Dylann Roof, Joey Meek, and the scourge of white poverty

Why didn't Dylann Roof's friends turn him in? The answer may be staring us in the face.

The alleged mass murderer Dylann Roof had some friends, did you know? One of them, Joey Meek, was recently arrested by federal authorities, for allegedly hearing about the planned massacre in Charleston, South Carolina, and failing to turn Roof in to the cops.

This was all prefigured by a longform piece in The Washington Post about Roof's friends, entitled "An American Void," by Stephanie McCrummen. It told the story of Meek, a 21-year-old man who lives with his mother, girlfriend, and two younger brothers in a trailer in Red Bank, South Carolina.

It's an interesting article as much for what it leaves out as what it contains. There is no mention of poverty, a serious and underappreciated problem among white Americans.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

A lot of other journalists praised McCrummen's piece, but I found it disorganized and frankly rather condescending. For a piece ostensibly investigating how people could be friends with a deranged racist and not call the police after hearing about a planned mass murder, it was a lot more concerned with expressing horrified disgust about the Meeks' lifestyle rather than figuring them out.

"[T]his is the place [Roof] drifted into with little resistance, an American void where little is sacred and little is profane and the dominant reaction to life is what Joey does now, looking at Lindsey. He shrugs," writes McCrummen. "What kind of people would do nothing?"

There seem to be five main characteristics of such people, according to McCrummen's account. The Meeks 1) play a lot of violent video games; 2) chain-smoke cigarettes; 3) drink to excess; 4) live in a trailer; and 5) scroll constantly on their cellphones. The piece hangs an absurd amount of weight on the first item, mentioning it as early as the second paragraph and a dozen times more throughout the text, with lurid descriptions of the virtual violence. "One or more of the Meek brothers and their friends are playing the Xbox almost constantly," says a picture caption. It should be noted that long-term studies have found no connection between games and acts of violence.

The looming reality here, which goes almost totally unmentioned by McCrummen, is poverty. Though both Joey and his mother work, it seems pretty clear that the family is quite poor.

I have no idea whether McCrummen knows lots of poor white people, but the facts of her story are quite familiar to me. A good number of my high school friends would have fit right in with the Meek household — hard-drinking chain-smokers living in dilapidated trailers so old you had to get fuses on special order since they didn't sell them at the hardware store anymore.

It turns out that rural white poverty is not so different from any other kind. It tends to narrow social horizons to immediate friends and family, if not further. With few other sources of emotional support, self-medication via cigarettes, alcohol, or more is common. The escapism of video games is enormously attractive, and why not? Where else can one get an appealing, cheap simulacrum of an exciting lifestyle where success is obtained by following easily understood rules?

Poverty is also associated with violence, and the Meeks are no exception. One of their friends killed himself with a shotgun. Another time, a man stopped by with a pistol looking to confront another of the Meeks' friends, but Joey faced him down. Both incidents clearly scarred the whole family.

It's not remotely surprising to me that such people, already battered to the emotional breaking point, would instinctively disbelieve awful things a friend said, and refuse to consider turning him in to the police. For poor people, the cops are the cold, brutal machine that might nail you on that truck registration you didn't have the money to pay for last month, or put your little brother in foster care, or turn you over to private probation companies to be held for ransom, or simply beat the hell out of you for no reason.

As Michael Harrington once wrote:

For the middle class, the police protect property, give directions, and help old ladies. For the urban poor, the police are those who arrest you. In almost any slum there is a vast conspiracy against the forces of law and order. If someone approaches asking for a person, no one there will have heard of him, even if he lives next door. [The Other America]

That raises several questions that McCrummen leaves unanswered: Where does Joey work? How much does he make? (She mentions him coming home from a 14-hour day at work, but nothing more.) What does he think of Roof's white supremacist argle-bargle? What's the story with the black neighbor, who apparently hangs out at the trailer sometimes? She doesn't tell us.

That's not to say that Joey Meek isn't in the wrong; maybe he is. But here are some facts: As of 2013, 42 percent of all poor people were white (as compared to 23 percent black and 28 percent Hispanic). Their lives are generally better than poor blacks' are, but not by much. Poor white life expectancy has fallen by four years since 1990. Among the cohort of men born between 1975 and 1979, poor whites are at the second-greatest lifetime risk of incarceration (behind poor blacks).

Video games, smoking, and excessive cellphone use are not remotely as plausible as simple poverty in explaining the Meeks' failure to turn in Roof. Constantly getting the worst out of life tends to grind a person into a state of passive acceptance.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

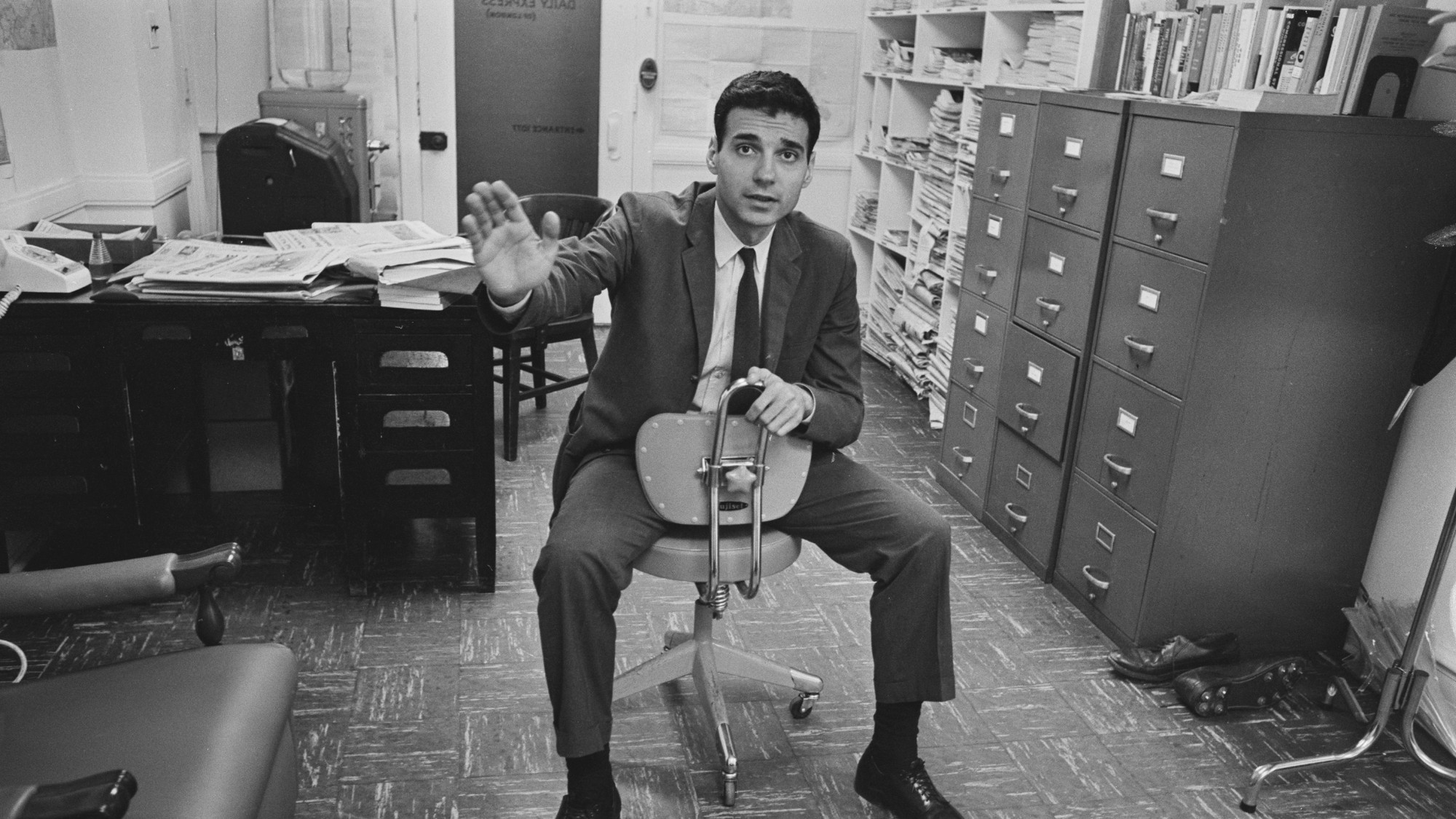

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.

-

'We need solutions that prioritize both safety and sustainability'

'We need solutions that prioritize both safety and sustainability'Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Book reviews: 'Moral Ambition: Stop Wasting Your Talent and Start Making a Difference' and 'Is a River Alive?'

Book reviews: 'Moral Ambition: Stop Wasting Your Talent and Start Making a Difference' and 'Is a River Alive?'Feature A rallying cry for 'moral ambition' and the interwoven relationship between humans and rivers

-

'King of the Hill' actor shot dead outside home

'King of the Hill' actor shot dead outside homespeed read Jonathan Joss was fatally shot by a neighbor who was 'yelling violent homophobic slurs,' says his husband