less restrictive voting laws, less censorship of popular entertainment, more freedom of movement for immigrants, and stronger workplace protections to encourage freedom of leisure time (or fair compensation for giving it up).

For Republicans, liberty generally looks like fewer taxes, less restrictive gun laws, less censorship of political or "hate" speech, less regulation of markets, less regulation of business, more freedom to choose between K-12 schools (with government vouchers), fewer restrictions on money in politics, and the freedom to not have health insurance or to opt for minimalist coverage.

And that's just if you keep score by the libertarian handbook. How do you count freedom from fear of medical bankruptcy, though, or fear of harassment by people who antagonize women or minorities? Or how about the liberty to pray in public schools or the freedom to refuse to serve a customer you don't approve of based on sexual orientation? Are breathing clean air and drinking clean water essential freedoms? How about inexpensive gas?

FDR, the godfather of the Democratic shift to Big Government solutions, outlined four basic, universal freedoms in a 1941 speech, and along with the freedom of speech and freedom of worship he included freedom from want and freedom from fear.

So here's what tips the balance for me. When you look at the freedoms Republicans proffer, they tend to be economic, often favoring businesses or individual material needs. Money and guns are a type of freedom, but they pale compared to personal liberty, like marrying the person you love or trusting that police officers can't harass or harm you with impunity because of the color of your skin.

To put it another way, Democrats want to let you be the person you are and Republicans want to get the government out of your wallet. Freedom is not, as Kris Kristofferson* wrote, another word for nothing left to lose. It's the liberty to be yourself, make your own decisions, and enjoy a reasonable measure of privacy and a reasonable hope for safety. Today, in 2015, the party that comes closer to that ideal is the Democratic Party.

*[Note: An earlier version of this story incorrectly suggested that Willie Nelson wrote the song "Me and Bobby McGee," not Kris Kristofferson.]

Create an account with the same email registered to your subscription to unlock access.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Peter has worked as a news and culture writer and editor at The Week since the site's launch in 2008. He covers politics, world affairs, religion and cultural currents. His journalism career began as a copy editor at a financial newswire and has included editorial positions at The New York Times Magazine, Facts on File, and Oregon State University.

-

Italian senate passes law allowing anti-abortion activists into clinics

Italian senate passes law allowing anti-abortion activists into clinicsUnder The Radar Giorgia Meloni scores a political 'victory' but will it make much difference in practice?

By Chas Newkey-Burden, The Week UK Published

-

Magazine interactive crossword - May 3, 2024

Magazine interactive crossword - May 3, 2024Puzzles and Quizzes Issue - May 3, 2024

By The Week US Published

-

Magazine solutions - May 3, 2024

Magazine solutions - May 3, 2024Puzzles and Quizzes Issue - May 3, 2024

By The Week US Published

-

Arizona court reinstates 1864 abortion ban

Arizona court reinstates 1864 abortion banSpeed Read The law makes all abortions illegal in the state except to save the mother's life

By Rafi Schwartz, The Week US Published

-

Trump, billions richer, is selling Bibles

Trump, billions richer, is selling BiblesSpeed Read The former president is hawking a $60 "God Bless the USA Bible"

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

The debate about Biden's age and mental fitness

The debate about Biden's age and mental fitnessIn Depth Some critics argue Biden is too old to run again. Does the argument have merit?

By Grayson Quay Published

-

How would a second Trump presidency affect Britain?

How would a second Trump presidency affect Britain?Today's Big Question Re-election of Republican frontrunner could threaten UK security, warns former head of secret service

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

'Rwanda plan is less a deterrent and more a bluff'

'Rwanda plan is less a deterrent and more a bluff'Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

By The Week UK Published

-

Henry Kissinger dies aged 100: a complicated legacy?

Henry Kissinger dies aged 100: a complicated legacy?Talking Point Top US diplomat and Nobel Peace Prize winner remembered as both foreign policy genius and war criminal

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Last updated

-

Trump’s rhetoric: a shift to 'straight-up Nazi talk'

Trump’s rhetoric: a shift to 'straight-up Nazi talk'Why everyone's talking about Would-be president's sinister language is backed by an incendiary policy agenda, say commentators

By The Week UK Published

-

More covfefe: is the world ready for a second Donald Trump presidency?

More covfefe: is the world ready for a second Donald Trump presidency?Today's Big Question Republican's re-election would be a 'nightmare' scenario for Europe, Ukraine and the West

By Sorcha Bradley, The Week UK Published