Book reviews: 'Moral Ambition: Stop Wasting Your Talent and Start Making a Difference' and 'Is a River Alive?'

A rallying cry for 'moral ambition' and the interwoven relationship between humans and rivers

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

'Moral Ambition: Stop Wasting Your Talent and Start Making a Difference' by Rutger Bregman

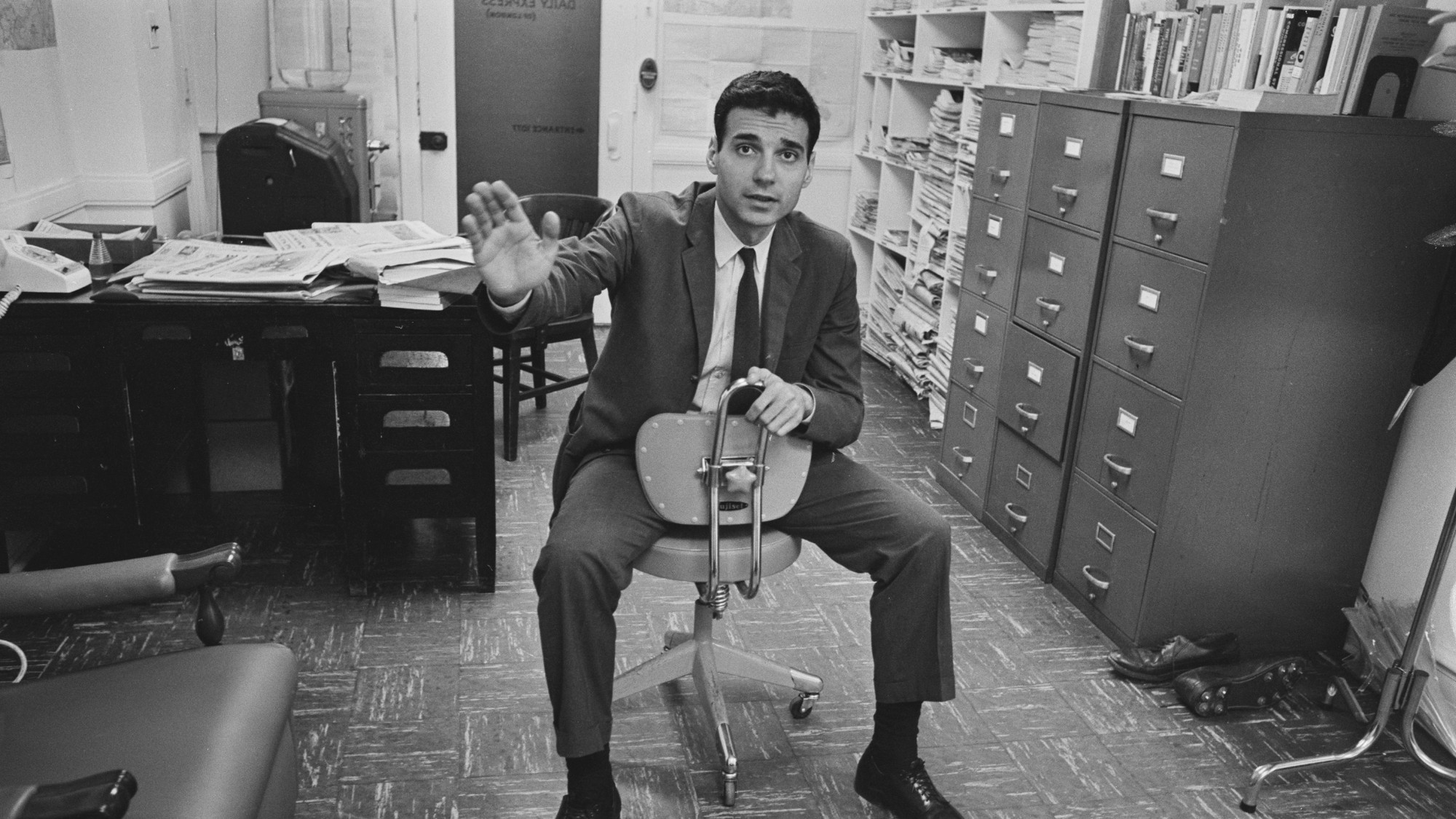

Rutger Bregman's latest book "makes profound change look easy," said Isabel Berwick in Financial Times. The Dutch author of the best-seller Humankind: A Hopeful History has set his sights on today's educated elite, urging each of his readers to reject the allure of high-paying but damaging or pointless careers and choose instead to devote their careers to doing good for the world. While the suggestion may sound unrealistic, "there's a playbook here," as Bregman shares stories about the successes achieved when individual idealists have banded together in teams, such as the army of young lawyers Ralph Nader assembled in the 1960s and '70s to rewrite U.S. environmental and consumer protection law. The great challenges of our own time are many, and Bregman's "brisk and persuasive" argument stands a chance of waking many readers to the role they can play in meeting them.

His opening idea "may sound like a promising point of departure," said Helmer Stoel in Jacobin. He puts people into four categories: those who are neither idealistic nor ambitious, those who are ambitious but unidealistic, those who are idealistic but unambitious, and those who get the mix right. Sure, few of us want to fall into any of the first three categories. The first group, in his moral cosmos, winds up in "bullshit jobs," and he dismisses the sorry third cohort as "noble losers." But Bregman is so focused on coaching readers how to find individual satisfaction that he makes the heroic individual efforts to do good more important than the righteousness of any collective cause. "It is not clear what the 'good' is that needs doing."

Still, "the stories that Bregman tells are vivid and often genuinely inspiring," said Rowan Williams in The Guardian. He writes of a young Cambridge University graduate deciding in 1785 at age 24 to commit his life to ending slavery worldwide—and largely succeeding. He writes about Dutch and French families who sheltered their Jewish neighbors during the Nazi occupation, and of the strategic thinking that made the 1955 Montgomery, Ala., bus boycott so effective. Beyond all that, he also acknowledges his heroes' errors, such as when a messianic streak led Nader to stay in the 2000 presidential election even though that choice put a free-market Republican in the White House. Should you remain skeptical, maybe Bregman will turn you around at the end of the book, when he argues that doubting that an individual can make a difference is essentially egotistical because doing so rejects how interwoven one's actions are with those of all other humans. "Oversimplified? Perhaps. But calls to arms often have to be."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

'Is a River Alive?' by Robert Macfarlane

"Robert Macfarlane is the most engaging of British writers," said Pico Iyer in Air Mail. The 48-year-old nature writer and Cambridge University professor produces prose "as dense as a forest but flooded with sunlight." And "savingly," he also has a sense of humor. In his new book, the tireless explorer shares his journeys to three threatened river systems—in the cloud forests of Ecuador, in southernmost India, and in northeastern Canada—each time cataloging what the rivers give to humans and what humans give back. Despite all the damage he sees, he "tenaciously assembles a history, and a geography, of hope," showing that the ancient idea of rivers as living entities is again taking hold, changing law and politics in countries scattered across the globe.

Macfarlane decides to refer to each river as a "who," not an "it," and that's "jarring at first," said Clea Simon in The Boston Globe. But you adjust to it, helped by the many quoted Indigenous sources who do the same. The book proves to be "a compelling, if occasionally maddening, read, veering from gorgeous, almost hallucinatory writing into overeffusiveness." Still, as Macfarlane weaves in the stories of activists and the beliefs of far-flung river cultures, he succeeds in "building a foundation for his case that is both deep and broad." And as dense as the book can be, it is also "a profoundly beautiful and moving work."

Alas, "the sentimentality of the writing reflects a certain sentimentality of thought," said Becca Rothfeld in The Washington Post. Macfarlane never tells us what he means by calling a river a living thing. "Surely not everything dynamic is alive," and "just as surely, something does not need to be alive to be worthy of reverence." To insist on calling a river alive is to cram it into a human category when "it is the very strangeness of rivers and mountains and other inanimate solidities that moves and compels us." But the book's mission isn't to win a logical argument, said Mark Dery in 4Columns. "Running like a cross-current beneath Macfarlane's passionate, activist storytelling is a bracingly new approach to nature writing." Urging us to unplug from rationalism and embrace animism, "he dreams of nothing less than the re-enchantment of the world."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

Wuthering Heights: ‘wildly fun’ reinvention of the classic novel lacks depth

Wuthering Heights: ‘wildly fun’ reinvention of the classic novel lacks depthTalking Point Emerald Fennell splits the critics with her sizzling spin on Emily Brontë’s gothic tale

-

Why the Bangladesh election is one to watch

Why the Bangladesh election is one to watchThe Explainer Opposition party has claimed the void left by Sheikh Hasina’s Awami League but Islamist party could yet have a say

-

The world’s most romantic hotels

The world’s most romantic hotelsThe Week Recommends Treetop hideaways, secluded villas and a woodland cabin – perfect settings for Valentine’s Day

-

6 gorgeous homes in warm climes

6 gorgeous homes in warm climesFeature Featuring a Spanish Revival in Tucson and Richard Neutra-designed modernist home in Los Angeles

-

Touring the vineyards of southern Bolivia

Touring the vineyards of southern BoliviaThe Week Recommends Strongly reminiscent of Andalusia, these vineyards cut deep into the country’s southwest

-

Nan Goldin: The Ballad of Sexual Dependency – an ‘engrossing’ exhibition

Nan Goldin: The Ballad of Sexual Dependency – an ‘engrossing’ exhibitionThe Week Recommends All 126 images from the American photographer’s ‘influential’ photobook have come to the UK for the first time

-

American Psycho: a ‘hypnotic’ adaptation of the Bret Easton Ellis classic

American Psycho: a ‘hypnotic’ adaptation of the Bret Easton Ellis classicThe Week Recommends Rupert Goold’s musical has ‘demonic razzle dazzle’ in spades

-

Properties of the week: houses near spectacular coastal walks

Properties of the week: houses near spectacular coastal walksThe Week Recommends Featuring homes in Cornwall, Devon and Northumberland

-

Melania: an ‘ice-cold’ documentary

Melania: an ‘ice-cold’ documentaryTalking Point The film has played to largely empty cinemas, but it does have one fan

-

Nouvelle Vague: ‘a film of great passion’

Nouvelle Vague: ‘a film of great passion’The Week Recommends Richard Linklater’s homage to the French New Wave

-

Wonder Man: a ‘rare morsel of actual substance’ in the Marvel Universe

Wonder Man: a ‘rare morsel of actual substance’ in the Marvel UniverseThe Week Recommends A Marvel series that hasn’t much to do with superheroes