Does heroin really kill? A look at the science of overdoses.

If we're going to craft an effective drug policy, we need to set the record straight

Every time there's an airplane crash, somebody inevitably points out that driving a car is far more dangerous. Though death rates have fallen steadily in recent years, more than 30,000 people still died in motor vehicle accidents in 2013. That fact is by now a commonplace.

What is less well-known is that deaths from drug overdoses now far exceed that of car accidents. More than 46,000 people were killed by drugs in 2013. Most of these deaths were caused by prescription drugs, but for an increasing proportion heroin was the culprit — 8,200, to be exact. Most of these heroin deaths are chalked up to overdose in the media, but there are reasons to be suspicious of this characterization. Is it really simple overdose killing people?

For the most part, no. It turns out that most heroin deaths are probably not simple overdoses, but polydrug interactions, particularly between heroin and other nervous system depressants like benzodiazapines, tricyclic antidepressants, or alcohol. It's an important distinction both for addicts themselves and for crafting a drug policy focused on harm reduction.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What do we mean by overdose? This is when a drug user takes more than he or she can tolerate, and dies as a result. Heroin depresses the nervous system, so if you take too much, then you'll stop breathing and die. Simple.

The trouble with this story is that it is actually rather hard to overdose on simple heroin, particularly for experienced users. In fact, addicts are known to be capable of tolerating staggering quantities of pure heroin, dozens of times the average street dose in some experiments. It also usually takes several hours to die of a pure overdose, and treatment (with an opioid antagonist) is extremely simple — meaning that it ought to be pretty easy to save someone who has taken too much.

And complicating factors, the typical "overdose" fatality is typically not a naive heroin user — it's an older, long-term addict. (Though addicts who relapse after a period of sobriety — thus having lost their tolerance — are a significant minority.)

So if addicts are pretty resistant to overdoses, and the average heroin death is an experienced user, what gives? It turns out the answer is interactions with other drugs. Mixing heroin with other depressants is probably the most dangerous, because the effects do not combine linearly — instead, they reinforce and multiply each other. A small dose of heroin plus one beer may act as if they were a very large dose, plus a pint of vodka. A 2006 study found that roughly half of heroin deaths were also associated with alcohol.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

This effect holds for all similar drugs — witness Heath Ledger, who was killed by a mixture of prescription opioids, benzodiazapines, and an anti-insomnia drug. As addiction scientists Shane Darke and Michael Farrell write:

What does kill heroin users is polydrug use. More specifically, the use of heroin with other central nervous system depressants, such as alcohol and the benzodiazepines. Death is due to respiratory depression, from the combined effects of these substances. While one of these may not kill if taken alone, together they are toxic. That’s why we see a large number of deaths with low morphine concentrations. [LiveScience]

However, mixing heroin with stimulants is also dangerous. Heroin and cocaine, for example (the infamous "speedball"), also strengthen each other's effects, risking an overdose. Worse, cocaine wears off much faster than heroin, so one can have a heroin overdose on board, and not realize it until the cocaine starts fading out — at which point it's often too late. Doubling up on both is even riskier — witness Philip Seymour Hoffman, killed by two different stimulants and two different depressants at the same time.

All this matters for some kind of sensible drug policy focused on harm reduction. In order for addicts to get clean and shape up their lives, they obviously need to not be killed by drug cocktails. Heroin by itself is a risky business, but the most immediate danger is in mixing it with other drugs.

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.

-

San Francisco tackles affordability problems with free child care

San Francisco tackles affordability problems with free child careThe Explainer The free child care will be offered to thousands of families in the city

-

How realistic is the Democratic plan to retake the Senate this year?

How realistic is the Democratic plan to retake the Senate this year?TODAY’S BIG QUESTION Schumer is growing bullish on his party’s odds in November — is it typical partisan optimism, or something more?

-

Taxes: It’s California vs. the billionaires

Taxes: It’s California vs. the billionairesFeature Larry Page and Peter Thiel may take their wealth elsewhere

-

Democrats plan to make every House Republican take a vote on GOP Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene

Democrats plan to make every House Republican take a vote on GOP Rep. Marjorie Taylor GreeneSpeed Read

-

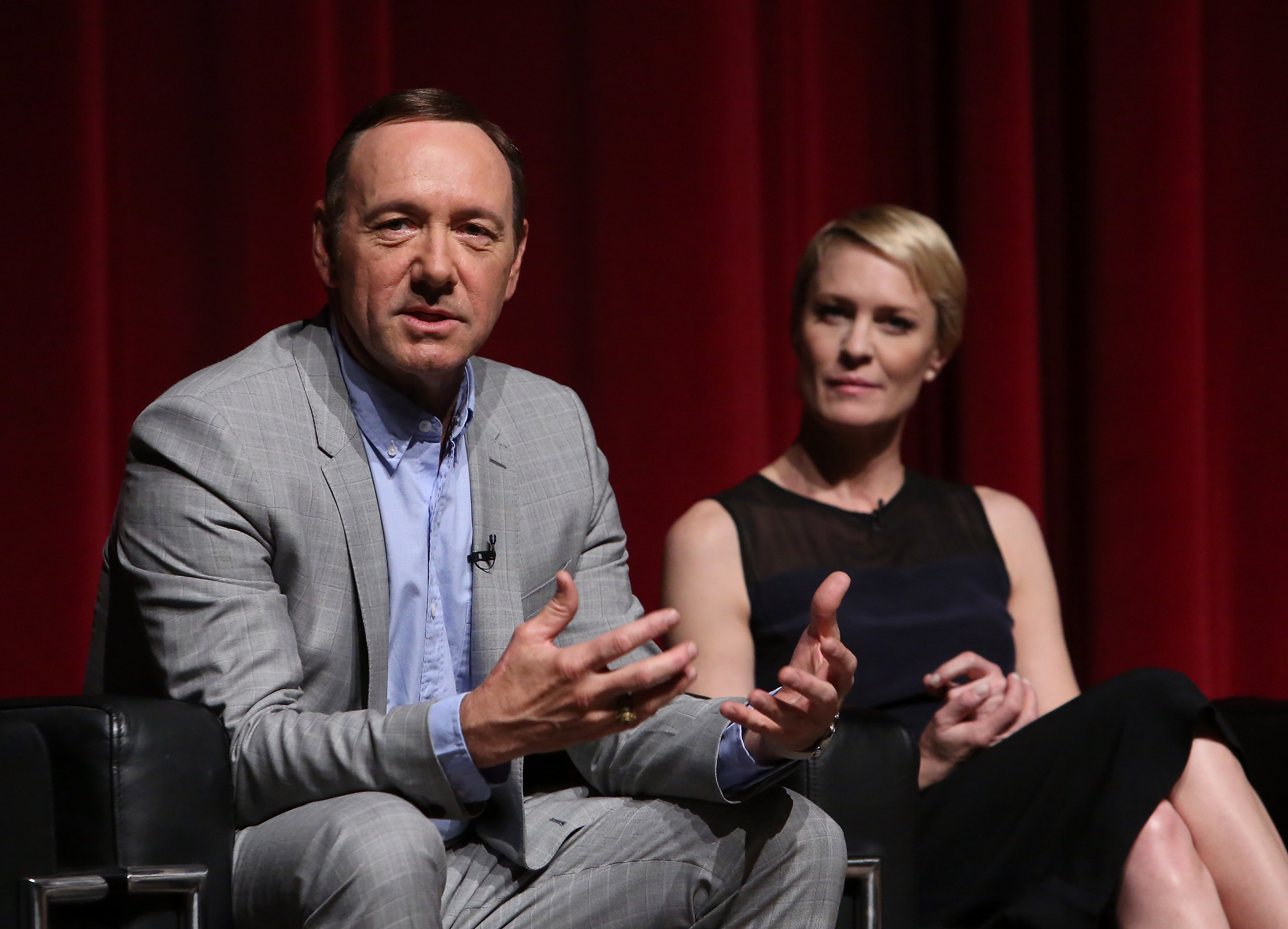

Judge unsure if Kevin Spacey case will 'continue or collapse' after accuser pleads the 5th

Judge unsure if Kevin Spacey case will 'continue or collapse' after accuser pleads the 5thSpeed Read

-

Devastating floods in Mozambique can now be seen from outer space

Devastating floods in Mozambique can now be seen from outer spaceSpeed Read

-

Robin Wright has finally commented on Kevin Spacey's sexual misconduct allegations

Robin Wright has finally commented on Kevin Spacey's sexual misconduct allegationsSpeed Read

-

Indiana science teacher stops middle school shooting: 'He's a hero today'

Indiana science teacher stops middle school shooting: 'He's a hero today'Speed Read

-

Here's how Ridley Scott replaced Kevin Spacey in All the Money in the World

Here's how Ridley Scott replaced Kevin Spacey in All the Money in the WorldSpeed Read

-

Kevin Spacey cut from completed Ridley Scott movie, replaced by Christopher Plummer

Kevin Spacey cut from completed Ridley Scott movie, replaced by Christopher PlummerSpeed Read

-

Netflix cuts ties with Spacey as sexual assault allegations snowball

Netflix cuts ties with Spacey as sexual assault allegations snowballSpeed Read