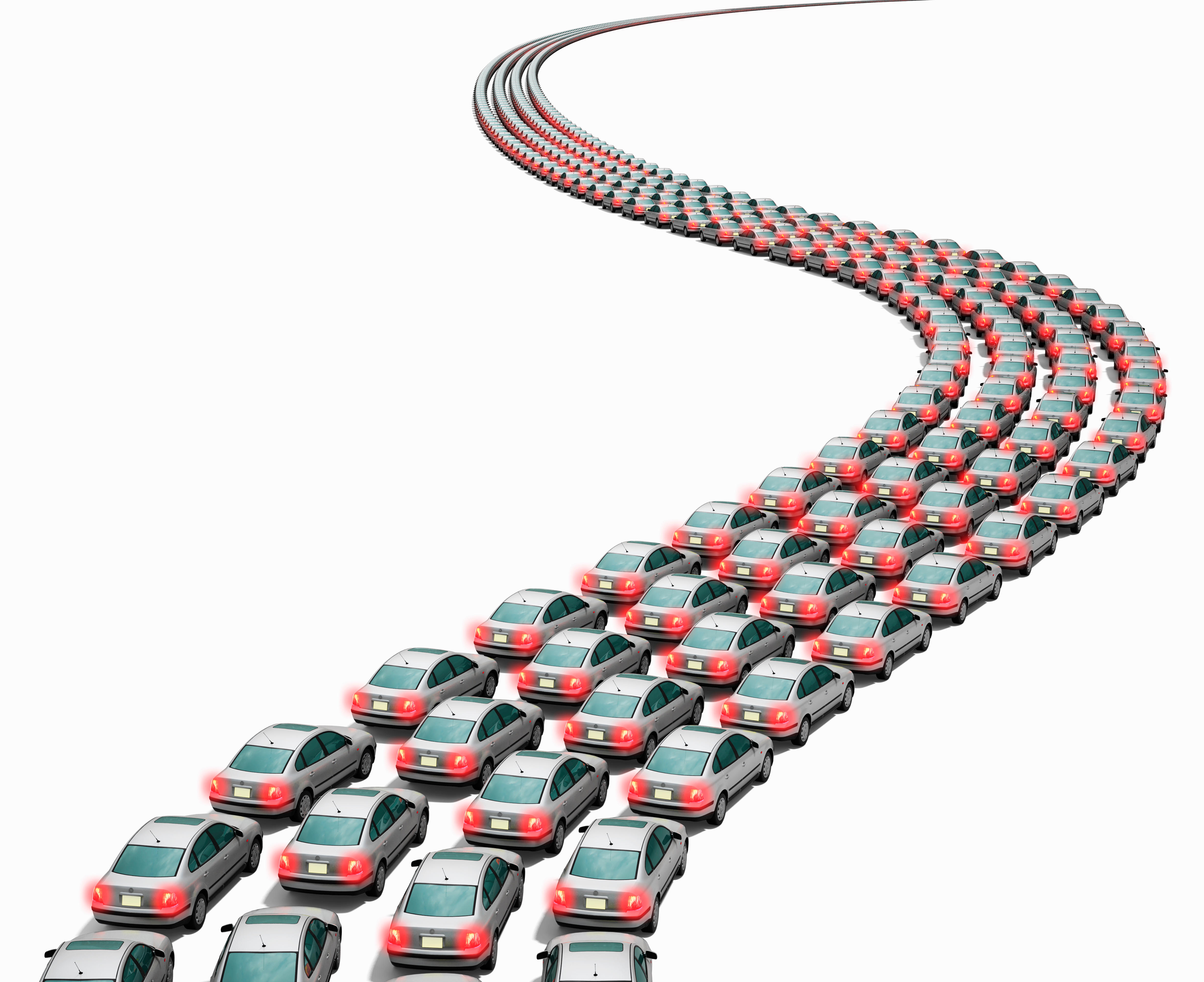

Uber may kill surge pricing. Don't start cheering just yet.

It might be good for riders, but it's absolutely terrible for drivers

Everyone knows about Uber's surge pricing. And it isn't exactly popular. Now, according to NPR, the company is working on a way to get rid of the model. The wrinkle is that some of Uber's own drivers are the ones wishing it would stick around.

To review: Surge pricing is an algorithm Uber uses that increases the cost of a ride in a particular area when demand for rides in that area goes up. In more dramatic moments when demand increases a lot — a snow storm in New York City and an armed hostage crisis in downtown Sidney are two real-world examples from recent years — the price can go up four or eight times its normal rate.

This has not always gone over well with Uber's customers. "I AM OUTRAGED AND DISGUSTED THAT YOU WOULD JACK UP YOUR CHARGES THAT MUCH BECAUSE OF A SNOW STORM!!!" one user wrote the company — capitalization theirs. (It actually got a Facebook response from Uber's CEO.)

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Now, as the company repeatedly pointed out, there's a standard Econ 101 justification for surge pricing: It coordinates supply with demand. Economists often refer to prices as "signals," and in the market for Uber rides, a surge in prices signals two things: It tells customers a lot more people want Uber rides than usual right now, so maybe don't buy one unless you really need it. And it tells Uber drivers who aren't working that a lot more people want rides, so get out there and make more money. That way big surges in demand are met with big surges for cars.

The price spikes may be a PR problem for Uber, but without them the company would arguably just have another PR problem: Floods of riders who can't find a car, period. (This would be the case even if surge pricing only relocates drivers already on the road to high-demand areas, as one study suggests.)

But it stands to reason Uber would like it even more if they didn't have to deal with either PR problem. That's where their new project comes in. Jeff Schneider, the engineering lead at Uber Advanced Technologies Center, told NPR the goal is to use "machine learning" to create new algorithms that anticipate demand surges, rather than merely hiking prices in response. As NPR laid out, Uber drivers constantly keep their ears to the ground, tracking sporting events, business conferences, conventions, and even fraternity and sorority parties on university campuses to anticipate when surge pricing might hit. But in the modern age of data abundance, computers could do that research for them, spit out predictions ahead of time about when and where demand will spike, and then direct drivers accordingly.

"Find those Tuesday nights when it's not even raining and for some reason there's demand — and to know that's coming," as Schneider put it. "That's machine learning."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Think of it as doing the work of the price signal, but without the price.

But as several Uber drivers also told NPR, that could be a problem for their pocketbooks. "Surge is absolutely make or break," David Thrasher, a driver in Atlanta, said. "If there was no surge, ever, I wouldn't be able to afford doing this at all." Surge pricing in some weeks can knock his pay rate up from around $11 an hour to $16 or $17 an hour. Another driver showed NPR pay stubs where surge pricing accounted for a quarter of his income, increasing it by almost $700 a month.

So if Uber can get this machine learning to work, will that be an example of robots and automation taking American jobs?

Well, you can certainly think of the surge price as payment to workers for doing that research about looming demand spikes themselves. So if Uber can get computers to do that research, they can get rid of that additional payment.

But there's also this: Uber wouldn't make the change unless they thought it would make them more money. Maybe the new algorithms will work better than the surge pricing. Maybe more customers will use Uber if surge pricing is eliminated. Those scenarios could result in more rides, in which case drivers could make up the lost revenue with more fares. But if drivers' fears are born out, and the elimination of surge pricing permanently lowers their pay, the important thing to realize is that Uber the company is still making more money than it did before. The new revenue isn't going to the drivers, but it's going somewhere — i.e. the owners and shareholders.

This gets at a subtle but crucial distinction in the debate over automation that often gets glossed over. Companies adopt new technologies when they think it will improve the bottom line — more revenues, less costs, and thus higher profits. This is only a problem for workers if they can't lay claim to a share of that new revenue. So the problem isn't the new technology. It's that workers need the leverage to demand better pay, and right now they don't have it. As one of the drivers told NPR, Uber sets the rates and drivers just take it: "There's no conversation about it. The end."

One obvious way to get workers back in on that conversation is to rebuild unions. And efforts are already underway to help drivers for Uber and Lyft unionize.

Technology scares us because it disrupts existing ways of doing business and existing pay structures. But that's only a problem if workers can't demand a new pay structure, just as good or better, to replace the old one. To make that demand, and to make it stick, workers need power.

That's what's really been lacking in the modern age of automation.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.