Olympic doping, explained

Russia's entire track-and-field team has been banned from the Rio Olympics. Do other athletes dope, too? Here's everything you need to know.

Russia's entire track-and-field team has been banned from the Rio Olympics. Do other athletes dope, too? Here's everything you need to know:

Why were the Russians banned?

Investigators found that Russia had for many years been running a massive, state-sponsored doping program for its athletes. The allegations first came to light in a 2014 German TV documentary, in which whistleblowers claimed "99 percent" of Russian athletes used banned substances, and that Russian officials both supplied the drugs and colluded with doping-control officials to cover up failed tests. One athlete said she had paid the Russian Athletics Federation $450,000 to keep secret a positive test. In a devastating report last year, investigators for the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) concluded that Russia had been running a "state-supported" doping program dating back to at least the 2008 Beijing Olympics. It alleged that the country's anti-doping agency — with the help of the FSB, Russia's security services — routinely gave athletes advance notice of tests, bullied doping testers and their families, and intentionally destroyed positive test samples. "It's worse than we thought," said Dick Pound, the report's author. "This is an old attitude from the Cold War days."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Has Russia admitted any wrongdoing?

Not really. Sports Minister Vitaly Mutko apologized for the failures of Russia's anti-doping system, but he blamed individual athletes and refused to admit any state involvement. Dr. Grigory Rodchenkov, the former director of Russia's main anti-doping laboratory, painted a very different picture. Now in hiding in the U.S., Rodchenkov revealed that at the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi, a secret lab was set up in the room next to the sealed-off WADA testing area. At night, Russian anti-doping officials passed athletes' urine samples through a tiny hole in the wall to the secret lab; the tainted samples were then replaced with clean urine and returned through the hole to the testing area. Russia topped the medal count in Sochi, after having finished 11th in the previous Winter Olympics in Vancouver.

How prevalent is doping?

Russia isn't the first country with a state-sponsored drug program. In the 1970s and '80s, the Communist regime in East Germany forced as many as 10,000 athletes — many without their knowledge — to take anabolic steroids, a synthetic version of the male sex hormone testosterone. These drugs, which are still the most popular form of doping today, enable athletes to train harder, recover faster, and build more muscle. But they had a devastating effect on East Germany's female athletes, who suffered from side effects including unusual hair growth, deepened voices, and fertility issues. Several Olympic athletes — mainly weightlifters — were caught for steroid abuse during the 1970s and early '80s, but the issue really came to the public's attention when Canadian sprinter Ben Johnson was stripped of his gold medal at the 1988 Seoul Olympics after a positive test.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

What other drugs do athletes use?

Commonly used banned substances include HGH (human growth hormone), which helps build and repair muscle, and EPO (erythropoietin), which raises the red blood cell count and increases endurance and power. Athletes also use stimulants to reduce fatigue, and diuretics to mask the presence of other drugs. A more extreme technique — one that was employed by the disgraced seven-time Tour de France winner Lance Armstrong — is to have a blood transfusion before competing to increase endurance.

How do athletes escape detection?

They play an ongoing game of cat and mouse with anti-doping authorities. Anti-doping agencies are constantly trying to identify performance-enhancing drugs (PEDs) — and tests for them — while rogue scientists are always developing new ones. And while all athletes are subject to random testing at international events, the system is far from foolproof. Determined cheaters often find excuses to delay tests until banned substances leave their bodies. Several have been caught trying to smuggle in clean urine. Many employ doping experts who show them how to cycle on and off PEDs to reduce the chance of getting caught.

Can the system be improved?

One of the biggest developments in recent years was the 2009 introduction of the "Athlete Biological Passport." A constantly updated record of an athlete's physiological condition, including his or her red blood cell count and testosterone level, this electronic document is designed to detect the effects of banned substances rather than the drug itself. But athletes are getting around that by "microdosing" — taking steroids and EPO in smaller quantities, more regularly, rather than in big doses. The performance-enhancing benefits are subtler, but can still mean the difference between winning and losing. And microdosing drastically reduces the risk of being caught. "Microdosing can take an athlete from 10th place to first place," says Max Cobb, director of U.S. Biathlon. "But you're no longer seeing those extraordinary 'Oh, my God, how did that guy finish two minutes faster' moments." Anonymous athlete surveys suggest that from 14 to 39 percent of competitors still use PEDs, yet only 1 to 2 percent a year fail a drug test.

Doping in other sports

Almost every major sport has been hit with scandals related to performance-enhancing drugs. Steroid abuse was rampant in Major League Baseball in the 1990s and early 2000s, with players suddenly developing Popeye-size muscles and smashing home-run records. In cycling, nearly two-thirds of top-10 finishers in the Tour de France between 1998 and 2013 used performance-enhancing drugs. The NFL has had its own problems, with former NFL quarterback Brady Quinn saying that "40 to 50 percent" use PEDs. But pro football has been the least aggressive of major sports in testing players, with most taking just two or three tests a year — often with advance warning. In 2008, an investigative report by the San Diego Union-Tribune identified 185 NFL players as performance-enhancing drug users, spanning every position and every franchise. Yet none of the players was suspended, and the league did little to follow up. No one in the NFL has ever tested positive for HGH, despite accusations against several players, including two-time Super Bowl winner Peyton Manning. "The policy is completely inept," says Victor Conte, a convicted illegal supplement supplier. "If the NFL was interested in catching players who are doping, they wouldn't be doing the testing the way they are now."

-

Syria’s Kurds: abandoned by their US ally

Syria’s Kurds: abandoned by their US allyTalking Point Ahmed al-Sharaa’s lightning offensive against Syrian Kurdistan belies his promise to respect the country’s ethnic minorities

-

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?Talking Point Rambling speeches, wind turbine obsession, and an ‘unhinged’ letter to Norway’s prime minister have caused concern whether the rest of his term is ‘sustainable’

-

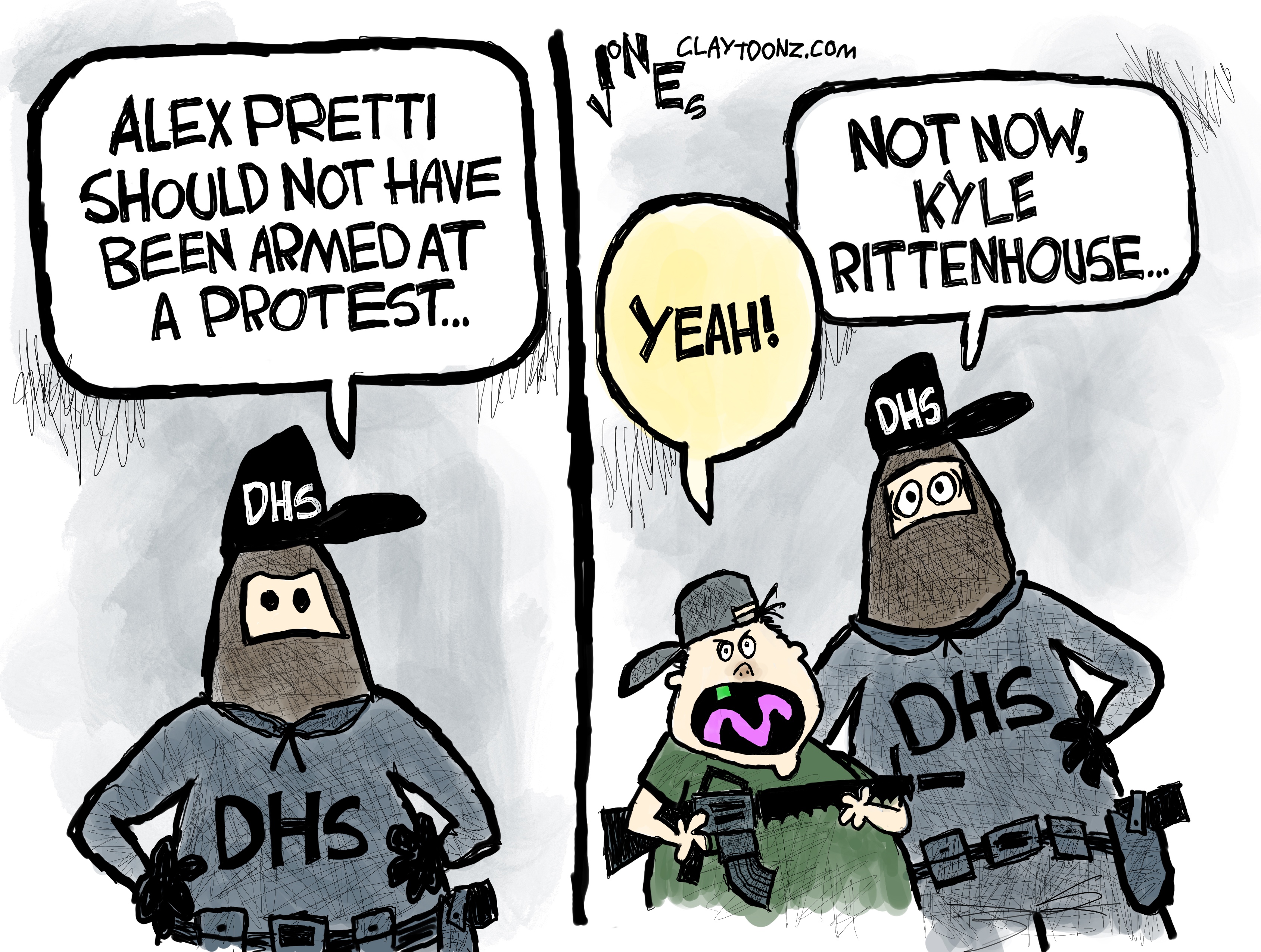

5 highly hypocritical cartoons about the Second Amendment

5 highly hypocritical cartoons about the Second AmendmentCartoons Artists take on Kyle Rittenhouse, the blame game, and more

-

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from Gaza

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from GazaSpeed Read The 24-year-old police officer was killed during the initial Hamas attack

-

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purge

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purgeSpeed Read Zhang Youxia is being investigated over ‘grave violations’ of the law

-

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mine

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mineIn the Spotlight Panama is set to make a final decision on the mine this summer

-

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mine

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mineThe Explainer The country’s natural landscape makes the task extremely difficult

-

Iran cuts internet as protests escalate

Iran cuts internet as protests escalateSpeed Reada Government buildings across the country have been set on fire

-

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by Russia

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by RussiaSpeed Read The ship was one of two vessels seized by the US military

-

How Bulgaria’s government fell amid mass protests

How Bulgaria’s government fell amid mass protestsThe Explainer The country’s prime minister resigned as part of the fallout

-

Femicide: Italy’s newest crime

Femicide: Italy’s newest crimeThe Explainer Landmark law to criminalise murder of a woman as an ‘act of hatred’ or ‘subjugation’ but critics say Italy is still deeply patriarchal