How one of my closest friends taught me how to die

Mike Brick, reporter and songwriter, died earlier this year at age 41. He taught his friends how to live, and how to die.

My wife remembers meeting Mike Brick on a subway car, en route to a Yankees game in the Bronx. Mike jumped on the train at the last minute, wearing a three-piece suit and fedora, looking everything like the 1940s newspaper reporter he may well have been.

I met Mike not too long before that day, around the turn of the millennium, and almost certainly at a bar or a music show. Fuzzy though the details may be, that's a fixed, important line in my life: Before Mike Brick, after Mike Brick.

Mike and I were young together, invulnerable. We were aspiring acoustic rock stars in New York City, but with day jobs.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Mike's day job was reporter, and after he took a break from newspapers he wrote for magazines. How seriously did he take his profession? In one delightfully madcap article about a Cannonball Run–style motorcycle race, Mike explained that after he arrived at the first checkpoint in Las Vegas, "I spent the next four days at the Orleans, a discount casino where I financed the rest of my reporting trip with a few successful sessions at the craps table." He had stories like that, and they were true.

On Jan. 13 of this year, Mike Brick strapped on his guitar, stepped up to a microphone in Austin, Texas, and gave the show of his life. "Looking back at it all, I didn't leave a thing on the table," he said. His long-scattered New York band was reunited behind him; dozens of friends, family members, and admirers were in front.

Three weeks later, Mike died.

I lost one of my closest friends. Mike's wife and three children lost considerably more.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Mike was only 41, killed by cancer.

People dying of a degenerative disease like cancer have things to teach us, if we choose to listen. The lessons are often hard to hear, and they are even harder to embrace. They are gifts that cost too much, horrible but not unspeakable. They are thrust on us, unwanted. But to ignore them is to squander something precious. Some of the gifts Mike left are tangible: his treasure box of songs; his binders worth of smart, dryly funny, improbably entertaining articles and essays; his family.

I will draw comfort from those parts of Mike that remain accessible. But it's the other gifts that may guide me somewhere else, somewhere better. Here's the biggest, most ungainly gift Mike left me: a visceral reminder of death.

Last year, in the warm Austin fall, when it wasn't clear if the chemotherapy was working, Mike would invite friends on walks, one at a time, presumably for company as well as exercise. I hope he got something more out of them; I know the rest of us did. On one of our walks, he told me he'd never imagined he would become "that guy," the person who makes everyone around him reconsider their priorities and, yes, appreciate their life in a new way.

Mike didn't seem angry about it. He knew that it's important to live, and to do that you have to accept that you will die.

The age 40 lies in that gray area between the blithely accepted immortality of youth and the wary acceptance of our impermanence that comes with later middle age. It may not seem like much of a bestowal, but Mike helped me and, I presume, other friends walk toward the other side of that vale. As Mike was dying, one of his friends tattooed on his arm the Latin phrase "Noli timere" (Don't be afraid) — the final words of the Irish poet Seamus Heaney, and the most frequent exhortation from Jesus in the four Gospels.

Steve Jobs told a class of graduating college seniors in 2005, when they were young and he'd just survived a bout with cancer, that "remembering you are going to die is the best way I know to avoid the trap of thinking you have something to lose." The German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche called "the certain prospect of death a precious, fragrant drop of frivolity" that made life worthwhile, spoiled only when we "singular druggist souls" poison the idea of death and make "the whole of life hideous."

Fearing death is perfectly normal and rational, but not being aware of it can make you forget to live. Mike was a great teacher here, too.

There are so many things I learned, or was forced to finally take to heart, from watching and being around Mike in his final year: Friends are worth actively keeping and acquiring. Be a pleasant, fun person to work with, and take pride in your labor. You're always more interesting to be around if you take a genuine interest in the people you are talking with. Mike consistently asked great, thoughtful questions and listened to the answers; even as he suffered a great deal of quiet pain and corporeal indignity during his last months and days, whenever you were thoughtless enough to come to him with a problem, he was invariably sympathetic or indignant or outraged on your behalf.

It is not a coincidence that Mike was surrounded by loved ones and well-wishers in his final weeks. As people gathered from various epochs of his life, the stories flowed and it became clear that Mike Brick had packed more into 41 years than many people fit in a much longer lifetime. Nobody gave him permission to do that. You don't need permission, either. These are each big lessons, even if they look a bit trite thrown together like that. I hope to incorporate at least two of them into my life, but even that modest goal will be a challenge.

That's one reason we write these gifts down.

After I met Mike Brick in New York, introduced by a mutual friend, his benefaction started almost immediately. A quickly rising newspaper reporter, he helped usher me into the journalism profession. Just as importantly, he invited me — a middling cellist who hadn't played since high school — into his band to anchor the rhythm section. We played around New York City, toured the middle East Coast twice, and then life took us separate ways. When, years later, Mike and I both ended up in Austin, I learned electric bass so I could help him form a new band.

Few people have had a bigger influence on my path in adult life. I hope he knew that.

Mike found out he had colon cancer last March, and that it had spread to his liver and other parts of his body. Even as he fought the multiplying cancer cells with chemotherapy and every other tool at his disposal, he decided early on that he wanted his battle — win or lose — to be graceful and brave and wise, to serve as a model for those of us not consciously fighting for our lives. It is hard knowing how to help someone battling cancer or another slow, degenerative disease. For some reason, Mike decided he had to help us. If only we know how to listen.

Mike was never quiet. From starting and fronting bands to earning his way onto the pages of major metropolitan newspapers, national magazines, and his own improbably entertaining and painstakingly reported book about saving a local Austin high school, Mike's life is an enduring endorsement of just going out and working on what you love, of not being afraid. Noli timere. It's not just a lesson for the young and fearless — in many ways, it's more important for the adult years. Don't cower in fear, and don't forget that every day counts. "Teach us to number our days," say the psalmists, "that we may gain a heart of wisdom."

Mike had a wise heart. It was never clear whether he was a musician or a reporter first — his obituary in the Houston Chronicle, his final employer, put "songwriter" first — but both vocations allowed him to share his wisdom, and he excelled at each. At his living wake, Mike listed his children as his "most important and proudest accomplishment in life."

None of his gifts — teaching us how to die, reminding us how to live, highlighting the importance of treasuring friends and loved ones — are unique to Mike. But he gave them freely, and at great cost.

And not a one of us would hesitate to return these gifts, this knowledge, if it would bring him back.

Peter has worked as a news and culture writer and editor at The Week since the site's launch in 2008. He covers politics, world affairs, religion and cultural currents. His journalism career began as a copy editor at a financial newswire and has included editorial positions at The New York Times Magazine, Facts on File, and Oregon State University.

-

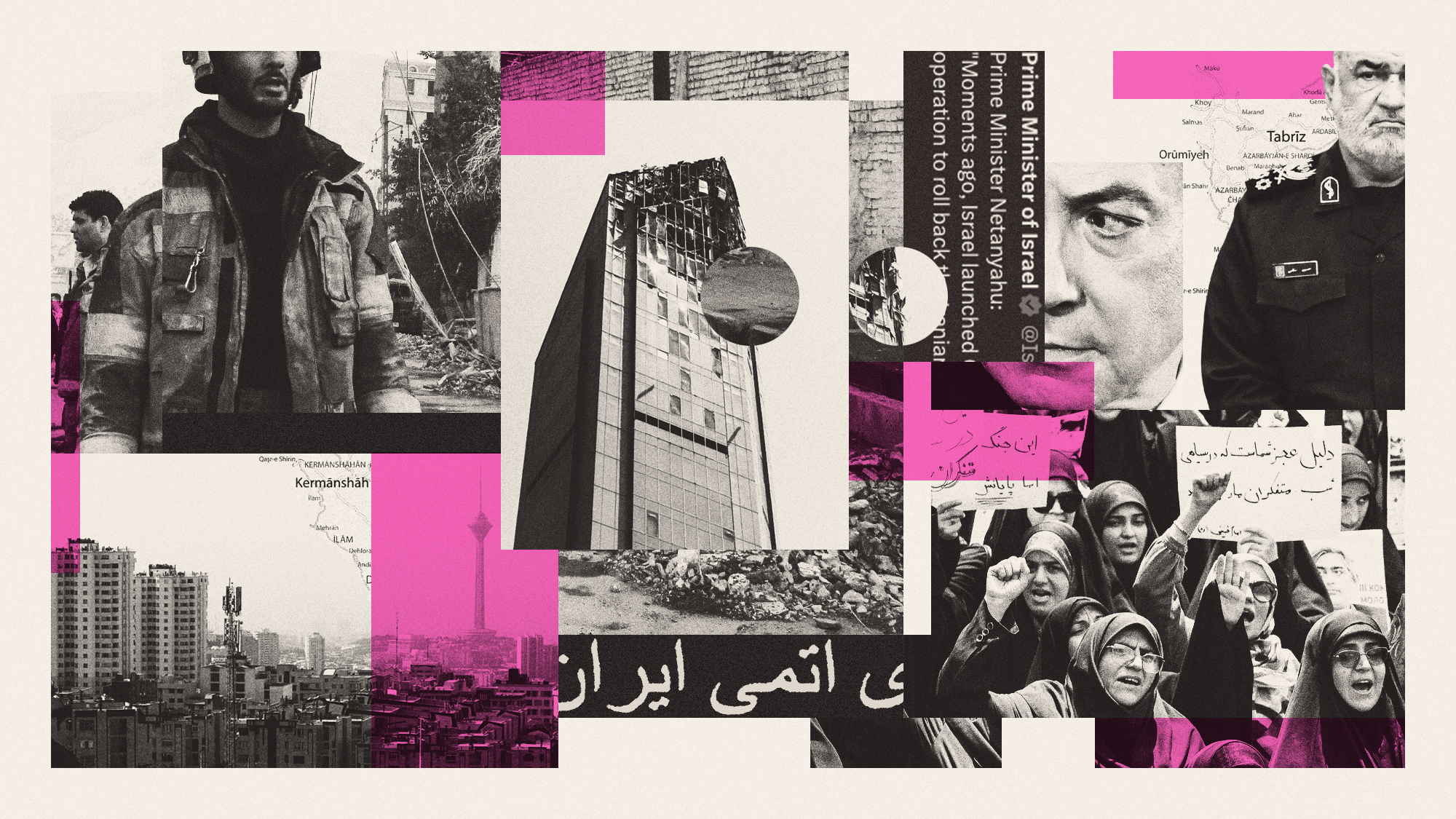

After Israel's brazen Iran attack, what's next for the region and the world?

After Israel's brazen Iran attack, what's next for the region and the world?TODAY'S BIG QUESTION After decades of saber-rattling, Israel's aerial assault on Iranian military targets has pushed the Middle East to the brink of all-out war

-

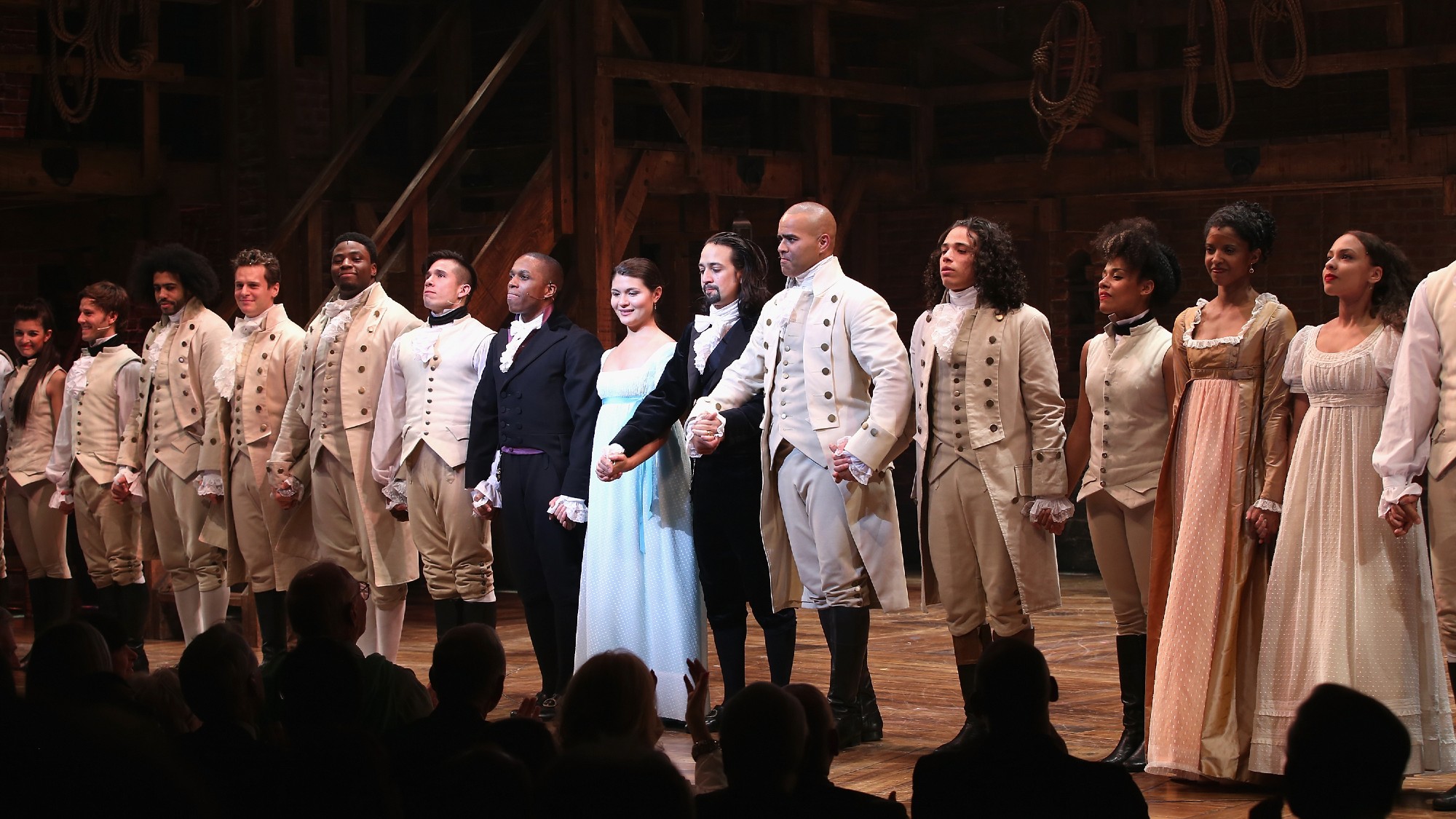

7 touring theater productions that are out to bring the joy

7 touring theater productions that are out to bring the joyThe Week Recommends 'Hamilton' and 'Wicked' never die, and neither does ABBA

-

College grads are seeking their first jobs. Is AI in the way?

College grads are seeking their first jobs. Is AI in the way?In The Spotlight Unemployment is rising for young professionals