Here's the real problem with Jeremy Corbyn's wacky money-printing scheme

It's not radical enough!

Jeremy Corbyn, the new leader of the Labour Party in the U.K., has an economic policy idea that is far outside the realm of traditional discussion. He calls it "people's quantitative easing," and basically it involves paying for new infrastructure projects with printed money.

This isn't a terrible idea.

At the least it would be dramatically more effective than the existing QE regime. However, the "people's" part of the label is to a large degree sloganeering, and Corbyn's plan would be even better if he made it an accurate one. Print the money, and give it straight to the people!

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But first, let's review the idea behind quantitative easing. Traditionally, central banks stimulate the economy by lowering short-term interest rates. But they can't go past zero percent (or at least, not very far below it), so if they go all the way to the bottom and the economy is still depressed, as happened across most of the industrialized world in 2008-9, central bankers have to come up with new tools. QE is one of those. Basically, the central bank prints up some money and buys financial assets like long-term treasury bonds, with the idea of pushing down longer-term interest rates and thus sparking more lending and economic activity.

This has been better than nothing, but not very much better. In America, the Federal Reserve has created over $3 trillion in new money since the crisis, but by and large, it has not made it out into the broader economy. Instead it piled up in bank vaults as excess reserves. This is reflected in the general failure of central banks to meet their inflation targets (in the U.K., the U.S., and the eurozone), particularly recently — a symptom of insufficient spending throughout the economy.

Corbyn's QE, by contrast, entails funding infrastructure projects with newly printed money. This has the advantage that the money would definitely make it out into the broader economy, and also in that it would allow for government projects to be funded without taxes whenever a recession happened. Remember, economic weakness presents a free lunch — perfectly good workers who are sitting around doing nothing, while factories and business sit idle or below capacity. As Paul Krugman says, "printing money can solve one specific problem, an economy operating far below capacity."

Corbyn's plan has a big disadvantage, however: There's no reason to think that infrastructure needs will match particularly well with economic downturns. Big projects usually take at least a year to plan, approve, and get started, while recessions can gather to full force over a few months. In an ideal world, infrastructure would be planned according to the needs of the population for infrastructure, not to deal with macroeconomic problems.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Of course, a country that is suffering economic slack would be insane not to upgrade whatever infrastructure that happens to need work (water systems come to mind); it just isn't an ideal mechanism for dealing with recessions in general.

That brings me to a real people's QE, also known as helicopter money. Under such a program, the central bank would be empowered to send out equal checks to all individual citizens according to their estimation of how strong or weak the economy is. During boom times, the checks would be tiny, but during recessions, they would be fairly large. The idea is to juice the economy with money until a bit of inflation is seen — thus signaling that capacity had been reached — and back off the payments, with traditional interest rate tools available to control price increases if necessary.

People's QE has the advantage of being even more likely to be spent than infrastructure dollars, and able to be scaled up almost instantaneously. It's also much fairer — recessions are a systemic problem, and a per-capita distribution of equal payments spreads money through throughout the entire population.

It would be a massive upgrade to current central bank practice. During the so-called Great Moderation from about 1983-2007, the operative unit of monetary policy was credit. This had a marked tendency to induce borrowing on the part of citizens, which leads to debt overhangs. No such worry with people's QE.

It would also work faster. Unlike current monetary policy, which famously works with "long and variable lags," people's QE could be cranked up and back extremely quickly. Hence, no need to tighten policy before one even sees inflation, meaning you bypass the risk of strangling a potential low-inflation boom in the cradle.

Most importantly, this would be a tool that could last indefinitely. There is good reason to think that the low interest rate, low inflation status quo could persist for a very long time. The Bank of England would be armed against not just this depression, but all future ones as well.

I get the sense that what inspires Corbyn's proposal is the fact that of all the new money created during QE, most of the benefit has gone to the rich through asset price increases. That is legitimately infuriating, and so people think of useful things new money could buy that don't involve juicing the stock market. But he really ought to aim higher. Real people's QE is a tool that would make the terrifying economic sandpit of the zero lower bound — where Japan has been mired for decades now — a thing of the past, forever.

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.

-

High Court action over Cape Verde tourist deaths

High Court action over Cape Verde tourist deathsThe Explainer Holidaymakers sue TUI after gastric illness outbreaks linked to six British deaths

-

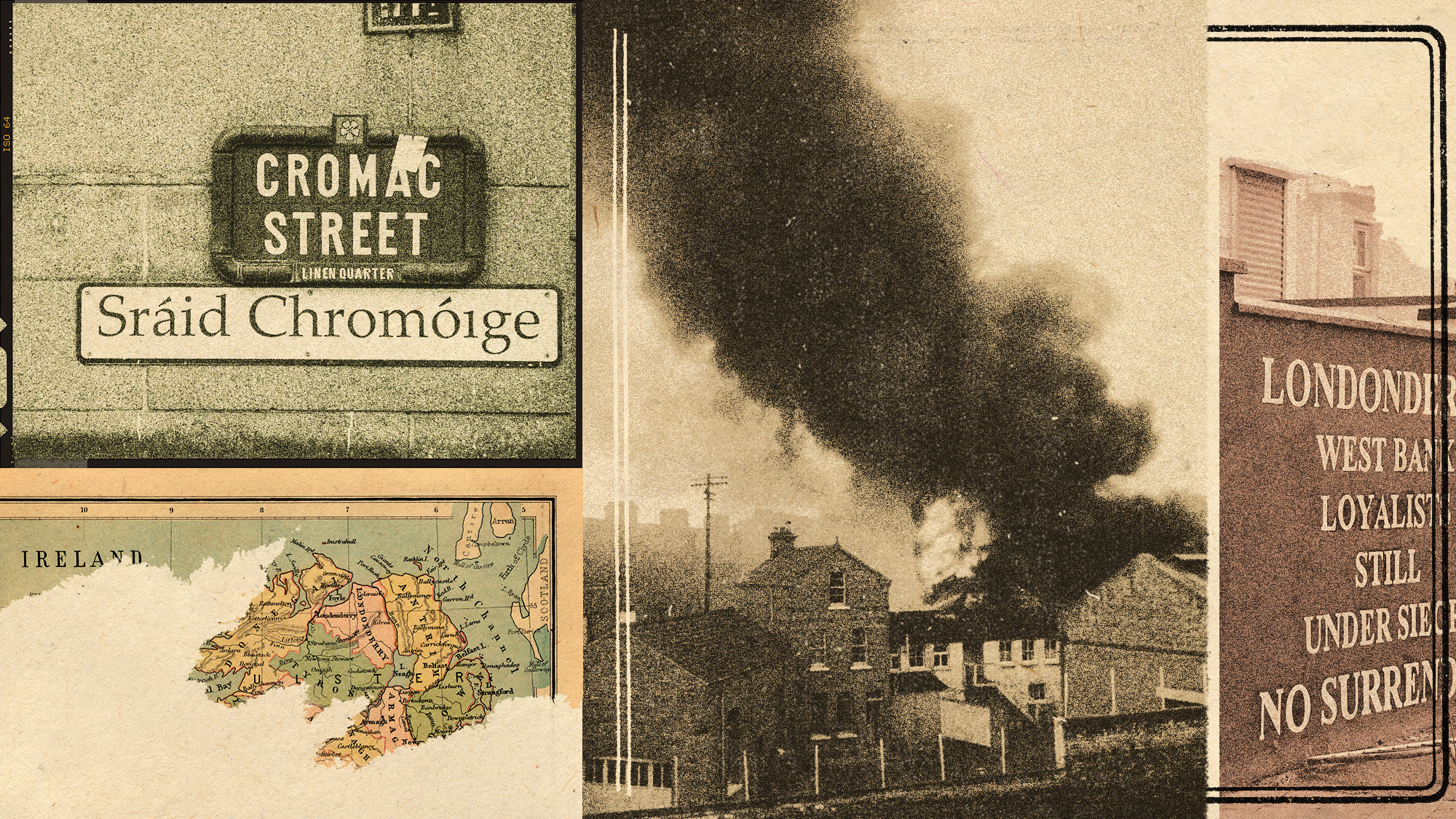

The battle over the Irish language in Northern Ireland

The battle over the Irish language in Northern IrelandUnder the Radar Popularity is soaring across Northern Ireland, but dual-language sign policies agitate division as unionists accuse nationalists of cultural erosion

-

Villa Treville Positano: a glamorous sanctuary on the Amalfi Coast

Villa Treville Positano: a glamorous sanctuary on the Amalfi CoastThe Week Recommends Franco Zeffirelli’s former private estate is now one of Italy’s most exclusive hotels