In 2015, America has a labor force from the 1970s. That's bad.

The headline numbers suggest the labor market is healing itself. But a closer look reveals a deeper wound.

Reporting on the monthly jobs numbers is a little like reporting on Sisyphus. According to Greek mythology, Sisyphus was condemned by the gods to eternally roll a boulder up a hill, only to watch it roll back down again. Similarly, any journalists covering his efforts would have to report a modest gain, only to remind readers of the utterly futile big picture.

OK, the Bureau of Labor Statistics' (BLS) reports aren't that bad. But they aren't far off either.

Last Thursday, for instance, saw 223,000 jobs added to the economy and the unemployment rate dip to 5.3 percent. In fact, we've now seen 57 months of straight job growth — the longest single stretch since World War II.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

And yet, seven years after the Great Recession, we still haven't repaired the economy. To return to the same level of employment we had before the collapse (accounting for population growth), and to do so by the summer of 2017, we need to be adding 246,000 jobs a month. This latest report actually revised May and April's gains downward, so the latest three-month average is 221,000 jobs per month.

More fundamentally, the two clearest indicators of the health of American jobs are the rates of growth for average hourly earnings and inflation. They signal when employers are facing truly bottom-up pressure to offer workers better deals, because everyone who wants a job can get one. But the rate of average wage growth plummeted after 2008, and has been bouncing around at 2 percent ever since — essentially flatlined. The inflation rate has struggled to even reach 2 percent, the Federal Reserve's explicit target.

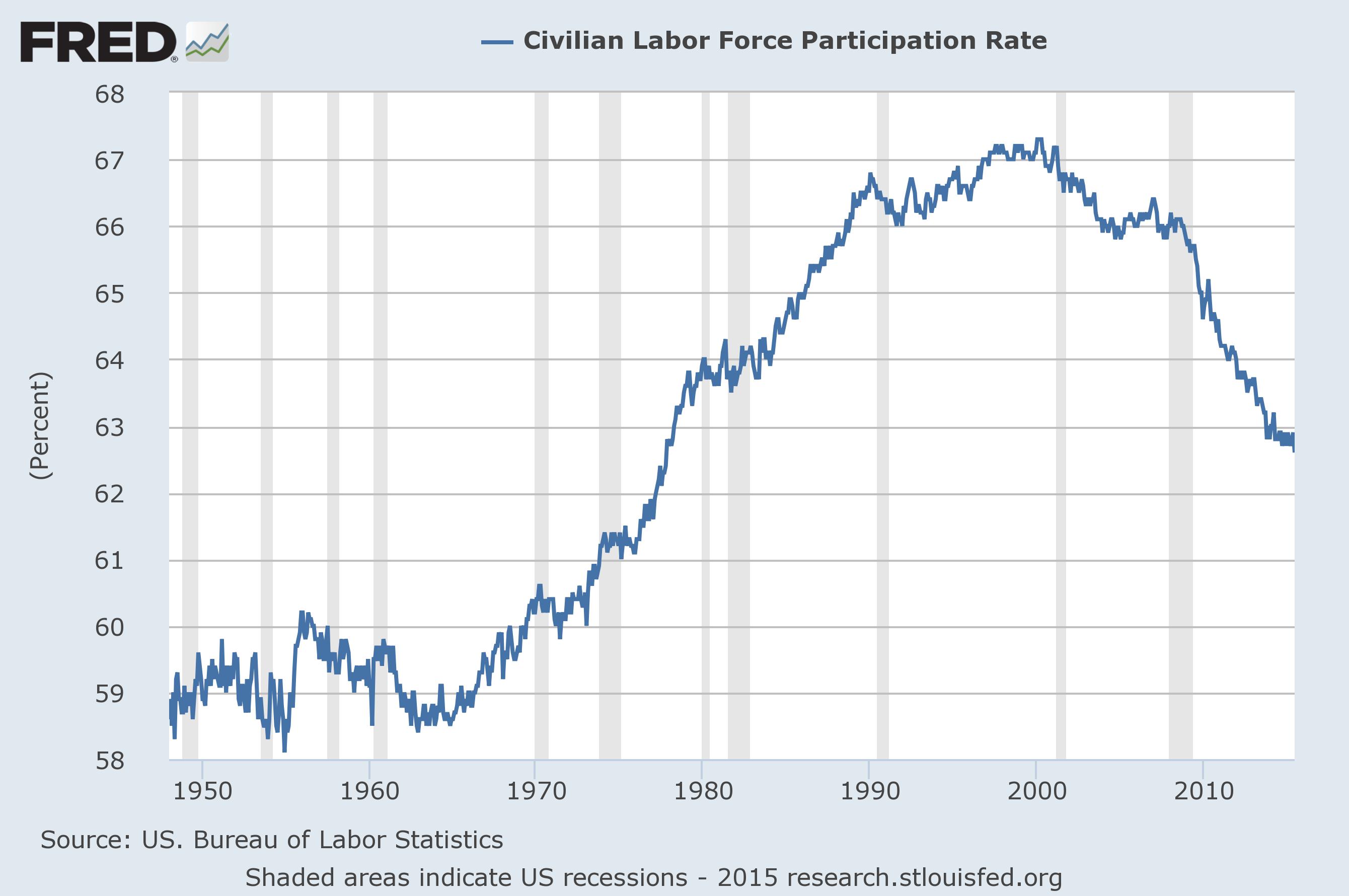

So what's going on? The first clue in the jobs report is the labor force participation rate, which is the percentage of Americans who have a job (out of everyone 16 and over who either has a job or is actively looking for one). That indicator peaked in the boom of the late 1990s at 67 percent. Then it got wobbly after 2001, fell of a cliff after 2008, and has slowly eroded since. For June it was at 62.6 percent, the lowest it's been since the late 1970s.

In fact, it fell from 62.9 percent in May, and that drop pretty much explains June's seemingly positive fall in the unemployment rate to 5.3 percent. (The rate is calculated as a share of the labor force. So if the labor force shrinks but unemployment stays steady, the unemployment rate still goes down.)

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Now, labor force participation is still higher than it was mid-century, so maybe this isn't such a big deal? Well, you see that big run-up in labor force participation after 1960? That's the entrance of women into the work world. Between 1960 and 1980, we went through a cultural shift that significantly expanded the pool of labor available in the job market.

There's nothing wrong with that pool shrinking again, but only if it was something we meant to do. We could have undertaken policies to shrink the work week, or to allow people to retire earlier, or to increase the amount of income they get from the government.

But we didn't do any of that as a society. Most families have two earners now, but both earners have to work full-time just to keep up with previous living standards. Families with only one earner tend to be poorer these days, both because they have less income and because they can't afford the child care expenses that would free up the second parent to work.

That late 1990s peak at 67 percent was also the last time wages for workers at every income level rose together. Since we haven't fundamentally altered the structure of our economic policy since then, it's fair to say that peak is what a healthy economy looks like.

You can see the problem in other measures, too. The U-6 unemployment rate counts the official unemployed, people working part-time but who want to work full-time, and people who have given up looking for jobs. It soared to 17 percent after 2008. Seven years later, it's at 10.5 percent, which is higher than it's been since the early 1990s.

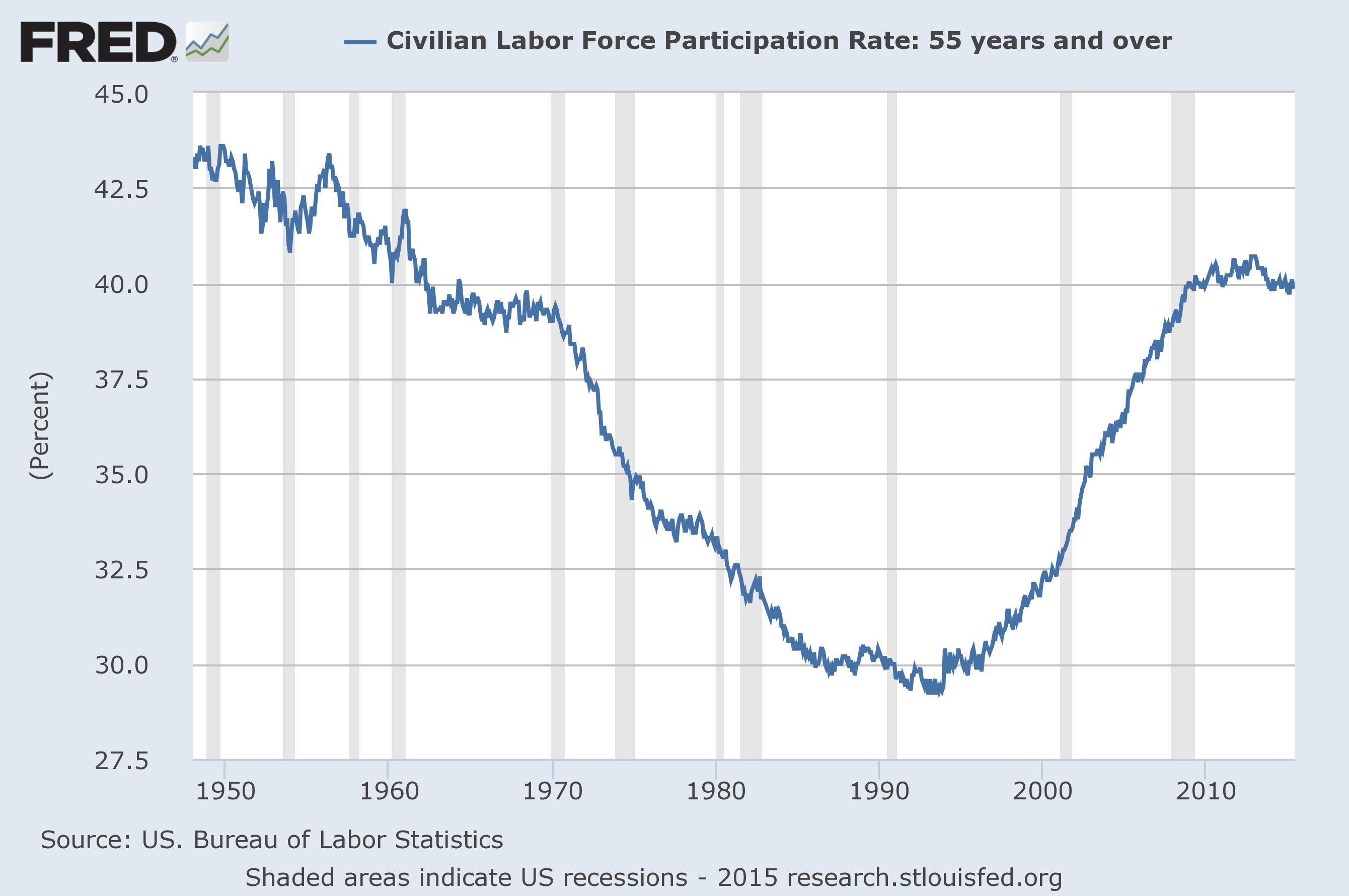

Or you can look at labor force participation amongst the 55-and-over crowd, which has gone up since 1990. We may have more older people overall, and thus more retirements, which is part of why the headline labor force participation rate is dropping. But the percentage of older people who are sufficiently scared about their future that they want to keep earning has increased.

Finally, there's the percentage of people between ages 25 and 54 who are employed. That number excludes people who might be students and people who might be retired, so it's really the core of the work force. It's headed up, but it's still well below its pre-2008 peak, which in turn was well below its late 1990s peak.

One of the crucial things to remember about inequality is that denying Americans work is one of the best ways to drive it up. Inequality stopped rising in the late 1990s because work was plentiful. If someone didn't like the deal an employer was offering, they could just go find another deal.

But in this new world, jobs for the lower class are far harder to come by, and that loss of bargaining power is cascading up the income ladder. These days, you can get someone with a BA for what you used to pay for someone with a high school degree. And you can get a worker with a mater's degree for what you'd use to pay a worker with a BA. Americans aren't just attached to the economy in a different way from before, they're attached in a fundamentally worse way: one that comes along with lower incomes, more insecurity, and jobs that are just harder to find.

In other words, this isn't a reshuffling. It's a rot.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

The Icelandic women’s strike 50 years on

The Icelandic women’s strike 50 years onIn The Spotlight The nation is ‘still no paradise’ for women, say campaigners

-

Mall World: why are people dreaming about a shopping centre?

Mall World: why are people dreaming about a shopping centre?Under The Radar Thousands of strangers are dreaming about the same thing and no one sure why

-

Why scientists are attempting nuclear fusion

Why scientists are attempting nuclear fusionThe Explainer Harnessing the reaction that powers the stars could offer a potentially unlimited source of carbon-free energy, and the race is hotting up