Life under the ISIS caliphate

Up to 8 million people in Syria and northern Iraq are living under the brutal rule of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria

Up to 8 million people in Syria and northern Iraq are living under the brutal rule of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria. Here's everything you need to know:

Is the Islamic State a state?

It doesn't operate as one, despite the grand declaration of a new "caliphate" last summer by its leader, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. In reality, its "state" in Syria and Iraq consists of several cities and many small towns and villages occupied by a large, brutal military force. On the battlefield, ISIS is quite competent, because it is led by a cadre of ex-Iraqi generals and veteran al Qaeda commanders with deep military training and experience. But its civilian administration of the territory it has conquered is primitive, with the population strictly controlled though draconian laws, barbaric punishments, and fear. Kirk Sowell, a Middle East analyst and risk consultant, says ISIS operates "like something between a mafia, an insurgency, and a terror group."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

How does it get money?

Any way it can. ISIS's grand ambitions, such as building its own currency, have yet to come about. People in its territory use Syrian pounds, Iraqi dinars, and U.S. dollars. ISIS's major challenge is paying and organizing its force of more than 30,000 fighters, operating across an area the size of Maryland. The group is said to make about $1 million a day through extortion, kidnapping, and selling crude oil from captured wells in Syria. It has also established some very basic bureaucracies and taxes: Trucks are charged 10 percent of their cargo's value when they enter ISIS-controlled regions; businesses pay 2.5 percent tax on their revenue each year. "If they don't take it," explains Mahmoud, a gas engineer in Syria, "they tax you for it."

What is daily life like?

ISIS is devoted to restoring the earliest, "purest" form of Islam, as practiced under the Prophet Mohammed and his followers in the 7th century. So in cities such as Raqqa, ISIS's de facto capital in northern Syria, and Mosul, in Iraq, "morality police" — called the Hisbah — patrol the streets, checking that shops are closed during prayers, men are bearded, and women are properly dressed. At checkpoints, the Hisbah inspect mobile phones for subversive text messages or Facebook entries, and ensure taxi drivers are listening to the official ISIS radio station. Former police officers, human rights activists — in fact, anyone deemed "heretical" — must carry a "repentance card” to show allegiance to ISIS. Dozens of "un-Islamic” activities — smoking, listening to music, wearing hair gel — are punishable by floggings, amputation, or execution. ISIS has released video footage of gay men being thrown off tall buildings to their deaths. Jews and Christians are given a choice to convert or die. Executions and floggings happen almost daily in streets and parks, sometimes with large crowds watching. One ISIS pamphlet from Aleppo lists punishments for crimes, including "Drinking alcohol: 80 lashes. Slander: 80 lashes. Spying in the service of infidels: death. Renunciation of Islam: death. Robbery: if robbery and murder are committed, death by crucifixion."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

What are the rules for women?

The severest, and most degrading, of all. Women in the Islamic State, an online manifesto written by female ISIS supporters, decrees that girls can marry at age 9, and should have husbands by 16 or 17. In certain ISIS-controlled regions, women must wear two black gowns to mask their body shape, and three veils so their eyes cannot be seen, even in sunlight. Any woman caught unaccompanied by a male relative, or breaching dress codes, is detained and flogged by the al-Khansaa Brigade, a pervasive all-female militia; those accused of adultery have been stoned to death. In Iraq, more than 1,300 women and children from the Yazidi community — a tiny religious minority — have been taken into sex slavery. A network of warehouses has been set up where the sex slaves, some as young as 12, are showcased like new cars, sold to ISIS fighters, and kept captive, The New York Times reported last week. "Every time that he came to rape me, he would pray," one 15-year-old girl said of the fighter who "owned" her. "He said that raping me was his prayer to God.”

How do people under its control feel about ISIS?

People brave enough to speak out against the group say it is feared and loathed. (See below). But for the mostly Sunni population in its territory, the depressing truth is that the alternatives — Bashar al-Assad's brutal Syrian regime, or Iraq's corrupt, Shiite-dominated regime — aren't much better. Indeed, in the early days of its victories in 2013 and 2014, Sunnis largely welcomed ISIS. That's changing, because living conditions are badly deteriorating. In some regions, gasoline costs as much as $18 a gallon. Prices of cooking gas, flour, bread, and other essentials have also soared; people are rationing water and burning wood amid shortages and power outages. "Maybe [ISIS] thought six months ago they were going to function as a state," says Sowell, "but they don't have the personnel or manpower." The critical question is whether any government in the chaotic region can do a better job.

Breaking the silence

Since ISIS poses a mortal threat to journalists — it has killed dozens of mostly local reporters, as well as its high-profile Western victims — the job of exposing the group's barbarity has fallen to civilians. In April 2014, a group of student activists set up Raqqa Is Being Slaughtered Silently inside the ISIS capital. Its two dozen or so members post written reports and videos — often filmed on mobile phones hidden in the sleeves of jackets — documenting daily life under ISIS control. One recent film showed the execution of a woman in the street for deceiving her husband; had the person who filmed it been caught, the punishment would have been death. One member of the group has been caught and killed. To avoid that fate, the contributors never meet in person, only on encrypted networks online. "We can't fight [ISIS] with weapons. We can only fight them with words," says founder Abu Mohammed. "To defeat us, they would have to shut down the internet."

-

Political cartoons for January 3

Political cartoons for January 3Cartoons Saturday's political cartoons include citizen journalists, self-reflective AI, and Donald Trump's transparency

-

Into the Woods: a ‘hypnotic’ production

Into the Woods: a ‘hypnotic’ productionThe Week Recommends Jordan Fein’s revival of the much-loved Stephen Sondheim musical is ‘sharp, propulsive and often very funny’

-

‘Let 2026 be a year of reckoning’

‘Let 2026 be a year of reckoning’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

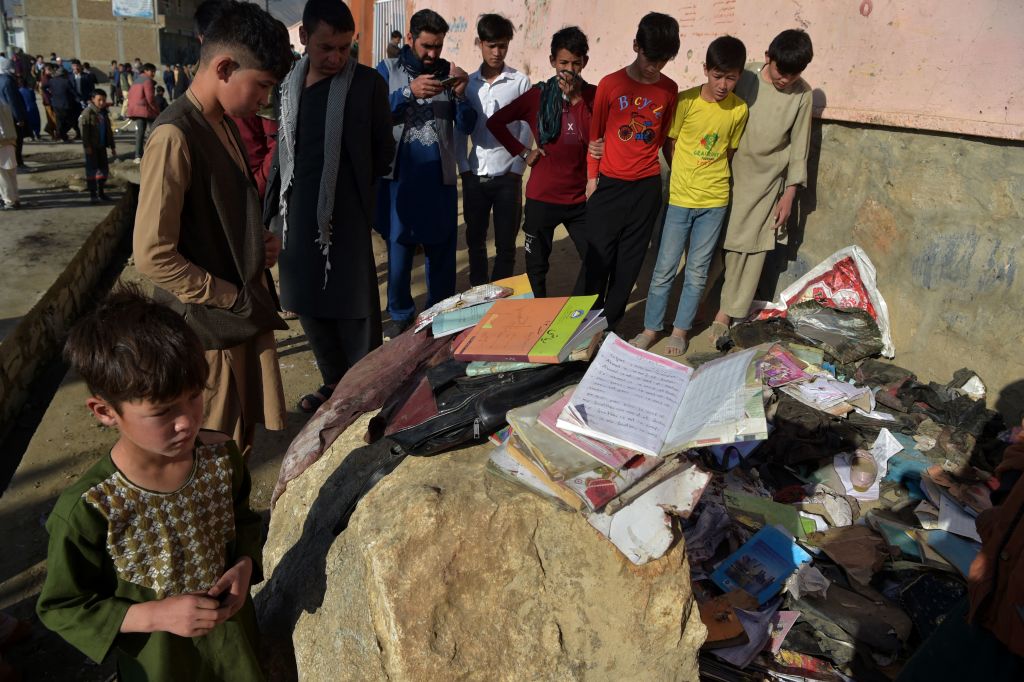

Bombing at girls' school in Kabul kills at least 50, including students

Bombing at girls' school in Kabul kills at least 50, including studentsSpeed Read

-

Garland says DOJ is 'pouring its resources' into stopping domestic terrorists 'before they can attack'

Garland says DOJ is 'pouring its resources' into stopping domestic terrorists 'before they can attack'Speed Read

-

Suspected Israeli cyberattack on Iranian nuclear site complicates U.S.-Iran nuclear deal talks

Suspected Israeli cyberattack on Iranian nuclear site complicates U.S.-Iran nuclear deal talksSpeed Read

-

North Korea fires 2 ballistic missiles into sea

North Korea fires 2 ballistic missiles into seaSpeed Read

-

U.S. airstrikes target Iranian-backed militia facilities in Syria

U.S. airstrikes target Iranian-backed militia facilities in SyriaSpeed Read

-

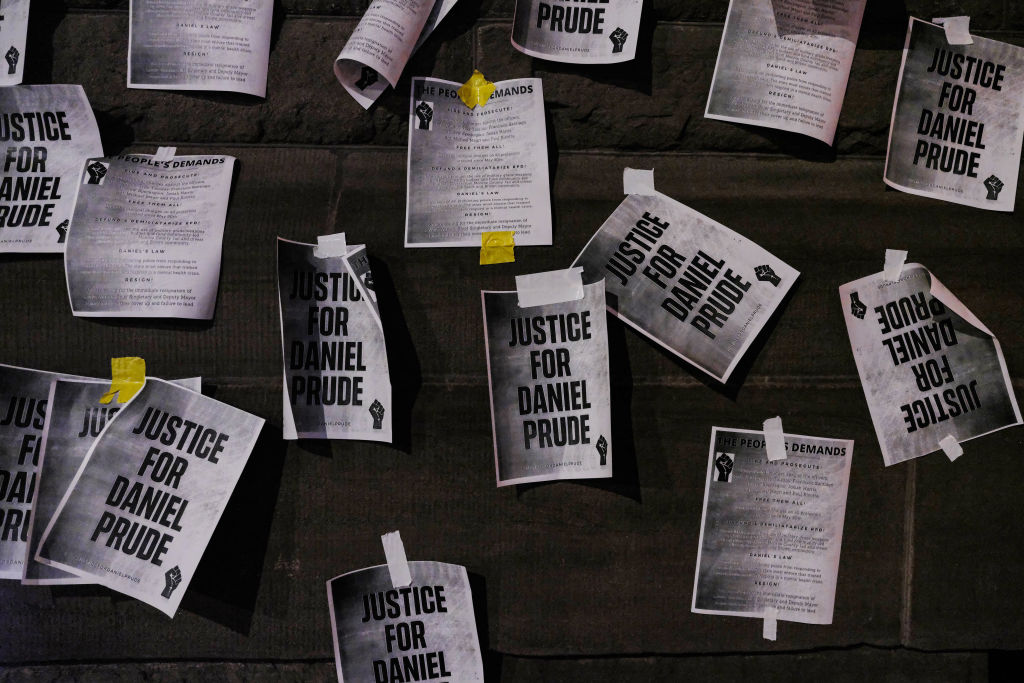

Rochester police who killed Daniel Prude during mental health crisis won't face charges

Rochester police who killed Daniel Prude during mental health crisis won't face chargesSpeed Read

-

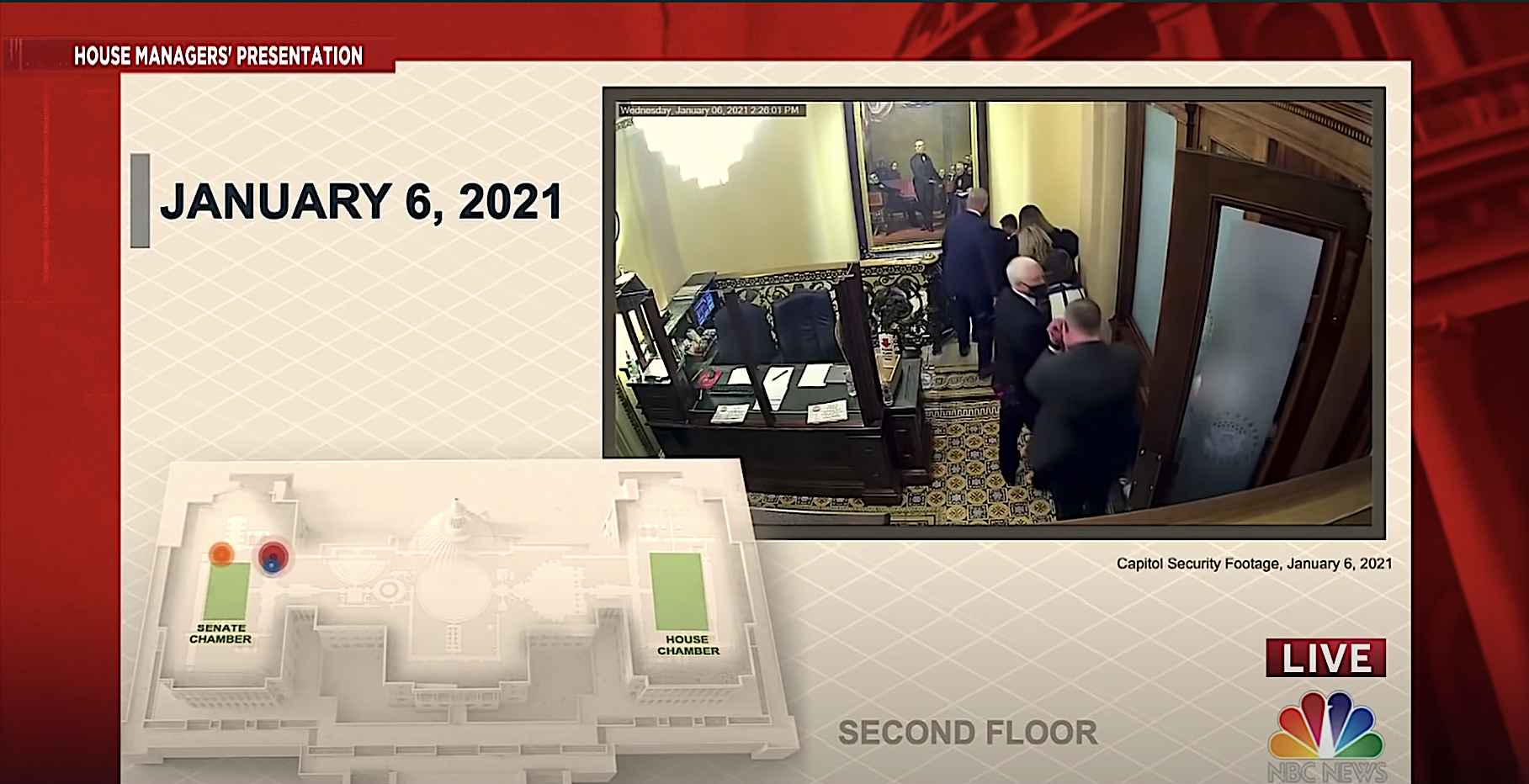

Mike Pence's 'nuclear football' was also apparently at risk during the Capitol siege

Mike Pence's 'nuclear football' was also apparently at risk during the Capitol siegeSpeed Read

-

Trump publicly attacked Pence during the Capitol riot knowing Pence was in trouble, GOP senator suggests

Trump publicly attacked Pence during the Capitol riot knowing Pence was in trouble, GOP senator suggestsSpeed Read