A brief guide to America's sharing economy

Millions of people are getting paid to share cars, homes, and services with people who need them. Is that all good?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Millions of people are getting paid to share cars, homes, and services with people who need them. Is that all good? Here's everything you need to know:

What is the sharing economy?

Coined in Silicon Valley, the term refers to "collaborative consumption" — the phenomenon of people sharing cars, apartments, power tools, and other underused assets with people willing to pay for them. Companies have sprung up to serve as matchmakers between sellers and buyers, most famously Uber, a car service that pairs riders with nearby drivers; Airbnb, which helps people rent out homes and apartments; and TaskRabbit, a web platform that outsources odd jobs to people in your neighborhood. These companies all take a cut of the transaction — Uber, for example, gets 30 percent of the driver's fee. The new arrangements give providers a flexible source of extra income and users quick access to cheaper goods and services, available 24/7 through apps on their smartphones. Five years ago, consumers were very skeptical about sharing services, says Rachel Botsman, author of What's Mine Is Yours, a book on the sharing economy. "[People were saying] 'I'm not going to trust a stranger with my car,' or 'How could you let just anyone into your home?'" That attitude, she says, has changed to "'I never realized how much money I could make or how much money I could save.'"

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

How did it all start?

With the advent of the internet and its limitless potential to connect people around the globe. One of the most significant groundbreakers was Napster, the music-sharing service that shut down in 2001 after a copyright infringement suit, but sparked a revolution in the way people consume music. Uber, launched in 2009, has exploded into a $40 billion worldwide company, and its chief competitor, Lyft, now operates in about 65 U.S. cities. Airbnb founder Brian Chesky started out by renting three air mattresses; now his web service features listings in 190 countries, offering up space in everything from tree houses to castles. Online marketplaces, such as Vinted and Poshmark, allow people to sell or swap unwanted clothes and accessories; DogVaycay lets you board your pet in a loving home instead of a kennel. A survey last year found that 18 percent of Americans have been consumers in the sharing economy, and of those, 83 percent say it "makes life more convenient and efficient."

Is everyone enthusiastic?

No. As the sharing economy booms, it's experiencing major growing pains. When it began, the peer-to-peer model had an idealistic, egalitarian aura. But critics have begun to see a darker side to the sharing economy, and some call the term itself a misnomer. "Actually, it's anti-sharing, because they are commodifying resources that before would have been shared for free, like, if you had a spare room in your house you would invite some friends," says Michel Bauwens, founder of the P2P Foundation, a research group on peer-to-peer interactions. In some cities, people have even tried to make money by taking up multiple parking spaces on public streets and auctioning them off via apps. (Cities have cracked down on these services.) Turning everything into a commodity to be sold "doesn't sound like the sharing economy," says Brooklyn Law School professor Jonathan Askin. "It sounds like the selfish economy." Government regulators have also charged that some of these startups endanger the public.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Why is government concerned?

Sharing startups often operate under the radar, evading consumer protection laws and regulations. In the case of Airbnb, regulators say that many of its listings aren't by individual homeowners and renters but by professional landlords taking advantage of higher day rates — essentially running de facto hotels, prohibited in many municipalities. Escort services, meanwhile, have been known to rent out Airbnb apartments to conduct business. "It's more discreet and much cheaper than the Waldorf," one New York City sex worker explained. In several cities, Uber and Lyft drivers have been accused of sexually assaulting passengers, and last week Los Angeles and San Francisco prosecutors charged that Uber had failed to screen out 25 drivers with criminal records who'd given thousands of rides. New business models do not "give companies a license to mislead consumers about issues affecting their safety," said San Francisco District Attorney George Gascón.

What about the new jobs created?

The sharing economy is also called the "gig" economy, because it involves on-demand freelance work, without the benefits — health care, paid vacation, sick leave, and a retirement plan — and workplace protections associated with a steady job. Most sharing-economy companies insist they're not employers, but middlemen facilitating transactions between individuals. For-mer U.S. Labor Secretary Robert Reich finds that argument disingenuous. "The big money goes to the corporations that own the software," he says. "The scraps go to the on-demand workers." But Simon Rothman, of the venture capital firm Greylock Partners, argues that sharing-economy jobs are ideal for what he calls "uncollared workers," enabling them to "work when they want to work, and do the job that they want to do." That arrangement isn't for everyone, but for those who don't want full-time jobs, he says, it's a great option.

The Uber wars

If Uber is the face of the sharing economy, it's taken a lot of blows to the chin. In New York City, Mayor Bill de Blasio tried unsuccessfully to limit the number of Uber cars, claiming they were jamming already overcrowded streets. Plaintiffs in Texas have filed suits claiming the company and its competitor Lyft are violating the Americans With Disabilities Act, by failing to accommodate wheelchair users. And in June, the California Labor Commission ruled in favor of Barbara Ann Berwick, a San Francisco Uber driver who sued for $4,152 in expenses, claiming she was an employee, not an independent contractor. Uber has appealed, maintaining its drivers embrace their independence. "The No. 1 reason drivers choose to use Uber," a spokeswoman said, "is because they have complete flexibility and control." But as "sharing economy" companies grow large, the way Uber has, they begin to seem like conventional businesses. And that's when they attract unwanted attention from lawyers and government regulators.

-

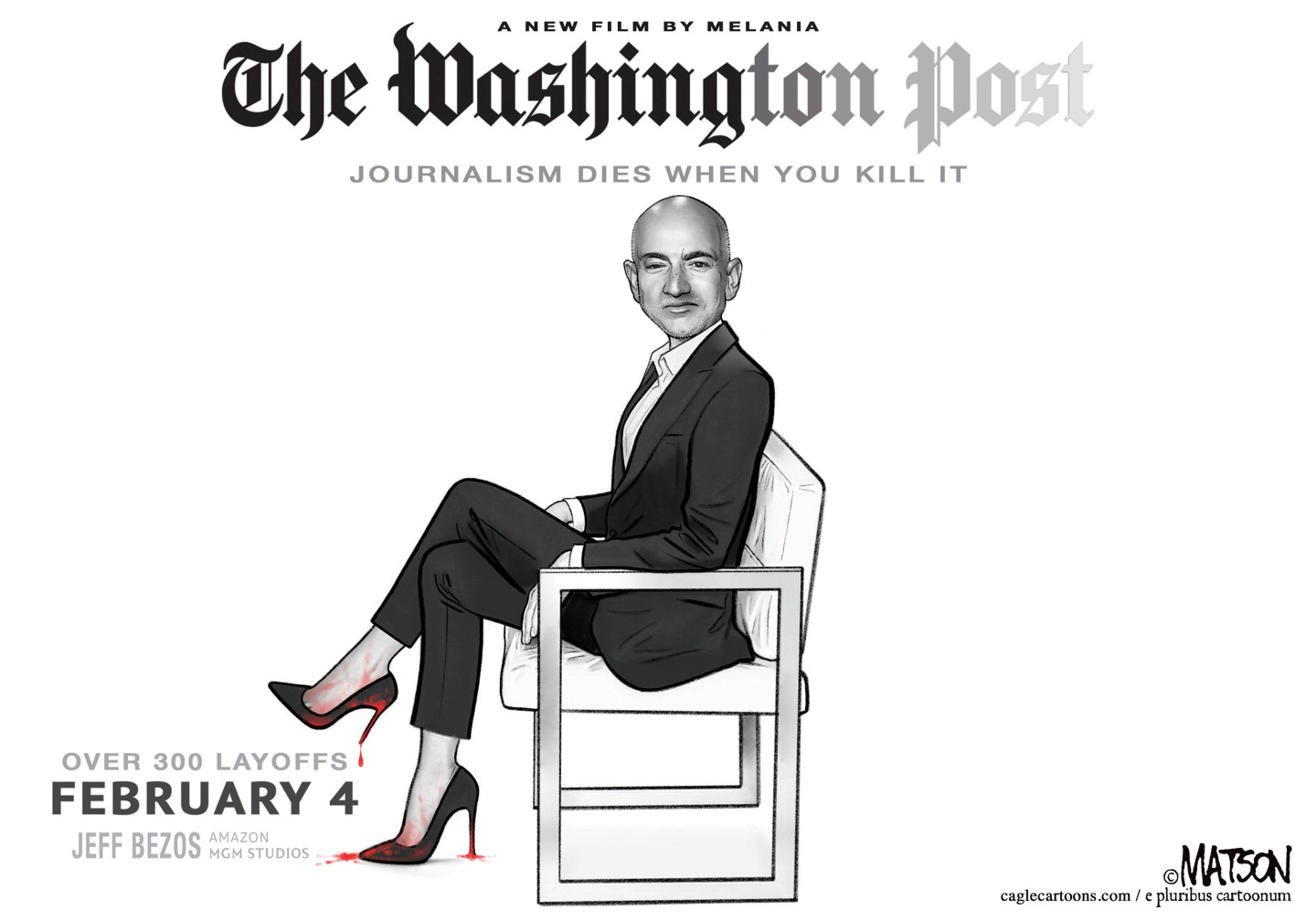

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'Cartoons Artists take on a girlboss, a fetching newspaper, and more

-

The fall of the generals: China’s military purge

The fall of the generals: China’s military purgeIn the Spotlight Xi Jinping’s extraordinary removal of senior general proves that no-one is safe from anti-corruption drive that has investigated millions

-

Why the Gorton and Denton by-election is a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’

Why the Gorton and Denton by-election is a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’Talking Point Reform and the Greens have the Labour seat in their sights, but the constituency’s complex demographics make messaging tricky

-

The pros and cons of noncompete agreements

The pros and cons of noncompete agreementsThe Explainer The FTC wants to ban companies from binding their employees with noncompete agreements. Who would this benefit, and who would it hurt?

-

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contraction

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contractionThe Explainer The sharpest opinions on the debate from around the web

-

The death of cities was greatly exaggerated

The death of cities was greatly exaggeratedThe Explainer Why the pandemic predictions about urban flight were wrong

-

The housing crisis is here

The housing crisis is hereThe Explainer As the pandemic takes its toll, renters face eviction even as buyers are bidding higher

-

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkers

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkersThe Explainer Show up for your colleagues by showing that you see them and their struggles

-

What the stock market knows

What the stock market knowsThe Explainer Publicly traded companies are going to wallop small businesses

-

Can the government save small businesses?

Can the government save small businesses?The Explainer Many are fighting for a fair share of the coronavirus rescue package

-

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shock

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shockThe Explainer This could be a huge problem for the entire economy