Goodbye again: What it's like to lose both parents to Alzheimer's

When both my parents were diagnosed with a devastating disease, I had to learn, and re-learn, how to let them go

Goodbye. Goodbye. Goodbye. Goodbye.

You've heard it. Of course you have. Alzheimer's disease is the long goodbye. The body is present but the mind is gone.

Alzheimer's is nothing like amnesia. It's nothing like cancer. It's nothing like dying unexpectedly in a car crash. And it's not something you'll fully understand unless a loved one is felled by it, as both my parents were.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Mom and Dad were 38 and 46, respectively, when I was born. Dad was a lapsed Mormon, a first-generation American of Welsh and Scottish stock. He was six feet tall with dazzling blue eyes, and looked like Fred Astaire with a million-watt smile and an easy, elegant charm about him. He was a photographer during WWII and worked alongside famed LIFE magazine photographer Carl Mydans. They were such good friends that Dad named me after Carl's wife, Shelly, but added an extra 'e' for show. He was a self-employed, jack-of-all-trades who did well enough to retire at 40.

Mom was a devout Catholic from the Philippines, a daughter of a Filipino widow of a Chinese husband who fled to Manila to escape communism in the 1920s. She was an Asian Marilyn Monroe with a brick-house figure; an exotic, 4-foot 10-inch, 98-pound China doll who worked for the U.S. government with top security clearance for decades.

They were a stunning couple.

My parents made it to their 50th wedding anniversary. Then, one after the other, five years apart, my parents died.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Their lives with — and deaths from — Alzheimer's could not have been more different. Yet my process of saying goodbye was the same: silent and slow. I had to say goodbye at the diagnosis. I had to say goodbye during their blank stares when they saw me as a stranger rather than recognized me as their beloved child. And I had to say goodbye when their bodies followed their minds into the ether and whatever lay beyond.

"Come here, sweetheart," my dad said softly as he beckoned me with a smile. I was five years old and his only child. I snuggled in his arms, feeling the stubble of his day-old beard against my face.

"Sweetheart, if I ever get sick and can't speak or see or take care of myself, promise me that you'll never put me in an old folks home. Please take care of things so I don't suffer." I crossed my heart and hoped to die and made the promise. I thought it meant I would bring him a blanket and some milk.

Forty years later, I sat at his bedside in a nursing facility, a place where, after 10 years of fighting this bastard disease, he finally ended up after a series of falls that rendered my mother so grief-stricken that she couldn't safely look after him anymore.

The descent began when my husband Mike and I noticed Dad was becoming forgetful. But he was 80 years old, so it wasn't alarming. He and Mom still lived independently in their own home. He was jubilantly defiant when he passed his driving test at 80 with flying colors.

"Damn right!" Dad bellowed, jabbing his fist into the air. "I've driven since I was 8 years old. I've still got it! Like my mug shot, honey?" he proudly held out his new license.

But over time, little signs started appearing. Three years of increasingly endless repetitive questions were followed by viciously angry outbursts over rescheduled medical appointments or preempted TV shows. Then came the calls. Dad would call us at all hours of the day to ask questions about obscure topics: the news, peanut butter sandwiches, baseball. And in the last year of his life, he slept a lot during the day and kept Mom awake at night. He would grasp at invisible cords he thought were hanging from the ceiling and talk to the TV because he thought the sports announcer was standing in his living room.

His doctor diagnosed Dad with mid-stage Alzheimer's disease. We learned never to argue with him because it would agitate him. We took away his car keys but still fretted about him wandering off and injuring himself or getting hopelessly lost. Our days and nights were fraught with tension as we constantly anticipated a phone call bringing bad news. Would he lash out at a stranger in a coffee shop? Would he fall while Mom was sleeping and be alone, scared, and hurt? Would he unknowingly hurt Mom? If he injured someone, would they sue him and take his house?

Then he fell and cut his head badly. He was admitted to the hospital for stitches and observation. We were told he had two weeks to live because he didn't remember how to eat by himself and resisted being fed by nurses. After the first week passed, we transferred him to a skilled nursing facility. The promise I'd made 40 years earlier rang in my ears and made my heart heavy with sorrow and guilt. I reminded myself that it was the safest thing to do, regardless of that promise. If he stayed at home, he could die in agony from an accident. Mom could hurt herself trying to lift him. It had to be this way. After all, the doctors said two weeks. He surely could forgive me for that. Were we doing the right thing? Yes. No. Yes. No. Yes.

But Dad lived for nearly three more months. I spent hours with him every day, watching him sleep, listening to his stories and wondering who he was talking to when he had conversations with invisible beings in the corner of the room. He thought his nurses were old friends. He laughed with them and told them war stories. And he ate.

There were moments, sometimes even hours, when he recognized me and knew where he was. And in those moments, he was so weary. One day, I found him dressed in white pajamas sitting in a recliner outside of his room with a white face towel on top of his head.

"Hi pumpkin."

He'd never, ever called me that before. I wondered if he knew I was his daughter. But then he smiled, and I knew he recognized me.

"The nice lady just gave me a bath," he said. "I feel clean. She's making my bed now. Where's Mike?"

I told him that Mike was running late but he'd be there for lunch. I hugged him gently and kissed his cheek. He smelled like Ivory soap.

"I love you, Daddy."

He closed his eyes and said very softly, "I know."

There was no "I love you too, sweetheart," or "I love you more." Just that simple acknowledgment of my adoration for him.

He couldn't eat solid food easily. Every meal was pureed and looked like oatmeal. Green oatmeal. Orange oatmeal. Cream colored oatmeal. Jell-O was the only solid food he could eat without struggling and he always grabbed it first. I brought him chocolate milk, which he drank as if it was the elixir of eternal life. One day I smuggled in a Coke. It was his favorite drink. He took the bottle from me and held it lovingly. He recognized it instantly. He opened the bottle and guzzled it all in one swig and immediately let out a raucous burp. He turned to me, his sweet old self, with his beautiful smile and light blue eyes and blew me a kiss.

"Thank you honey. That was my favorite."

That was the last time we spoke.

Dad slept all day and stayed awake and agitated all night. He couldn't speak well and eating was reduced to sucking on sponge lollipops dipped in ice water. The hospice nurses were called in. The time was near. A week at most, they said.

The next day was Dad's last. I didn't know it would be. I spent nine hours with him. He slept the whole day and his breathing was faint. I held his hand and played "Moon River" and "The Sound of Music" to him on the CD player. I told him about a job I was hoping to land. I took a picture of his hands.

An hour after I left, Dad died.

Mom was scared to live alone, so Mike and I moved into her house. She demanded we not "cramp her style," which meant her daily rituals of church, lunch at McDonald's, shopping at CostCo, and watching Judge Judy. She loved playing with our new rescue bulldog, Boris.

Boris was the tip-off that something was amiss. We warned Mom only to feed him dog food and a daily dog treat. But within one year, he had gained eight pounds, and we discovered Mom had been surreptitiously feeding him bacon. Each time we warned her, she would roll her eyes and giggle. The Mom I knew would never knowingly hurt any creature.

From there, her descent into Alzheimer's was very different from Dad's. For her, it started with language.

"Anak," she whispered to me in Tagalog — one of the three languages she spoke. I knew she was calling me "baby," but I had to stop her before she started telling an entire story in another language.

"Mom, I don't understand you," I said. She gazed at me with wonder, as if she was seeing me for the first time. Then a minute later, she recognized me. Her eyes widened and she burst into a huge smile. "Oh, honey. HA HA! Your old mom is getting forgetful."

Another clue came when we witnessed her dwindling sense of fashion. Mom always dressed to the nines and never left the house unless she was perfectly made-up, perfumed, and attired. Over the course of a few years, she morphed into an eccentric little old lady with mismatched socks and thrift store jackets. But at least there was some of the old Mom still there when she would come to us for help.

"Umm, Shelley," was all she could manage as she sheepishly held out an eyebrow pencil. She was getting ready for church. Her blouse was buttoned crookedly. The one brow she had managed to sketch in was Elizabeth Taylor-ish, so I fixed it and carefully drew in the other one. She smiled with gratitude and kissed me.

And she was fine until the last three days. On Friday the 13th, we found her sleeping on the floor. Mike woke her and asked if she knew where she was. "In my bed," she replied tentatively. She was burning up and slurring her words. She couldn't even sit upright in a chair by herself.

The ER doctor diagnosed sepsis. Doctors buzzed in and out of the ICU. A cardiologist. A urologist. An oncologist. She needed a full-face oxygen mask to stabilize her breathing and blood pressure. She absolutely hated the mask and kept trying to tear it off. Every time we replaced it, she would pound her fist into the pillow on her lap and shake her head. Only later did we realize that Mom didn't want it at all. She wanted to be free.

Within 10 minutes of removing the mask, the pain in her face had gone and her breathing slowed. Mike and I held her hands as she took her last breath.

It was over. Just like that. For both of them. They wanted to be cremated and we honored that. And we scattered their ashes — and Boris' — under the pine trees in our yard.

Dad, drive like you're at LeMans. Mom, feed bacon to Boris. Boris, run free on Rainbow Bridge.

I thought I was done with goodbyes. But I still dream about them. My first dreams were so vivid that I'd wake up in tears because I thought they were still alive. Goodbye. Then I went through a phase of dreams where seeing them made me angry because I feared I'd have to go through their deaths all over again. Goodbye.

When I dream of them now, I feel they're just popping in to remind me that they love me. But each dream, each memory, still brings forth a little reliving of their lives, their disease, and their deaths. Sometimes I laugh and sometimes I weep. Sometimes I wish they were still here and other times I feel it's fine that they're not. There are even times when I feel nothing. But always and forever, like the deep soft drone of a monk's endless chant, I will be saying goodbye.

Shelley Moench-Kelly is a freelance writer and editor from Vermont via Los Angeles and Tokyo. Her freelance clients include Google, L'Oreal Paris, and MedEsthetics magazine.

-

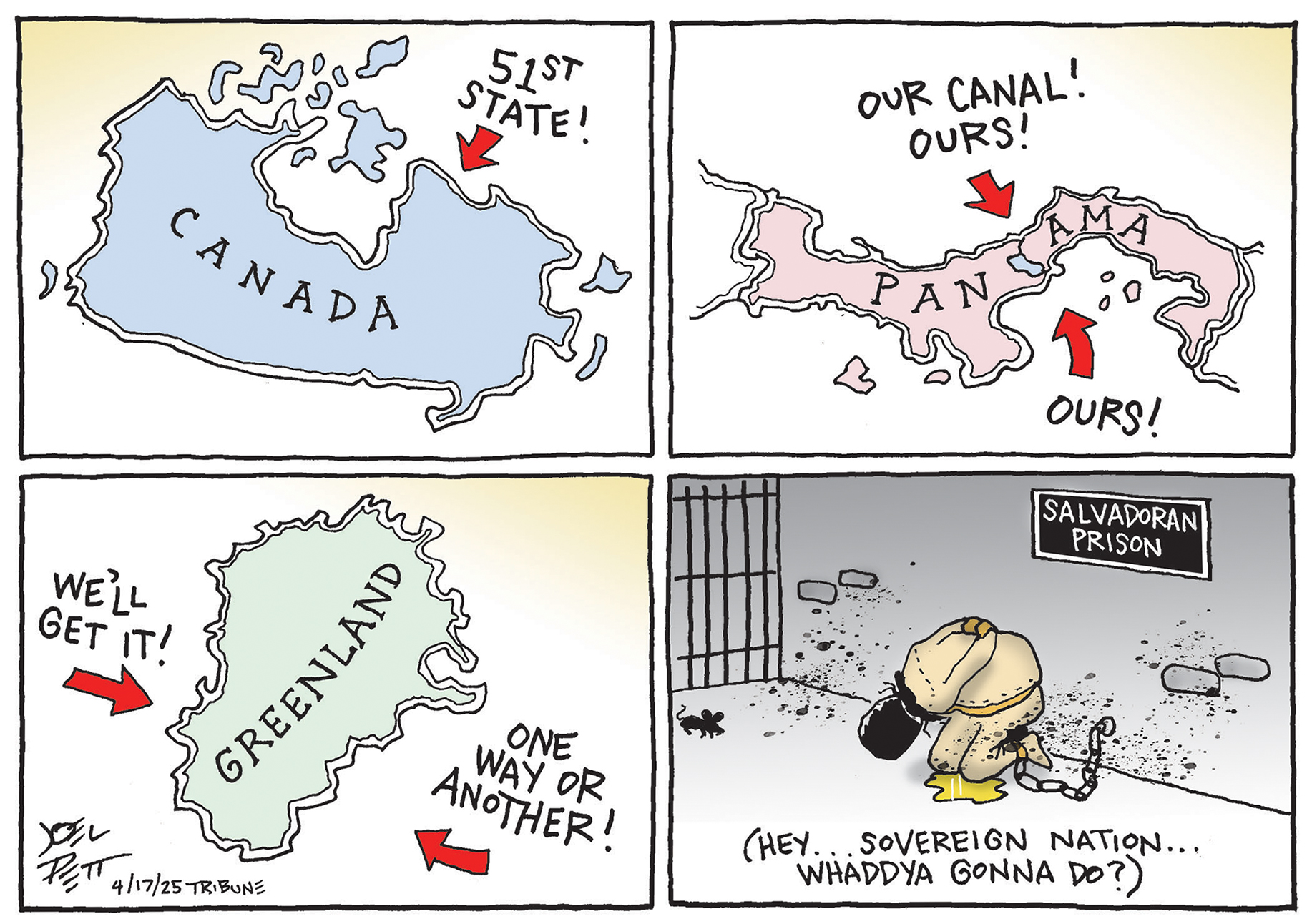

Today's political cartoons - April 18, 2025

Today's political cartoons - April 18, 2025Cartoons Friday's cartoons - El Salvador, political fundraising, and more

By The Week US

-

The week's best photos

The week's best photosIn Pictures A sea of kites, a game of sand hockey, and more

By Anahi Valenzuela, The Week US

-

G20: Viola Davis stars in 'ludicrous' but fun action thriller

G20: Viola Davis stars in 'ludicrous' but fun action thrillerThe Week Recommends The award-winning actress plays the 'swashbuckling American president' in this newly released Prime Video film

By The Week UK