How the Iran nuclear accord underscores America's weakness

The deal isn't a triumph. It isn't a defeat either. It simply reflects the reality of the Obama era.

President Obama finally has his deal with Iran. The contents of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), as it is known, are probably a disappointment even to the administration and a provocation to its critics, especially Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. It is going to take weeks of public debate among experts to figure out the implications of the nearly 100-page agreement, so take everything said over the next week with some caution.

But at the very base level, we know this: The Iranian regime gets relief from sanctions. The United States and its partners get some diminishment of Iran's nuclear capability, some visibility of its nuclear development through an inspections regime, and a delay on the development of weapons. The deal isn't a treaty, and so Congress likely does not have the power to stop its implementation. But because it isn't a treaty, a future president has some latitude in re-interpreting or scuttling the deal.

The Obama administration is selling this accord with a wildly irresponsible line that the only other option is war with Iran. Republican critics, meanwhile, say that the deal is worse than no deal, though they have little to say about how sustainable a sanctions regime against Iran would be in the long run. Anschel Pfeffer, writing in Haaretz, has the best of the argument, asserting that the JSPOA is neither historic nor catastrophic:

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Stripping away the rhetoric and hysteria, the professional view in Israel's security establishment toward the Iranian accord has for many months now been one of pragmatic skepticism. The JCPOA won't drastically change the geopolitical balance in the region in the short term. Iran remains on the threshold of becoming a nuclear threshold state — and if it sticks to the agreement, which for now it has a clear incentive to do, it will remain at that step for a decade or more. [Haaretz]

The agreement does not constrain the Saudis from harassing Iran and its clients. It does not limit Israel's ability to strike at nuclear facilities it deems an existential threat. It has provisions that allow the U.S. and its allies in Europe to re-impose sanctions without the say-so of Russia or China. Just as it will take weeks to tease out every nuance of the deal, it is likely to take years to see if it is sustainable in practice.

Obama's Republican critics have reflexively called him weak and aloof when it comes to the Middle East. But the truth is that Obama's foreign policy mistakes in that region were mostly the result of promiscuous and ill-conceived intervention. Obama's administration extended and exacerbated a civil war in Syria, but never found a side it was capable of supporting in victory. It knocked over a regime in Libya, and that nation is now a playground for terrorists.

JCPOA does not give American hard-liners what they want: an Iran that is forbidden from pursuing nuclear weapons indefinitely. But it forestalls what they most fear, Iran developing nuclear weapons while it is fully isolated from the West.

The disappointment with the deal is really a disappointment with the weakened position of the United States and the limits of its power. The U.S. is already stretched across the region: It is engaging ISIS, dealing with the partial or full disintegration of at least three states (Libya, Syria, and Iraq), and keeping the lid on a war in Yemen sponsored by our ally Saudi Arabia. Keeping up pressure on Iran also means keeping the Russians and Chinese engaged on the Middle East, rather than dealing with issues in East Asia or Eastern Europe.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The United States backed down so often that the JCPOA cannot be considered an unambiguous victory — but it was also not a defeat for Obama, either. It gives a future president leverage. It allows allies to rally around certain benchmarks and regroup in case of renewed confrontation with Iran over its nuclear program. And it lets all the players — the United States, Europe, Russia, and Iran itself — deal with issues closer to home.

Michael Brendan Dougherty is senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is the founder and editor of The Slurve, a newsletter about baseball. His work has appeared in The New York Times Magazine, ESPN Magazine, Slate and The American Conservative.

-

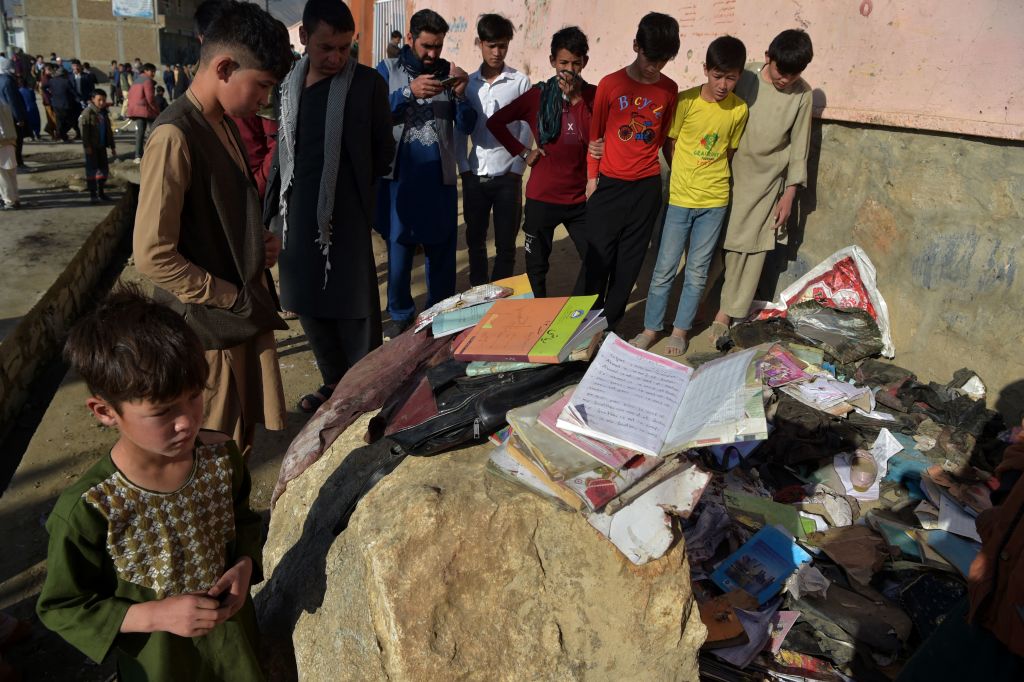

Bombing at girls' school in Kabul kills at least 50, including students

Bombing at girls' school in Kabul kills at least 50, including studentsSpeed Read

-

Garland says DOJ is 'pouring its resources' into stopping domestic terrorists 'before they can attack'

Garland says DOJ is 'pouring its resources' into stopping domestic terrorists 'before they can attack'Speed Read

-

Suspected Israeli cyberattack on Iranian nuclear site complicates U.S.-Iran nuclear deal talks

Suspected Israeli cyberattack on Iranian nuclear site complicates U.S.-Iran nuclear deal talksSpeed Read

-

North Korea fires 2 ballistic missiles into sea

North Korea fires 2 ballistic missiles into seaSpeed Read

-

U.S. airstrikes target Iranian-backed militia facilities in Syria

U.S. airstrikes target Iranian-backed militia facilities in SyriaSpeed Read

-

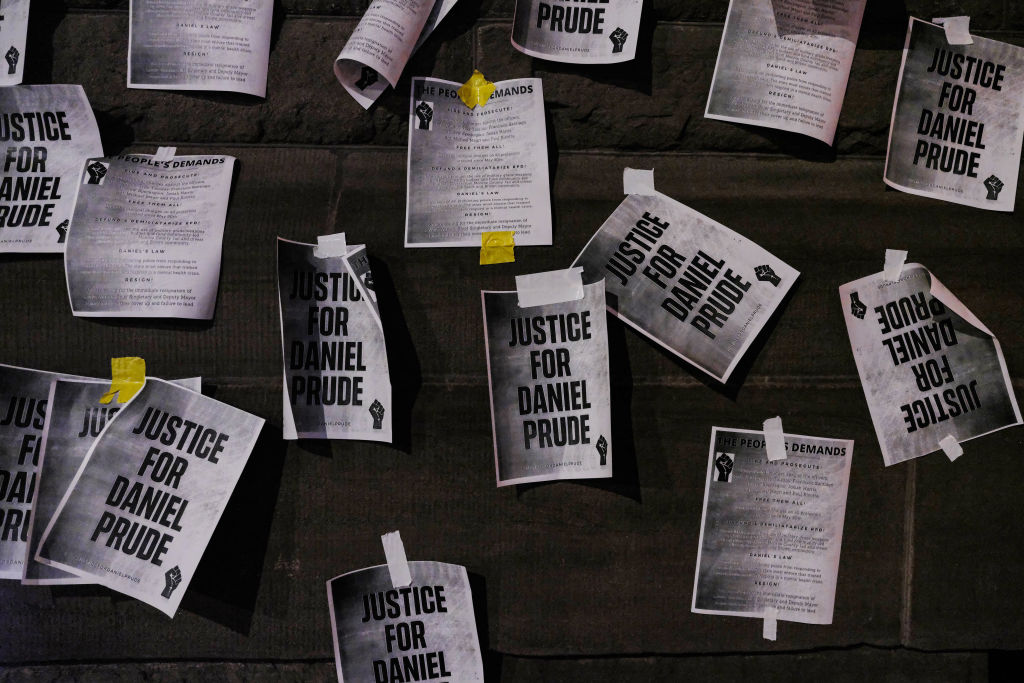

Rochester police who killed Daniel Prude during mental health crisis won't face charges

Rochester police who killed Daniel Prude during mental health crisis won't face chargesSpeed Read

-

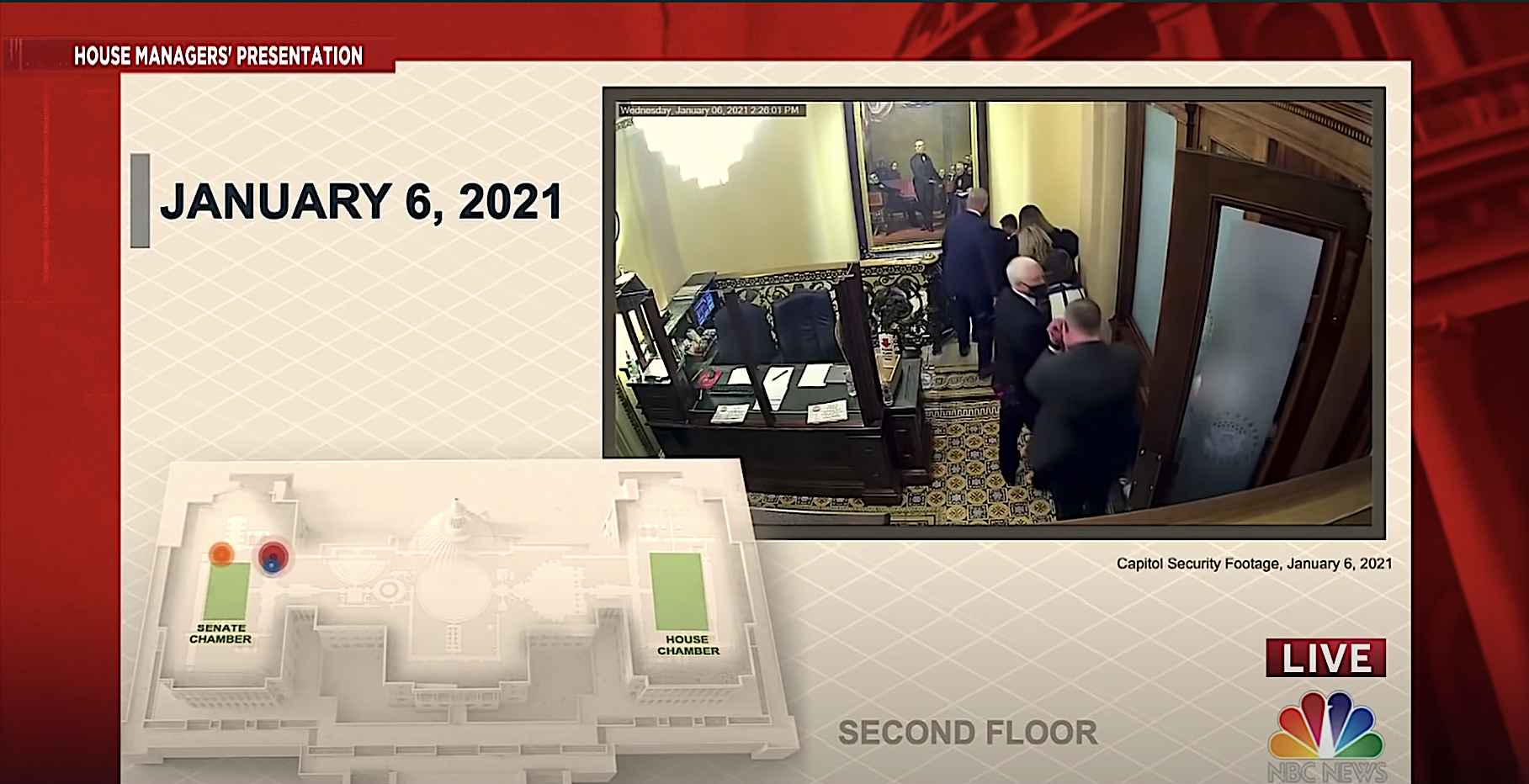

Mike Pence's 'nuclear football' was also apparently at risk during the Capitol siege

Mike Pence's 'nuclear football' was also apparently at risk during the Capitol siegeSpeed Read

-

Trump publicly attacked Pence during the Capitol riot knowing Pence was in trouble, GOP senator suggests

Trump publicly attacked Pence during the Capitol riot knowing Pence was in trouble, GOP senator suggestsSpeed Read