How to fix Hollywood's diversity problem

If the Academy, the studios, and entertainment journalists do a few simple things, Hollywood's diversity problem can be fixed. It won't even take very long.

In any other year, this would be the time when critics and analysts would be tripping over themselves to predict the frontrunners for this year's Academy Awards. But this year, the focus hasn't moved to the films that made the cut. It has stayed on the films that didn't. Each of this year's eight best picture nominees centers on a white protagonist. All 20 of the acting nominees are white.

Even the movies that did offer something different earned nods in categories that favored the white people involved in making them. Creed — a film written by, directed by, and starring black men — earned its sole Oscar nomination for white supporting actor Sylvester Stallone. Straight Outta Compton seemed like a possible best picture contender, but it too walked away with one nomination — for its white team of screenwriters.

It's a particularly disappointing outcome in a year full of box-office receipts that indicate the public is eager to embrace diversity. Star Wars: The Force Awakens smashed every record in the books this winter with no white men among its three protagonists. Furious 7 did the same with an even more diverse cast and crew. Creed successfully resurrected a decades-old franchise, and Straight Outta Compton made nearly eight times its production budget in worldwide box office.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

So when you see so few Oscar nominations for people of color for the second year in a row — which is saying nothing of nearly every other year's racially under-representative crop of Oscar nominees — it's discouraging.

The situation becomes even more complicated when considering solutions. Do you count on the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences to lead the way? Does change need to come from the studios? Should the Hollywood press take on the role of advocate?

The answer to all three questions is yes. A truly inclusive Hollywood needs to come from a comprehensive, deliberate strategy that mixes long-term change with short-term fixes. I have a few suggestions.

It starts with the Academy, which has already taken tentative steps. One week after the Oscar nominations were announced, President Cheryl Boone Isaacs called an emergency meeting of the organization's board of governors to discuss the problem of diversity and the Oscars. The result: a vague but theoretically encouraging plan to double the number of "women and diverse members" in the Academy by 2020.

Isaacs, as Academy president, will have the power to appoint three new governors. From there, the next steps should be simple: The Academy should designate one or all of these new governors as official ambassadors for inclusion. These men and women can work throughout the year to support actors, directors, writers, producers, and other cinematic storytellers of color. They can also advocate for those filmmakers to the broader voting body that might not know, for example, why Tangerine is such a novel achievement. They can organize screenings of and talks about films that speak to what should be a core Academy value: honoring the best achievements in a film industry that represents all people and points of view.

If anything, the studios have even more opportunity to initiate rapid change. If Hollywood needs to find an industry that faced a similar problem and addressed it aggressively, look no further than professional football. Prior to the 2003 season, only six minority men had ever been hired as NFL head coaches, and the 2002 season ended with the unexpected firing of the only two that were active.

Then-commissioner Paul Tagliabue teamed with civil rights attorneys and a diverse commission of former players, coaches, and other football personnel to enact something called the "Rooney Rule." Named after Dan Rooney, the owner of the Pittsburgh Steelers, it required franchises in search of a new head coach or senior front office executive to interview at least one candidate of color. The result: Within three years, the percentage of African-American coaches jumped from six to 22. And the percentage of coaching vacancies filled by minorities since the rule was implemented has risen to 20 percent.

I'm not alone in thinking Hollywood could benefit from a similar approach; Spike Lee mentioned the Rooney Rule by name in a recent interview on Good Morning America. The question is how to translate the rule to an industry with a need for more men and women of color in every component.

Like the Academy, every studio should employ an inclusion officer or officers to be in the room when Hollywood decision-makers greenlight films and hire creative talent. When casting for an original role in major studio movies, for instance, studios executives could require casting directors to audition at least one actor or actress of color for every part. Vanilla white men lead box-office bombs year after year, and bringing in someone who looks and thinks differently to audition for a big part could unlock all kinds of ideas for the creative team behind a film, resulting in a true win-win. This might not work for every movie, but there are plenty of roles that could benefit from colorblind casting.

Each studio should also pledge to make at least one film per year that's born from the creative vision of a racial minority, female, or LGBT filmmaker. You can't say there's no money for it; according to Forbes, Disney's film division netted $1.7 billion in 2014. That same year, Warner Bros. profited $1.2 billion, Universal made $711 million, and the year's worst-performing major studio, Paramount, still walked away with $219 million in net revenue.

Finally, the Hollywood press needs to think hard about its own role in the Oscar race. The two biggest trade publications, Variety and The Hollywood Reporter, spend months creating and shaping the Oscar narrative, and both have been justly criticized for not doing more to promote men and women of color. The latter ran a controversial cover story late last year for its annual "Oscar actress roundtable" issue, which is published well before the actual Best Actress nominees have been announced — and for the second year running, all the women featured were white. Knowing the publication would get hit with backlash upon its release, executive editor Stephen Galloway pre-emptively penned an exculpatory letter to readers, claiming he and his fellow editors searched for a woman of color to include in this conversation, but "discovered precisely zero actresses of color in the Oscar conversation."

It seems The Hollywood Reporter has no faith in its own ability to influence the best actress narrative. If the magazine had taken a more active role, the roundtable could have included deserving contenders like Creed's Tessa Thompson, Chi-raq's Teynoah Parris, or Tangerine's Kitani Kiki Rodriguez and Mya Taylor. There's a reason major studios vie to get their stars on the cover of a publication like The Hollywood Reporter: because it explicitly defines them as contenders worthy of a voter's attention, and gets them in front of an audience of millions — many of whom work in the industry.

It's true that Hollywood's diversity problem goes well beyond the Academy. Where the organization can't be defended, however, is in its utter failure in years past to step up and lead. You can come up with all the ideas in the world — but without the industry's biggest players stepping up, nothing will change, and we'll be here next year, scratching our heads and wondering: How did we let #OscarsSoWhite happen again? Fortunately, this year's failures come with the renewed reminder that there are plenty of ways to turn it all around.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

John Gilpatrick is a freelance film critic and former member of the Men's Health magazine digital team. He is a member of the Online Film Critics Society. You can read his reviews and more at JohnLikesMovies.com.

-

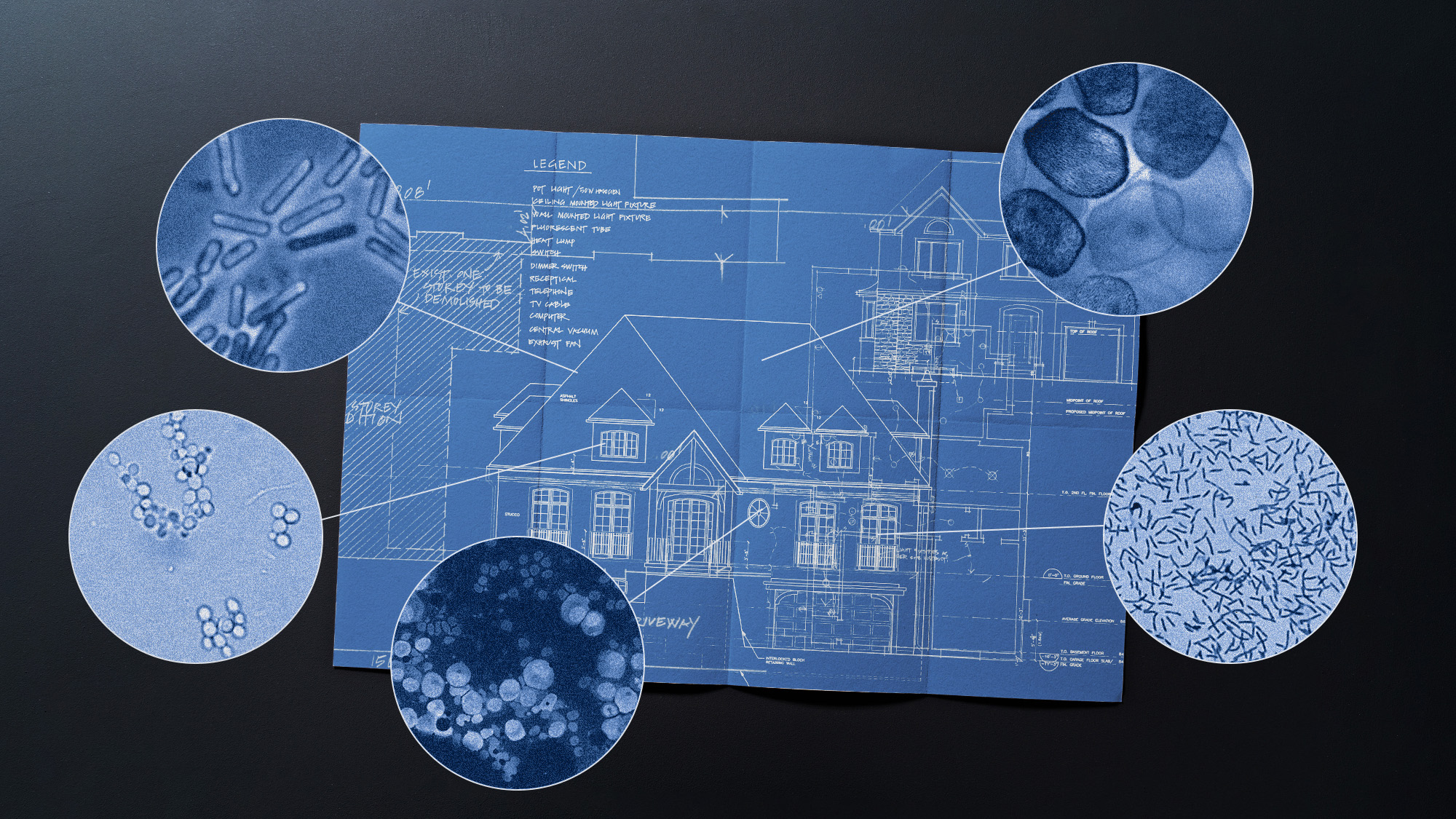

How to create a healthy 'germier' home

How to create a healthy 'germier' homeUnder The Radar Exposure to a broad range of microbes can enhance our immune system, especially during childhood

-

George Floyd: Did Black Lives Matter fail?

George Floyd: Did Black Lives Matter fail?Feature The momentum for change fades as the Black Lives Matter Plaza is scrubbed clean

-

National debt: Why Congress no longer cares

National debt: Why Congress no longer caresFeature Rising interest rates, tariffs and Trump's 'big, beautiful' bill could sent the national debt soaring

-

Walter Isaacson's 'Elon Musk' can 'scarcely contain its subject'

Walter Isaacson's 'Elon Musk' can 'scarcely contain its subject'The latest biography on the elusive tech mogul is causing a stir among critics

-

Welcome to the new TheWeek.com!

Welcome to the new TheWeek.com!The Explainer Please allow us to reintroduce ourselves

-

The Oscars finale was a heartless disaster

The Oscars finale was a heartless disasterThe Explainer A calculated attempt at emotional manipulation goes very wrong

-

Most awkward awards show ever?

Most awkward awards show ever?The Explainer The best, worst, and most shocking moments from a chaotic Golden Globes

-

The possible silver lining to the Warner Bros. deal

The possible silver lining to the Warner Bros. dealThe Explainer Could what's terrible for theaters be good for creators?

-

Jeffrey Wright is the new 'narrator voice'

Jeffrey Wright is the new 'narrator voice'The Explainer Move over, Sam Elliott and Morgan Freeman

-

This week's literary events are the biggest award shows of 2020

This week's literary events are the biggest award shows of 2020feature So long, Oscar. Hello, Booker.

-

What She Dies Tomorrow can teach us about our unshakable obsession with mortality

What She Dies Tomorrow can teach us about our unshakable obsession with mortalityThe Explainer This film isn't about the pandemic. But it can help viewers confront their fears about death.