Can you protest racism on campus after the Paris attacks? Of course you can.

On our myopic hierarchy of suffering

The headlines pile up, the images, the outrage, the horrors. Anger and heartbreak, in three directions, five directions, 12, all pulling at our attention and time, our sympathy and tears. It's perhaps inevitable that humans (animals who, like all animals, are hardwired to assess risk) tend to rank these horrors as they unfold, a never-ending Olympics of Suffering.

The relentlessness of the news cycle doesn't help: Racism on college campuses was headline news until terrorism in Paris pushed it off. Earlier, protests at the University of Missouri had supplanted clashes in Jerusalem, which in turn had replaced Europe's refugee crisis, which pushed out police brutality, which overcame Bill Cosby. And did we mention Yemen? The bombings in Turkey? How about 9-year-old Tyshawn Lee, executed in a Chicago alley for the crime of being his father's son?

Immediately following the violence in France, a surprising number of people took to the airways and social media to argue the merits of the latest headline turnover, saying that now maybe the whiny PC police would have something better to think about:

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Perhaps this is not surprising. There are some for whom the Olympics of Suffering is the stuff of sustenance, the very foundation of their worldview and professional aspirations.

Yet even for those of us who haven't built our careers on dismissing the legitimate concerns of aggrieved people, it can feel as though we need to pick and choose: How can I worry about individual women assaulted by America's Dad if I'm also worried about systemic racism? How can I advocate for the resettlement of refugees fleeing civil war if I ache for the families of victims in France?

The answer is that we just can. The human mind is a complex machine, capable of holding more than one thought at once, capable of seeking racial justice and an end to sexual violence, even as we grieve for blood spilled and nations devastated. The hierarchy of need — the many before the few, the few before the one — does not invalidate anyone's need, nor does it mean that any one person or community can decide for everyone else what their hierarchy of need should be.

The human heart is also complex, and our capacity for compassion bottomless — but we're not required to carry all that pain, all the time. We can share the load, and trust each other to carry it with us. I'm often focused on American gun violence, and so am grateful to those focused on American health care; I'm often focused on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and so am grateful to those focused on Mexican drug cartels. No one's born knowing everything; no one can keep up with all the world's events as they spill across our screens.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Beyond that, though, is the fact that humanity's pain is exhausting. There are days on which — even for the most dedicated social activist, most dedicated voter, most kindhearted human — the world is too much. Days when we have to step away and sleep, dream, watch Star Wars trailers. In fact, when we refuse to do so — when we insist that personal needs cannot possibly compare with the world's and must be shut down — we invite a kind of psychic burnout that can ultimately incapacitate both our compassion and our engagement with the rest of the planet.

Arguing over who has the right to pain and empathy is a damaging distraction, and it posits binaries that don't exist and never have. No one's story is simple, no one's suffering is without context and history. I believe that we must start from a place of privileging the weak over the powerful, but that distinction is sometimes not as straightforward as we'd like. We have to listen for nuance, admit to ambiguity, and be forthright about our own failings and limitations. It's not easy, but it's eminently human.

So who has more of a claim to my concern: the young Parisian playing dead to save her life, the Syrian family braving stormy seas for the same reason, or the campus activists continuing the struggle for genuine equality for all Americans? I know some people have a simple answer to that question; I don't.

"We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality," Dr. King wrote from a Birmingham jail cell, "tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly."

To the extent that we can remain open to the reality of all human suffering, we must — but we'll never get it right. We'll always lurch from one story to the next, at best constantly seeking a balance that's not only illusive but probably impossible. But we mustn't desist from the effort. From Missouri to Paris to Syria, we're tied in a single garment of destiny.

Emily L. Hauser is a long-time commentary writer. Her work has appeared in a variety of outlets, including The Daily Beast, Haaretz, The Forward, Chicago Tribune, and The Dallas Morning News, where she has looked at a wide range of topics, from helmet laws to forgetfulness to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

-

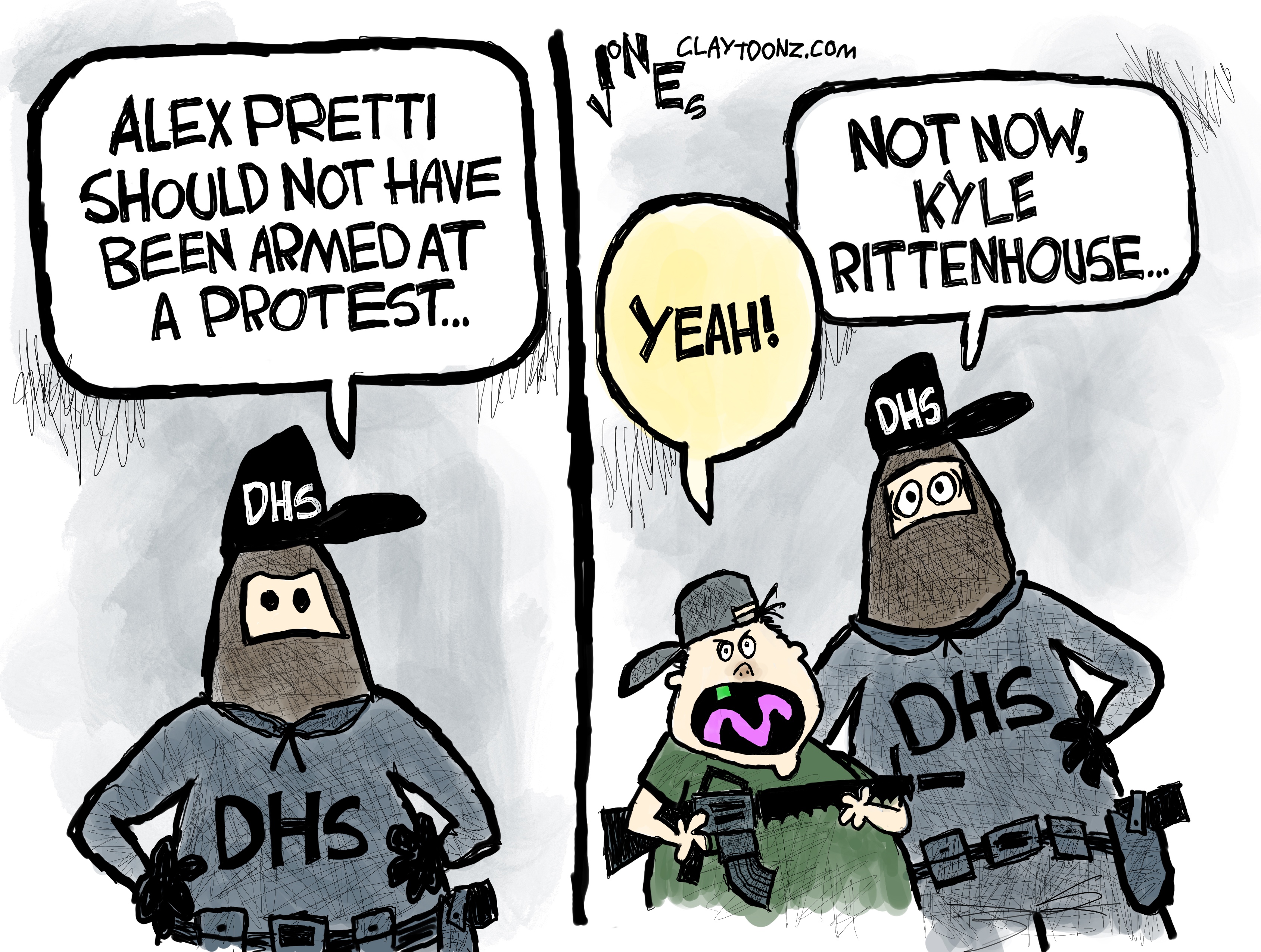

5 highly hypocritical cartoons about the Second Amendment

5 highly hypocritical cartoons about the Second AmendmentCartoons Artists take on Kyle Rittenhouse, the blame game, and more

-

‘Ghost students’ are stealing millions in student aid

‘Ghost students’ are stealing millions in student aidIn the Spotlight AI has enabled the scam to spread into community colleges around the country

-

A running list of everything Donald Trump’s administration, including the president, has said about his health

A running list of everything Donald Trump’s administration, including the president, has said about his healthIn Depth Some in the White House have claimed Trump has near-superhuman abilities